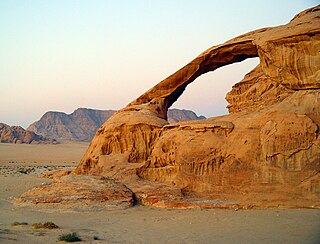

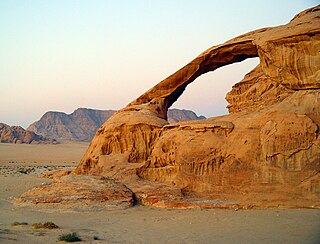

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals through contact with water, atmospheric gases, sunlight, and biological organisms. It occurs in situ, and so is distinct from erosion, which involves the transport of rocks and minerals by agents such as water, ice, snow, wind, waves and gravity.

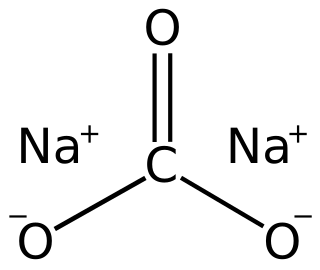

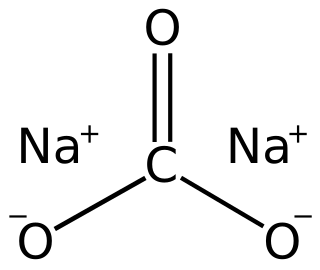

Sodium carbonate is the inorganic compound with the formula Na2CO3 and its various hydrates. All forms are white, odourless, water-soluble salts that yield alkaline solutions in water. Historically, it was extracted from the ashes of plants grown in sodium-rich soils, and because the ashes of these sodium-rich plants were noticeably different from ashes of wood, sodium carbonate became known as "soda ash". It is produced in large quantities from sodium chloride and limestone by the Solvay process, as well as by carbonating sodium hydroxide which is made using the chloralkali process.

Sodium nitrate is the chemical compound with the formula NaNO

3. This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Chile saltpeter to distinguish it from ordinary saltpeter, potassium nitrate. The mineral form is also known as nitratine, nitratite or soda niter.

Travertine is a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs, especially hot springs. It often has a fibrous or concentric appearance and exists in white, tan, cream-colored, and rusty varieties. It is formed by a process of rapid precipitation of calcium carbonate, often at the mouth of a hot spring or in a limestone cave. In the latter, it can form stalactites, stalagmites, and other speleothems. It is frequently used in Italy and elsewhere as a building material. Similar deposits formed from ambient-temperature water are known as tufa.

A dry lake bed, also known as a playa, is a basin or depression that formerly contained a standing surface water body, which disappears when evaporation processes exceed recharge. If the floor of a dry lake is covered by deposits of alkaline compounds, it is known as an alkali flat. If covered with salt, it is known as a salt flat.

Niter or nitre is the mineral form of potassium nitrate, KNO3. It is a soft, white, highly soluble mineral found primarily in arid climates or cave deposits.

Duricrust is a hard layer on or near the surface of soil. Duricrusts can range in thickness from a few millimeters or centimeters to several meters.

The pedosphere is the outermost layer of the Earth that is composed of soil and subject to soil formation processes. It exists at the interface of the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere and biosphere. The pedosphere is the skin of the Earth and only develops when there is a dynamic interaction between the atmosphere, biosphere, lithosphere and the hydrosphere. The pedosphere is the foundation of terrestrial life on Earth.

In soil science, agriculture and gardening, hardpan or soil pan is a dense layer of soil, usually found below the uppermost topsoil layer. There are different types of hardpan, all sharing the general characteristic of being a distinct soil layer that is largely impervious to water. Some hardpans are formed by deposits in the soil that fuse and bind the soil particles. These deposits can range from dissolved silica to matrices formed from iron oxides and calcium carbonate. Others are man-made, such as hardpan formed by compaction from repeated plowing, particularly with moldboard plows, or by heavy traffic or pollution.

