The Four Winds are a group of mythical figures in Mesopotamian mythology whose names and functions correspond to four cardinal directions of wind. They were both cardinal concepts (used for mapping and understanding geographical features in relation to each other) as well as characters with personality, who could serve as antagonistic forces or helpful assistants in myths.

The concept of the Four Winds originated in Sumer, before 3000 BCE. [1] While older theories posited that the ancient Mesopotamians had a concept of cardinality similar to modern day with a North, East, South, and West, it was more likely that their directions were framed around these four "principle winds". [1] The Akkadian word for cardinality is equivalent to the word for wind. [2] J. Neumann names these winds as "The regular wind" (NW), "The mountain wind" (NE), "The cloud wind" (SE), and "The Amorite Wind" (SW). [1] These wind directions could be used to establish the presence of astrological bodies, [1] orient maps, [1] and direct the layout of cities and home construction, keeping buildings open to wind blowing in and alleviating the heat. [1] These winds, aside from being used for cardinality, were also figures important to mythology and general culture in Mesopotamia.

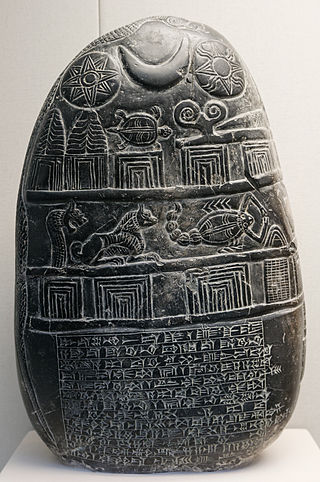

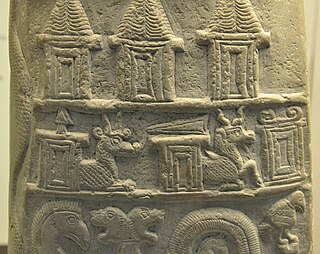

As figures, the four winds have been identified with four winged beings on cylinder seals. [3] Three are male (the NE, NW, and SW winds) and one (The South wind or South-East wind) is female. [3]

Franz Wiggermann also discusses an association between the winds (which he denotes as N, E, S, and W) and various constellations; Ursa Major as the North Wind, Pisces as the South Wind, Scorpio as the West wind, and the Pleiades as the East Wind. [3] Sometimes in incantation they are called upon as guardians, [3] in one particular text the South and East winds are singled out as being guarding winds. [3]

No clear genealogy is known for the winds, other than that they thought of as siblings. [3] They are affiliated with Anu in some texts, as his creations or his messengers. [3]

One Sumerian proverb describes them: "the North wind is the wind of satisfaction, the South wind overthrows the men it hits, the East wind is the wind that brings rain, and the West wind is mightier than the man living there." [3]

The name for this wind, referred to sometimes as the North wind in earlier scholarship, can mean "normal", "regular" or "favorable" wind. [4] This wind is likely what is called today as the Shamal, the most predictable wind in the Persian Gulf Region. [4] Most often portrayed as a good force, a gentle wind that is reliable. [3] Thought as having some connections to the goddess Ninlil, as well as Adad and Ninurta.

Usually translated simply as the East Wind, the etymology of the name is likely "mountain wind", or "direction of the mountains." [4] It is argued that this wind should be referred to as the North East wind, stemming from the direction of the wind blowing off of the Zagros mountain chain being centered around the North East. [5] This wind, in one ritual text, is referred to as a friend of the king Naram-Sin, [3] and is also speculated to be associated with Enlil. [3]

Usually translated as South wind, the name of this wind likely means "cloud wind." [4] This wind may correlate to a modern-day counterpart, the Kaus which blows around the South and East and is associated with the rain and thunderstorms of the wet season. [4] This wind is speculated to be feminine or female, as it is referred to with feminine pronouns in texts, and has been connected to the female winged figure on cylinder seals. [3] She also has a connection to the god Ea and was speculated to have taken on a more divine roll, gaining a horned crown of divinity and losing her wings in later depictions. [3] Sometimes this wind is characterized positively, but also had an evil aspect as a Demonic wind that needed to be chased away. [3]

Translated typically as the West wind, possibly denotes a stormy wind, [4] or a wind originating from the place where the sun sets. [4] The name "Amorite Wind" comes from the Assyrian-Babylonian term for this wind, "amurru", corresponding to the Amorite peoples who inhabited regions in the west and northwest relative to the Babylonian territory. [6] This wind is speculated to be associated with Anu. [3] There is little characterization of this wind in texts, leading to theories that the image of this wind was repurposed and evolved into the demon Pazuzu. [3]

In Enuma Elish, Marduk marshals the Four Winds to assist in trapping the monstrous Tiamat. [7] These winds were said to be given to him by Anu. [7] The text also describes him summoning and unleashing seven evil winds similar to those wielded by Ninurta in the Anzu Epic. [7] [8]

