The Pinnacles are limestone formations within Nambung National Park, near the town of Cervantes, Western Australia. [1]

The Pinnacles are limestone formations within Nambung National Park, near the town of Cervantes, Western Australia. [1]

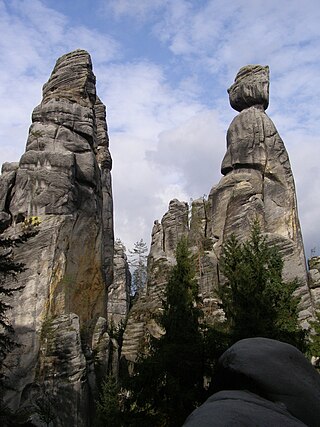

The area contains thousands of weathered limestone pillars. Some of the tallest pinnacles reach heights of up to 3.5 m above the yellow sand base. The different types of formations include ones which are much taller than they are wide and resemble columns—suggesting the name of Pinnacles—while others are only a metre or so in height and width resembling short tombstones. A cross-bedding structure can be observed in many pinnacles where the angle of deposited sand changed suddenly due to changes in prevailing winds during formation of the limestone beds. Pinnacles with tops similar to mushrooms are created when the calcrete capping is harder than the limestone layer below it. The relatively softer lower layers weather and erode at a faster rate than the top layer leaving behind more material at the top of the pinnacle. [2]

The raw material for the limestone of the Pinnacles came from seashells in an earlier era that was rich in marine life. These shells were broken down into lime-rich sands that were blown inland to form high mobile dunes. [3] However, the manner in which such raw materials formed the Pinnacles is the subject of debate. Three major theories have been proposed:

The first theory states that they were formed as dissolutional remnants of the Tamala Limestone, i.e. that they formed as a result of a period of extensive solutional weathering (karstification). Focused solution initially formed small solutional depressions, mainly solution pipes, which were progressively enlarged over time, resulting in the pinnacle topography. Some pinnacles represent cemented void infills (microbialites and/or re-deposited sand), which are more resistant to erosion, but dissolution still played the final role in pinnacle development. [3] [4]

A second theory states that they were formed through the preservation of tree casts buried in coastal aeolianites, where roots became groundwater conduits, resulting in the precipitation of indurated (hard) calcrete. Subsequent wind erosion of the aeolianite then exposed the calcrete pillars. [5]

A third proposal suggests that plants played an active role in the creation of the Pinnacles, based on the mechanism that formed smaller "root casts" in other parts of the world. As transpiration drew water through the soil to the roots, nutrients and other dissolved minerals flowed toward the root—a process termed "mass-flow" that can result in the accumulation of nutrients at the surface of the root, if the nutrients arrive in quantities greater than that needed for plant growth. In coastal aeolian sands that consist of large amounts of calcium (derived from marine shells), the movement of water to the roots would drive the flow of calcium to the root surface. This calcium accumulates at high concentrations around the roots and over time is converted into a calcrete. When the roots die, the space occupied by the root is subsequently also filled with a carbonate material derived from the calcium in the former tissue of the roots, and possibly also from water leaching through the structures. Although evidence has been provided for this mechanism in the formation of root casts in South Africa, evidence is still required for its role in the formation of the Pinnacles. [6]

Western grey kangaroos graze on the vegetation in the park, usually in the early morning. The kangaroos are considered quite tame, sometimes allowing quiet, slow-moving visitors to approach them. Baudin's black cockatoos and emus are frequently observed in the park. Reptiles such as bobtails, sand goannas and carpet pythons are a few of the other park inhabitants. [7]

Some of the common plant species include panjang (a low-lying wattle), coastal wattle and banjine, quandong, yellow tailflower, thick-leaved fanflower and cockies tongues. Parrot bush, candlestick banksia, firewood banksia and acorn banksia are also common in the park. [7]

The Pinnacles remained unknown to most Australians until 1967 when the area was gazetted as a reserve, which was later combined with two adjacent reserves to form Nambung National Park in 1994. [8]