Water softening is the removal of calcium, magnesium, and certain other metal cations in hard water. The resulting soft water requires less soap for the same cleaning effort, as soap is not wasted bonding with calcium ions. Soft water also extends the lifetime of plumbing by reducing or eliminating scale build-up in pipes and fittings. Water softening is usually achieved using lime softening or ion-exchange resins, but is increasingly being accomplished using nanofiltration or reverse osmosis membranes.

A soil horizon is a layer parallel to the soil surface whose physical, chemical and biological characteristics differ from the layers above and beneath. Horizons are defined in many cases by obvious physical features, mainly colour and texture. These may be described both in absolute terms and in terms relative to the surrounding material, i.e. 'coarser' or 'sandier' than the horizons above and below.

The Pinnacles are limestone formations within Nambung National Park, near the town of Cervantes, Western Australia.

Gypcrete or gypcrust is a hardened layer of soil, consisting of around 95% gypsum. Gypcrust is an arid zone duricrust. It can also occur in a semiarid climate in a basin with internal drainage, and is initially developed in a playa as an evaporate. Gypcrete is the arid climate's equivalent to calcrete, which is a duricrust that is unable to generate in very arid climates.

Calcareous is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

A sabkha is a coastal, supratidal mudflat or sandflat in which evaporite-saline minerals accumulate as the result of semiarid to arid climate. Sabkhas are gradational between land and intertidal zone within restricted coastal plains just above normal high-tide level. Within a sabkha, evaporite-saline minerals sediments typically accumulate below the surface of mudflats or sandflats. Evaporite-saline minerals, tidal-flood, and aeolian deposits characterize many sabkhas found along modern coastlines. The accepted type locality for a sabkha is at the southern coast of the Persian Gulf, in the United Arab Emirates. Evidence of clastic sabkhas are found in the geological record of many areas, including the UK and Ireland. Sabkha is a phonetic transliteration of the Arabic word used to describe any form of salt flat. A sabkha is also known as a sabkhah,sebkha, or coastal sabkha.

Alkaline precipitation occurs due to natural and anthropogenic causes. It happens when minerals, such as calcium, aluminum, or magnesium combine with other minerals to form alkaline residues that are emitted into the atmosphere, absorbed by water droplets in clouds, and eventually fall as rain. Aquatic environments are especially impacted by alkaline precipitation. Because alkaline precipitation can be harmful to the environment, it is important to utilize various methods such as air pollution control, solidification and stabilization, and remediation to manage it.

Alkali, or Alkaline, soils are clay soils with high pH, a poor soil structure and a low infiltration capacity. Often they have a hard calcareous layer at 0.5 to 1 metre depth. Alkali soils owe their unfavorable physico-chemical properties mainly to the dominating presence of sodium carbonate, which causes the soil to swell and difficult to clarify/settle. They derive their name from the alkali metal group of elements, to which sodium belongs, and which can induce basicity. Sometimes these soils are also referred to as alkaline sodic soils. Alkaline soils are basic, but not all basic soils are alkaline.

Kankar or (kunkur) is a sedimentological term derived from Hindi which is occasionally applied in both India and the United States to detrital or residual rolled, often nodular calcium carbonate formed in soils of semi-arid regions. It is used in the making of lime and of roads. It forms sheets across alluvial plains, and can occur as discontinuous lines of nodular kankar or as indurated layers in stratigraphic profiles. Such are more generally referred to as calcrete, hardpan or duricrust.

Microspherulites are microscopic spherical particles with diameter less than two mm, usually in the 100 micrometre range, mainly consisting of mineral material. Only bodies created by natural physico-chemical processes, with no contribution of either biological or human activity, are considered to be microspherulites. Generally speaking, the common feature (sphericity) indicates that each sphere represents an internal equilibrium of forces within a fluid medium.

The Blanco Formation, originally named the Blanco Canyon Beds, is an early Pleistocene geologic formation of clay, sand, and gravel whitened by calcium carbonate cementation and is recognized in Texas and Kansas.