The South Wind appears in the myth of Adapa as an antagonistic force, preventing the sage from fishing in the sea and sinking his boat. [9] In response, Adapa breaks the Wind's wing, causing Anu to summon him to court when he realizes that the wind had stopped blowing. [10] Stephanie Dalley argues that the South Wind is female in the myth, with the other three winds as her brothers. [11]

In some versions of Gilgamesh, the winds are guides to the hero and his friend Enkidu, helping them navigate the cedar forest on the orders of Utu. [3]

The demon Pazuzu, who first appeared in the early Iron Age, [12] likely draws his iconography and much of his character from the Four Winds. He is also assigned the role of king over the lilu or wind demons as a category. [13]

Franz Wiggermann claims that due to iconographic links (a shared crouching posture), Pazuzu may have been derived specifically from the masculine West Wind. [3] There are also theories that Pazuzu possessing four wings represents his control over the totality of the wind demons. [2] In one myth, Pazuzu narrates ascending a mountain, where he encounters other winds and breaking their wings. [2]

Ancient Egyptian texts also have personifications of four winds, representing cardinal directions. [2] These winds have some iconographic links to their Mesopotamian counterparts (both groups processing wings) but they are described in the Coffin Texts and other rituals as having more chimera-like bodies with other animal parts. [2] In the Book of the Dead, they are said to come from different openings in the sky, [2] while in another myth, they were created when a divine falcon beat its wings. [2]

Humbaba, originally known as Ḫuwawa in Sumerian, was a figure in Mesopotamian mythology. The origin and meaning of his name are unknown. He was portrayed as an anthropomorphic figure comparable to an ogre or giant. He is best known from Sumerian and Akkadian narratives focused on the hero Gilgamesh, including short compositions belonging to the curriculum of scribal schools, various versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and several Hurrian and Hittite adaptations. He is invariably portrayed as the inhabitant or guardian of the cedar forest, to which Gilgamesh ventures with his companion Enkidu. The subsequent encounter leads to the death of Humbaba, which provokes the anger of the gods. Humbaba is also attested in other works of Mesopotamian literature. Multiple depictions of him have also been identified, including combat scenes and apotropaic clay heads.

In Mesopotamian mythology, Lamashtu was a female demon/monster/malevolent goddess or demigoddess who menaced women during childbirth and, if possible, kidnapped their children while they were breastfeeding. She would gnaw on their bones and suck their blood, and was charged with a number of other evil deeds. She was a daughter of the Sky God Anu.

In ancient Mesopotamian religion, Pazuzu is a personification of the southwestern wind, and held kingship over the lilu wind demons.

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology Hanbi or Hanpa was a member of the udug and he was the lord of evil, lord of all evil forces different from the gods and the father of Pazuzu. He was olso the creator of the solid monster Hunbaba and probably of the two solid creature named Asag and Anzu. The Udug were cabaple to enter inside the human body and they were born in the inferior realm. In a bilingual incantation written in both Sumerian and Akkadian, the god Asalluḫi describes the "evil udug" to his father Enki:

O my father, the evil udug [udug hul], its appearance is malignant and its stature towering, Although it is not a god (dingir) its clamour is great and its radiance [melam] immense, It is dark, its shadow is pitch black and there is no light within its body, It always hides, taking refuge, [it] does not stand proudly, Its claws drip with bile, it leaves poison in its wake, Its belt is not released, his arms enclose, It fills the target of his anger with tears, in all lands, [its] battle cry cannot be restrained.

The udug, later known in Akkadian as the utukku, were an ambiguous class of demons from ancient Mesopotamian mythology. They were different from the dingir and they were generally malicious, even if a member of demons (Pazuzu) was willing to clash both with other demons and with the gods, even if he is described as a presence hostile to humans. The word is generally ambiguous and is sometimes used to refer to demons as a whole rather than a specific kind of demon. No visual representations of the udug have yet been identified, but descriptions of it ascribe to it features often given to other ancient Mesopotamian demons: a dark shadow, absence of light surrounding it, poison, and a deafening voice. The surviving ancient Mesopotamian texts giving instructions for exorcizing the evil udug are known as the Udug Hul texts. These texts emphasize the evil udug's role in causing disease and the exorcist's role in curing the disease.

Enūma Eliš, meaning "When on High", is a Babylonian creation myth from the late 2nd millennium BCE and the only complete surviving account of ancient near eastern cosmology. It was recovered by English archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in 1849 in the ruined Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. A form of the myth was first published by English Assyriologist George Smith in 1876; active research and further excavations led to near completion of the texts and improved translation.

Anzû, also known as dZû and Imdugud, is a monster in several Mesopotamian religions. He was conceived by the pure waters of the Abzu and the wide Earth, or as son of Siris. Anzû was depicted as a massive bird who can breathe fire and water, although Anzû is alternately depicted as a lion-headed eagle.

Laḫmu is a class of apotropaic creatures from Mesopotamian mythology. While the name has its origin in a Semitic language, Lahmu was present in Sumerian sources in pre-Sargonic times already.

