Related Research Articles

Helen Adams Keller was an American author, disability rights advocate, political activist and lecturer. Born in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, she lost her sight and her hearing after a bout of illness when she was 19 months old. She then communicated primarily using home signs until the age of seven, when she met her first teacher and life-long companion Anne Sullivan. Sullivan taught Keller language, including reading and writing. After an education at both specialist and mainstream schools, Keller attended Radcliffe College of Harvard University and became the first deafblind person in the United States to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree.

Anne Sullivan Macy was an American teacher best known for being the instructor and lifelong companion of Helen Keller.

Perkins School for the Blind, in Watertown, Massachusetts, was founded in 1829 and is the oldest school for the blind in the United States. It has also been known as the Perkins Institution for the Blind.

Jack Frost is a personification of frost, ice, snow, sleet, winter, and freezing cold. He is a variant of Old Man Winter who is held responsible for frosty weather, nipping the fingers and toes in such weather, coloring the foliage in autumn, and leaving fern-like patterns on cold windows in winter.

Laura Dewey Lynn Bridgman was the first deaf-blind American child to gain a significant education in the English language, twenty years before the more famous Helen Keller; Laura's friend Anne Sullivan became Helen Keller's aide. Bridgman was left deaf-blind at the age of two after contracting scarlet fever. She was educated at the Perkins Institution for the Blind where, under the direction of Samuel Gridley Howe, she learned to read and communicate using Braille and the manual alphabet developed by Charles-Michel de l'Épée.

Cryptomnesia occurs when a forgotten memory returns without its being recognized as such by the subject, who believes it is something new and original. It is a memory bias whereby a person may falsely recall generating a thought, an idea, a tune, a name, or a joke; they are not deliberately engaging in plagiarism, but are experiencing a memory as if it were a new inspiration.

Helen Keller: The Miracle Continues is a 1984 American made-for-television biographical film and a semi-sequel to the 1979 television version of The Miracle Worker. It is a drama based on the life of the blind and deaf Helen Keller and premiered in syndication on April 23, 1984, as part of Operation Prime Time syndicated programming.

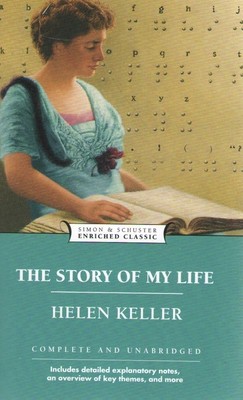

The Story of My Life, first published in book form in 1903, is Helen Keller's autobiography detailing her early life, particularly her experiences with Anne Sullivan. Portions of it were adapted by William Gibson for a 1957 Playhouse 90 production, a 1959 Broadway play, a 1962 Hollywood feature film, and the Indian film Black. The book is dedicated to inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who was one of her teachers and an advocate for the deaf.

Ragnhild Tollefsen Kåta was the first deafblind person in Norway who received proper schooling. Despite being deafblind, she learned to talk. The story of her success was an inspiration to Helen Keller.

The Miracle Worker is a 1962 American biographical film about Anne Sullivan, blind tutor to Helen Keller, directed by Arthur Penn. The screenplay by William Gibson is based on his 1959 play of the same title, which originated as a 1957 broadcast of the television anthology series Playhouse 90. Gibson's secondary source material was The Story of My Life, the 1903 autobiography of Helen Keller.

The Story of Esther Costello is a 1957 British drama film starring Joan Crawford and co-starring Rossano Brazzi, and Heather Sears. The film is a story of large-scale fundraising. The Story of Esther Costello was produced by David Miller and Jack Clayton, with Miller directing. The screenplay by Charles Kaufman was based on the 1952 novel by Nicholas Monsarrat. It was distributed by Columbia Pictures.

The Miracle Worker is a three-act play by William Gibson adapted from his 1957 Playhouse 90 teleplay of the same name. It was based on Helen Keller's 1903 autobiography The Story of My Life.

Elsie Leslie was an American actress. She was America's first child star and the highest paid and most popular child actress of her era.

The Miracle Worker is a 2000 American made-for-television biographical film based on the 1959 play of the same title by William Gibson, which originated as a 1957 broadcast of the television anthology series Playhouse 90. Gibson's original source material was The Story of My Life, the 1903 autobiography of Helen Keller. The play was adapted for the screen twice before, in 1962 and 1979. The film is based on the life of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan's struggles to teach her. The film premiered on ABC as part of The Wonderful World of Disney on November 12, 2000.

The Miracle Worker is a 1979 American made-for-television biographical film based on the 1959 play of the same title by William Gibson, which originated as a 1957 broadcast of the television anthology series Playhouse 90. Gibson's original source material was The Story of My Life, the 1903 autobiography of Helen Keller. The play was adapted for the screen before, in 1962.

Helen Keller Day is a commemorative holiday to celebrate the birth of Helen Keller, observed on June 27 annually. The holiday observance was created by presidential proclamation in 2006, as well as by international organizations, particularly those helping the blind and the deaf. The holiday is generally known for its fashion show held on June 27 annually for fundraising purposes.

Joseph Edgar "J. E." or "Ed" Chamberlin was an American journalist, columnist, essayist, and editor whose work appeared in newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York, as well as in national magazines and journals, beginning in 1871 and continuing until his death in 1935. Beginning in the late 1880s, he wrote a popular column for the Boston Evening Transcript called "The Listener" and thus became known throughout New England as "The Listener of the Transcript." He was a friend and mentor to many aspiring writers, photographers, musicians, and artists, and maintained a close friendship with Helen Keller and her teacher Anne Sullivan for over 40 years. He died in South Hanson, Massachusetts in 1935 and is buried in his birthplace of Newbury, Vermont.

Michael Anagnos was a trustee and later second director of the Perkins School for the Blind. He was an author, educator, and human rights activist. Anagnos is well known for his work with Helen Keller.

Julia Romana Howe Anagnos was an American poet, daughter of Samuel Gridley Howe and Julia Ward Howe.

Thomas Stringer was an American carpenter. Deafblind from a young age, Stringer was brought to the Perkins Institution for the Blind through the fundraising of Helen Keller. He was well-regarded at the school for his carpentry skills, which he used to help support himself after graduating from Perkins in 1913.

References

- What Helen Saw, New Yorker article discussing Helen's life and accusations of plagiarism and coaching throughout her life.