Related Research Articles

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, drywall and blackboard or sidewalk chalk. Gypsum also crystallizes as translucent crystals of selenite. It forms as an evaporite mineral and as a hydration product of anhydrite. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness defines gypsum as hardness value 2 based on scratch hardness comparison.

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with groundwater, which may be fresh, saline, or brackish, depending on the locality. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated.

An evaporite is a water-soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as ocean deposits, and non-marine, which are found in standing bodies of water such as lakes. Evaporites are considered sedimentary rocks and are formed by chemical sediments.

A concretion is a hard, compact mass formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular shapes also occur. The word 'concretion' is derived from the Latin concretio "(act of) compacting, condensing, congealing, uniting", itself from con meaning 'together' and crescere meaning "to grow". Concretions form within layers of sedimentary strata that have already been deposited. They usually form early in the burial history of the sediment, before the rest of the sediment is hardened into rock. This concretionary cement often makes the concretion harder and more resistant to weathering than the host stratum.

Aridisols are a soil order in USDA soil taxonomy. Aridisols form in an arid or semi-arid climate. Aridisols dominate the deserts and xeric shrublands, which occupy about one third of the Earth's land surface. Aridisols have a very low concentration of organic matter, reflecting the paucity of vegetative production on these dry soils. Water deficiency is the major defining characteristic of Aridisols. Also required is sufficient age to exhibit subsoil weathering and development. Limited leaching in aridisols often results in one or more subsurface soil horizons in which suspended or dissolved minerals have been deposited: silicate clays, sodium, calcium carbonate, gypsum or soluble salts. These subsoil horizons can also be cemented by carbonates, gypsum or silica. Accumulation of salts on the surface can result in salinization.

In geology, a chott, shott, or shatt is a salt lake in Africa's Maghreb that stays dry for much of the year but receives some water in the winter. The elevation of a chott surface is controlled by the position of the water table and capillary fringe, with sediment deflation occurring when the water table falls and sediment accumulation occurring when the water table rises. They are formed—within variable shores—by the spring thaw from the Atlas mountain range, along with occasional rainwater or groundwater sources in the Sahara, such as the Bas Saharan Basin.

Duricrust is a hard layer on or near the surface of soil. Duricrusts can range in thickness from a few millimeters or centimeters to several meters.

Dolomite (also known as dolomite rock, dolostone or dolomitic rock) is a sedimentary carbonate rock that contains a high percentage of the mineral dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2. It occurs widely, often in association with limestone and evaporites, though it is less abundant than limestone and rare in Cenozoic rock beds (beds less than about 66 million years in age). The first geologist to distinguish dolomite from limestone was Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu; a French mineralogist and geologist whom it is named after. He recognized and described the distinct characteristics of dolomite in the late 18th century, differentiating it from limestone.

A soil horizon is a layer parallel to the soil surface whose physical, chemical and biological characteristics differ from the layers above and beneath. Horizons are defined in many cases by obvious physical features, mainly colour and texture. These may be described both in absolute terms and in terms relative to the surrounding material, i.e. 'coarser' or 'sandier' than the horizons above and below.

Caliche is a sedimentary rock, a hardened natural cement of calcium carbonate that binds other materials—such as gravel, sand, clay, and silt. It occurs worldwide, in aridisol and mollisol soil orders—generally in arid or semiarid regions, including in central and western Australia, in the Kalahari Desert, in the High Plains of the western United States, in the Sonoran Desert, Chihuahuan Desert and Mojave Desert of North America, and in eastern Saudi Arabia at Al-Hasa. Caliche is also known as calcrete or kankar. It belongs to the duricrusts. The term caliche is borrowed from Spanish and is originally from the Latin word calx, meaning lime.

The vadose zone, also termed the unsaturated zone, is the part of Earth between the land surface and the top of the phreatic zone, the position at which the groundwater is at atmospheric pressure. Hence, the vadose zone extends from the top of the ground surface to the water table.