Ancient Semitic religion encompasses the polytheistic religions of the Semitic peoples from the ancient Near East and Northeast Africa. Since the term Semitic itself represents a rough category when referring to cultures, as opposed to languages, the definitive bounds of the term "ancient Semitic religion" are only approximate, but exclude the religions of "non-Semitic" speakers of the region such as Egyptians, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni, Urartians, Luwians, Minoans, Greeks, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Medes, Philistines and Parthians.

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a city-state located east of the Tigris, in the proximity of the borders of Elam. It is known that he was a divine judge, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period in royal inscriptions and theophoric names. He appears in sources from the reign of many later dynasties as well. When Der attained independence after the Ur III period, local rulers were considered representatives of Ištaran. In later times, he retained his position in Der, and multiple times his statue was carried away by Assyrians to secure the loyalty of the population of the city.

Ningishzida was a Mesopotamian deity of vegetation, the underworld and sometimes war. He was commonly associated with snakes. Like Dumuzi, he was believed to spend a part of the year in the land of the dead. He also shared many of his functions with his father Ninazu.

Lulal, inscribed dlú.làl in cuneiform(𒀭𒇽𒋭), was a Mesopotamian god associated with Inanna, usually as a servant deity or bodyguard but in a single text as a son. His name has Sumerian origin and can be translated as "syrup man."

Ilabrat was a Mesopotamian god who in some cases was regarded as the sukkal of the sky god Anu. Evidence from the Old Assyrian period indicates that he could also be worshiped as an independent deity.

Kakka was a Mesopotamian deity. She was originally worshiped across Upper Mesopotamia as a healing goddess, but later on came to be secondarily viewed as a male messenger god in Babylonia. Kakka's oldest attested cult center is Maškan-šarrum, located in the south of Assyria, though she was also worshiped in the kingdom of Mari, especially in Terqa. She appears in numerous theophoric names from this area, with Akkadian, Amorite and Hurrian examples attested. As early as in the Old Babylonian period she could be associated with Ninshubur, and later on with Papsukkal as well. However, she developed connection with Ninkarrak, Išḫara and possibly Nisaba as well. The male form of Kakka appears as a messenger of Anu in the Sultantepe version of the myth Nergal and Ereshkigal, and as a messenger of Anshar in Enūma Eliš.

The Sebitti or Sebittu are a group of seven minor war gods in Neo-Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and especially Assyrian tradition. They also appear in sources from Emar. Multiple different interpretations of the term occur in Mesopotamian literature.

Anu or Anum, originally An, was the divine personification of the sky, king of the gods, and ancestor of many of the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. He was regarded as a source of both divine and human kingship, and opens the enumerations of deities in many Mesopotamian texts. At the same time, his role was largely passive, and he was not commonly worshipped. It is sometimes proposed that the Eanna temple located in Uruk originally belonged to him, rather than Inanna, but while he is well attested as one of its divine inhabitants, there is no evidence that the main deity of the temple ever changed, and Inanna was already associated with it in the earliest sources. After it declined, a new theological system developed in the same city under Seleucid rule, resulting in Anu being redefined as an active deity. As a result he was actively worshipped by inhabitants of the city in the final centuries of the history of ancient Mesopotamia.

Ušumgallu or Ushumgallu was one of the three horned snakes in Akkadian mythology, along with the Bašmu and Mušmaḫḫū. Usually described as a lion-dragon demon, it has been somewhat speculatively identified with the four-legged, winged dragon of the late 3rd millennium BCE.

Mesopotamian mythology refers to the myths, religious texts, and other literature that comes from the region of ancient Mesopotamia which is a historical region of Western Asia, situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system that occupies the area of present-day Iraq. In particular the societies of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria, all of which existed shortly after 3000 BCE and were mostly gone by 400 CE. These works were primarily preserved on stone or clay tablets and were written in cuneiform by scribes. Several lengthy pieces have survived erosion and time, some of which are considered the oldest stories in the world, and have given historians insight into Mesopotamian ideology and cosmology.

The ancient Mesopotamian underworld, was the lowermost part of the ancient near eastern cosmos, roughly parallel to the region known as Tartarus from early Greek cosmology. It was described as a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground, where inhabitants were believed to continue "a transpositional version of life on earth". The only food or drink was dry dust, but family members of the deceased would pour sacred mineral libations from the earth for them to drink. In the Sumerian underworld, it was initially believed that there was no final judgement of the deceased and the dead were neither punished nor rewarded for their deeds in life.

Ardat-lilî was a Mesopotamian demon. She is described as the ghost of a young woman who died without experiencing sexual fulfillment or getting married, and as a result attempts to seduce young men. She is one of the members of the category of lil demons, who were considered subjects of Pazuzu. A text placing her in the entourage of the god Erra is also known. Incantations directed against her are attested as early as in the Old Babylonian period. References to her are also known from other genres of texts.