Nambung National Park received about 150,000 visitors a year as of 2011. [7] The Pinnacles Desert Discovery Centre was opened in 2008, offering interpretive displays of the park, both the natural processes that formed the Pinnacles and the biodiversity of the area. [7]

The best season to visit the Pinnacles is in the months of August to October, as the days are mild and wildflowers, along with wattle, begin to bloom in the spring. [1]

No lodging or camping areas are available within Nambung National Park but accommodations can be found in Cervantes. [1]

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat regions covered with wind-swept sand or dunes, with little or no vegetation, are called ergs or sand seas. Dunes occur in different shapes and sizes, but most kinds of dunes are longer on the stoss (upflow) side, where the sand is pushed up the dune, and have a shorter slip face in the lee side. The valley or trough between dunes is called a dune slack.

A stalactite is a mineral formation that hangs from the ceiling of caves, hot springs, or man-made structures such as bridges and mines. Any material that is soluble and that can be deposited as a colloid, or is in suspension, or is capable of being melted, may form a stalactite. Stalactites may be composed of lava, minerals, mud, peat, pitch, sand, sinter, and amberat. A stalactite is not necessarily a speleothem, though speleothems are the most common form of stalactite because of the abundance of limestone caves.

Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park is a national park in the South West region of Western Australia, 267 km (166 mi) south of Perth. It is named after the two locations at either end of the park which have lighthouses, Cape Leeuwin and Cape Naturaliste. It is located in the Augusta-Margaret River and Busselton council areas, and is claimed to have the highest visiting numbers of any national park in Western Australia. The park received 2.33 million visitors through 2008–2009.

Nambung National Park is a national park in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia, 200 km northwest of Perth, Australia and 17 km south of the small coastal town of Cervantes. The park contains the Pinnacles Desert which is an area with thousands of limestone formations called pinnacles.

Caliche is a soil accumulation of soluble calcium carbonate at depth, where it precipitates and binds other materials—such as gravel, sand, clay, and silt. It occurs worldwide, in aridisol and mollisol soil orders—generally in arid or semiarid regions, including in central and western Australia, in the Kalahari Desert, in the High Plains of the western United States, in the Sonoran Desert, Chihuahuan Desert and Mojave Desert of North America, and in eastern Saudi Arabia at Al-Hasa. Caliche is also known as calcrete or kankar. It belongs to the duricrusts. The term caliche is borrowed from Spanish and is originally from the Latin word calx, meaning lime.

Gypcrete or gypcrust is a hardened layer of soil, consisting of around 95% gypsum. Gypcrust is an arid zone duricrust. It can also occur in a semiarid climate in a basin with internal drainage, and is initially developed in a playa as an evaporate. Gypcrete is the arid climate's equivalent to calcrete, which is a duricrust that is unable to generate in very arid climates.

Mount Eliza is a hill that overlooks the city of Perth, Western Australia and forms part of Kings Park. It is known as Kaarta Gar-up and Mooro Katta in the local Noongar dialect.

Banksia aemula, commonly known as the wallum banksia, is a shrub of the family Proteaceae. Found from Bundaberg south to Sydney on the Australian east coast, it is encountered as a shrub or a tree to 8 m (26 ft) in coastal heath on deep sandy soil, known as Wallum. It has wrinkled orange bark and shiny green serrated leaves, with green-yellow flower spikes, known as inflorescences, appearing in autumn. The flower spikes turn grey as they age and large grey follicles appear. Banksia aemula resprouts from its woody base, known as a lignotuber, after bushfires.

Banksia prionotes, commonly known as acorn banksia or orange banksia, is a species of shrub or tree of the genus Banksia in the family Proteaceae. It is native to the southwest of Western Australia and can reach up to 10 m (33 ft) in height. It can be much smaller in more exposed areas or in the north of its range. This species has serrated, dull green leaves and large, bright flower spikes, initially white before opening to a bright orange. Its common name arises from the partly opened inflorescence, which is shaped like an acorn. The tree is a popular garden plant and also of importance to the cut flower industry.

