Henry Fielding was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling was a seminal work in the genre. Along with Samuel Richardson, Fielding is seen as the founder of the traditional English novel. He also played an important role in the history of law enforcement in the United Kingdom, using his authority as a magistrate to found the Bow Street Runners, London's first professional police force.

John Hervey, 2nd Baron Hervey, was an English courtier and political writer. Heir to the Earl of Bristol, he obtained the key patronage of Walpole, and was involved in many court intrigues and literary quarrels, being apparently caricatured by Pope and Fielding. His memoirs of the early reign of George II were too revealing to be published in his time and did not appear for more than a century.

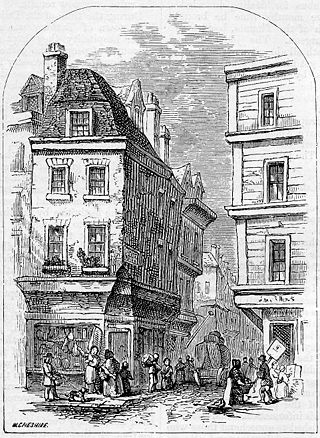

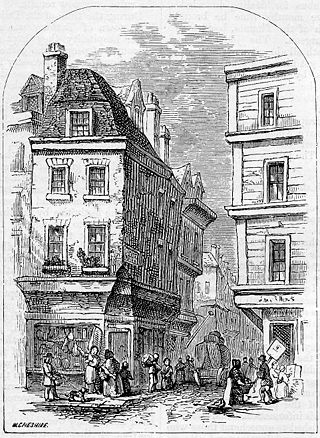

Until the early 19th century, Grub Street was a street close to London's impoverished Moorfields district that ran from Fore Street east of St Giles-without-Cripplegate north to Chiswell Street. It was pierced along its length with narrow entrances to alleys and courts, many of which retained the names of early signboards. Its bohemian society was set amidst the impoverished neighbourhood's low-rent dosshouses, brothels and coffeehouses.

Augustan literature is a style of British literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II in the first half of the 18th century and ending in the 1740s, with the deaths of Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift, in 1744 and 1745, respectively. It was a literary epoch that featured the rapid development of the novel, an explosion in satire, the mutation of drama from political satire into melodrama and an evolution toward poetry of personal exploration. In philosophy, it was an age increasingly dominated by empiricism, while in the writings of political economy, it marked the evolution of mercantilism as a formal philosophy, the development of capitalism and the triumph of trade.

The Historical Register for the Year 1736 is a 1737 play by Henry Fielding. A denunciation of contemporary society and politics, most notably prime minister Sir Robert Walpole, it was performed for the first time in April 1737 and published shortly thereafter by J. Roberts in London according to the book's title page.

Augustan drama can refer to the dramas of Ancient Rome during the reign of Caesar Augustus, but it most commonly refers to the plays of Great Britain in the early 18th century, a subset of 18th-century Augustan literature. King George I referred to himself as "Augustus," and the poets of the era took this reference as apropos, as the literature of Rome during Augustus moved from historical and didactic poetry to the poetry of highly finished and sophisticated epics and satire.

James Ralph was an American-born English political writer, historian, reviewer, and Grub Street hack writer known for his works of history and his position in Alexander Pope's Dunciad B. His History of England in two volumes (1744–46) and The Case of the Authors by Profession of 1758 became the dominant narratives of their time.

The early plays of Henry Fielding mark the beginning of Fielding's literary career. His early plays span the time period from his first production in 1728 to the beginning of the Actor's Rebellion of 1733, a strife within the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane that divided the theatrical community and threatened to disrupt London stage performances. These plays introduce Fielding's take on politics, gender, and morality and serve as an early basis for how Fielding develops his ideas on these matters throughout his career.

Love in Several Masques is a play by Henry Fielding that was first performed on 16 February 1728 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The moderately received play comically depicts three lovers trying to pursue their individual beloveds. The beloveds require their lovers to meet their various demands, which serves as a means for Fielding to introduce his personal feelings on morality and virtue. In addition, Fielding introduces criticism of women and society in general.