Fossil water or paleowater is an ancient body of water that has been contained in some undisturbed space, typically groundwater in an aquifer, for millennia. Other types of fossil water can include subglacial lakes, such as Antarctica's Lake Vostok, and even ancient water on other planets.

A sabkha is a coastal, supratidal mudflat or sandflat in which evaporite-saline minerals accumulate as the result of semiarid to arid climate. Sabkhas are gradational between land and intertidal zone within restricted coastal plains just above normal high-tide level. Within a sabkha, evaporite-saline minerals sediments typically accumulate below the surface of mudflats or sandflats. Evaporite-saline minerals, tidal-flood, and aeolian deposits characterize many sabkhas found along modern coastlines. The accepted type locality for a sabkha is at the southern coast of the Persian Gulf, in the United Arab Emirates. Evidence of clastic sabkhas are found in the geological record of many areas, including the UK and Ireland. Sabkha is a phonetic transliteration of the Arabic word used to describe any form of salt flat. A sabkha is also known as a sabkhah,sebkha, or coastal sabkha.

A petrocalcic horizon is a diagnostic horizon in the USDA soil taxonomy (ST) and in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB). They are formed when secondary Calcium Carbonate or other carbonates accumulate in the subsoil to the extent that the soil becomes cemented into a hardpan. Petrocalcic horizons are similar to a duripan and a petrogypsic horizon (WRB) in how they affect land-use limitations. They can occur in conjunction with duripans where the conditions are right and there are enough free carbonates in the soil. Calcium Carbonates are found in alkaline soils, which are typical of arid and semiarid climates. A common field test for the presence of carbonates is application of hydrochloric acid to the soil, which indicates by fizzing and bubbling the presence of calcium carbonates.

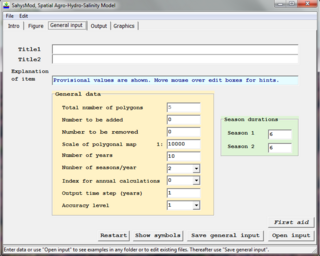

SahysMod is a computer program for the prediction of the salinity of soil moisture, groundwater and drainage water, the depth of the watertable, and the drain discharge in irrigated agricultural lands, using different hydrogeologic and aquifer conditions, varying water management options, including the use of ground water for irrigation, and several crop rotation schedules, whereby the spatial variations are accounted for through a network of polygons.

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the land surface of the Earth is arid or semi-arid. This includes much of the polar regions, where little precipitation occurs, and which are sometimes called polar deserts or "cold deserts". Deserts can be classified by the amount of precipitation that falls, by the temperature that prevails, by the causes of desertification or by their geographical location.

The Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle is also referred to as MC-19. The Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle covers the area from 0° to 45° west longitude and 0° to 30° south latitude on Mars. Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle contains Margaritifer Terra and parts of Xanthe Terra, Noachis Terra, Arabia Terra, and Meridiani Planum.

Laterite is a soil type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by intensive and prolonged weathering of the underlying parent rock, usually when there are conditions of high temperatures and heavy rainfall with alternate wet and dry periods. The process of formation is called laterization. Tropical weathering is a prolonged process of chemical weathering which produces a wide variety in the thickness, grade, chemistry and ore mineralogy of the resulting soils. The majority of the land area containing laterites is between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

DPHM-RS is a semi-distributed hydrologic model developed at University of Alberta, Canada.

Rain and snow was a regular occurrence on Mars in the past; especially in the Noachian and early Hesperian epochs. Some moisture entered the ground and formed aquifers. That is, the water went into the ground, seeped down until it reached a formation that would not allow it to penetrate further. Water then accumulated forming a saturated layer. Deep aquifers may still exist.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Walker, M.J. (2012). Hot Deserts: Engineering, Geology and Geomorphology: Engineering Group Working Day Report. Geological Society of London. ISBN 9781862393424 . Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- 1 2 Britannica, Encyclopedia. "gypcrete". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Fred G. (4 January 2002). Geological Hazards: Their Assessment, Avoidance and Mitigation. Taylor & Francis, 2002. ISBN 9780203014660 . Retrieved 7 October 2013.