Tamala Limestone is the geological name given to the widely occurring eolianite limestone deposits on the western coastline of Western Australia, between Shark Bay in the north and nearly to Albany in the south. The rock consists of calcarenite wind-blown shell fragments and quartz sand which accumulated as coastal sand dunes during the middle and late Pleistocene and early Holocene eras. As a result of a process of sedimentation and water percolating through the shelly sands, the mixture later lithified when the lime content dissolved to cement the grains together.

The Zuytdorp Cliffs extend for about 150 km (93 mi) along a rugged, spectacular and little visited segment of the Western Australian Indian Ocean coast. The cliffs extend from just south of the mouth of the Murchison River at Kalbarri, to Pepper Point south of Steep Point. The cliffs are situated in both the Gascoyne and Mid West regions of the state.

Eucalyptus botryoides, commonly known as the bangalay, bastard jarrah, woollybutt or southern mahogany, is a small to tall tree native to southeastern Australia. Reaching up to 40 metres high, it has rough bark on its trunk and branches. It is found on sandstone- or shale-based soils in open woodland, or on more sandy soils behind sand dunes. The white flowers appear in summer and autumn. It reproduces by resprouting from its woody lignotuber or epicormic buds after bushfire. E. botryoides hybridises with the Sydney blue gum in the Sydney region. The hard, durable wood has been used for panelling and flooring.

Eolianite or aeolianite is any rock formed by the lithification of sediment deposited by aeolian processes; that is, the wind. In common use, however, the term refers specifically to the most common form of eolianite: coastal limestone consisting of carbonate sediment of shallow marine biogenic origin, formed into coastal dunes by the wind, and subsequently lithified. It is also known as kurkar in the Middle East, miliolite in India and Arabia, and grès dunaire in the eastern Mediterranean. eolianite has a hardness of 4.3 and is very dull. Streak is light brown.

The Nambung River is a river in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia, 170 kilometres (106 mi) north of Perth. The river drains an area between the towns of Cervantes and Badgingarra. In its lower reaches the Nambung River forms a chain of waterholes in the Nambung Wetlands where it disappears underground into a limestone karst system 5.5 kilometres (3 mi) from the Indian Ocean.

A pinnacle, tower, spire, needle or natural tower in geology is an individual column of rock, isolated from other rocks or groups of rocks, in the shape of a vertical shaft or spire. is a natural geomorphological shape and a structural denudation shape of the relief. It is about an isolated, tall and often also slender column or prism, reminiscent of a tower in its shape. A specific type of rock tower is the rock needle.

Southern Beekeeper's Nature Reserve is a nature reserve in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia, approximately 240 kilometres (149 mi) north of Perth. It is one of 90 nature reserves operated in the Department of Parks and Wildlife's Moora District. Access to much of the reserve is provided by Indian Ocean Drive. Information sites at Southern Beekeeper's include the Molah Hill vista point and Hill River.

Bangham Conservation Park is a protected area in the Australian state of South Australia located in the state's Limestone Coast in the gazetted locality of Bangham about 45 kilometres (28 mi) north-east of the town centre in Naracoorte.

The Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub, which also incorporates Sydney Coastal Heaths, is a remnant sclerophyll scrubland and heathland that is found in the eastern and southern regions of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 as and endangered vegetation community and as 'critically endangered' under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub is found on ancient, nutrient poor sands either on dunes or on promontories. Sydney coastal heaths are a scrubby heathland found on exposed coastal sandstone plateau in the south.

The Banksia Woodlands of the Swan Coastal Plain is a protected sclerophyll community situated in the Swan Coastal Plain, Western Australia that predominantly consists of banksias. Listed as endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, it was once a near-incessant band of large shrub patches around Perth and other nearby coastal areas.

{{cite book}}: |work= ignored (help) (photography, Alan Stephens - text, Sue Hughes)