The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town is a play by the English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding, first performed on 30 March 1730 at the Little Theatre, Haymarket. Written in response to the Theatre Royal's rejection of his earlier plays, The Author's Farce was Fielding's first theatrical success. The Little Theatre allowed Fielding the freedom to experiment, and to alter the traditional comedy genre. The play ran during the early 1730s and was altered for its run starting 21 April 1730 and again in response to the Actor Rebellion of 1733. Throughout its life, the play was coupled with several different plays, including The Cheats of Scapin and Fielding's Tom Thumb.

The Tragedy of Tragedies, also known as The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great, is a play by Henry Fielding. It is an expanded and reworked version of one of his earlier plays, Tom Thumb, and tells the story of a character who is small in stature and status, yet is granted the hand of a princess in marriage; the infuriated queen and another member of the court subsequently attempt to destroy the marriage.

The Welsh Opera is a play by Henry Fielding. First performed on 22 April 1731 in Haymarket, the play replaced The Letter Writers and became the companion piece to The Tragedy of Tragedies. It was also later expanded into The Grub-Street Opera. The play's purported author is Scriblerus Secundus who is also a character in the play. This play is about Secundus' role in writing two (Fielding) plays: The Tragedy of Tragedies and The Welsh Opera.

The Grub Street Opera is a play by Henry Fielding that originated as an expanded version of his play The Welsh Opera. It was never put on for an audience and is Fielding's single print-only play. As in The Welsh Opera, the author of the play is identified as Scriblerus Secundus. Secundus also appears in the play and speaks of his role in composing the plays. In The Grub Street Opera the main storyline involves two men and their rival pursuit of women.

The Old Debauchees, originally titled The Despairing Debauchee, was a play written by Henry Fielding. It originally appeared with The Covent-Garden Tragedy on 1 June 1732 at the Royal Theatre, Drury Lane and was later revived as The Debauchees; or, The Jesuit Caught. The play tells the story of Catholic priest's attempt to manipulate a man to seduce the man's daughter, ultimately unsuccessfully.

The Covent-Garden Tragedy is a play by Henry Fielding that first appeared on 1 June 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane alongside The Old Debauchees. It is about a love triangle in a brothel involving two prostitutes. While they are portrayed satirically, they are imbued with sympathy as their relationship develops.

The Mock Doctor: or The Dumb Lady Cur'd is a play by Henry Fielding and first ran on 23 June 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. It served as a replacement for The Covent-Garden Tragedy and became the companion play to The Old Debauchees. It tells the exploits of a man who pretends to be a doctor at his wife's requests.

The Actor Rebellion of 1733 was an event that took place at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London, England, when the actors who worked there, disapproving of the changes in the management, attempted to seize control. Before the rebellion, the theatre was controlled by the managers Theophilus Cibber, John Ellys, and John Highmore. When Theophilus lost his share and was denied a bid to run the theatre, he, along with other actors, attempted to take over the theatre by controlling the lease. When the shareholders found out, they refused to admit the actors to the building and the theatre was closed for several months. The fight spilled over to the contemporary newspapers, which generally sided with the managers.

The Life and Death of the Late Jonathan Wild, the Great is a satiric novel by Henry Fielding. It was published in 1743 in Fielding's Miscellanies, third volume. It is a satiric account of the life of London underworld boss Jonathan Wild (1682–1725). It is an experiment in the various narrative genres that were popular at the time: serious history, criminal biography, political satire, and picaresque novel. Some have argued that it is mainly a satire on Britain's first Prime Minister Robert Walpole, who was continuously charged by his political enemies with allegations of corruption.

Fatal Curiosity is a 1737 tragedy by the British writer George Lillo. It is also known by the alternative title Guilt Its Own Punishment.

Thomas Odell was an English playwright, and for a short time producer of plays at a theatre he erected, Goodman's Fields Theatre.