Related Research Articles

The Scorpaeniformes are a diverse order of ray-finned fish, including the lionfishes and sculpins, but have also been called the Scleroparei. It is one of the five largest orders of bony fishes by number of species, with over 1,320.

Myliobatiformes is one of the four orders of batoids, cartilaginous fishes related to sharks. They were formerly included in the order Rajiformes, but more recent phylogenetic studies have shown the myliobatiforms to be a monophyletic group, and its more derived members evolved their highly flattened shapes independently of the skates.

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to support an unbroken herbaceous layer consisting primarily of grasses.There exists four savanna forms; savanna woodland where trees and shrubs form a light canopy, tree savanna with scattered trees and shrubs, shrub savanna with distributed shrubs, and grass savanna where trees and shrubs are mostly nonexistent.

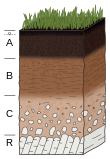

A soil type is a taxonomic unit in soil science. All soils that share a certain set of well-defined properties form a distinctive soil type. Soil type is a technical term of soil classification, the science that deals with the systematic categorization of soils. Every soil of the world belongs to a certain soil type. Soil type is an abstract term. In nature, you will not find soil types. You will find soils that belong to a certain soil type.

USDA soil taxonomy (ST) developed by the United States Department of Agriculture and the National Cooperative Soil Survey provides an elaborate classification of soil types according to several parameters and in several levels: Order, Suborder, Great Group, Subgroup, Family, and Series. The classification was originally developed by Guy Donald Smith, former director of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's soil survey investigations.

The Darling Downs is a farming region on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range in southern Queensland, Australia. The Downs are to the west of South East Queensland and are one of the major regions of Queensland. The name was generally applied to an area approximating to that of the Condamine River catchment upstream of Condamine township but is now applied to a wider region comprising the Southern Downs, Western Downs, Toowoomba and Goondiwindi local authority areas. The name Darling Downs was given in 1827 by Allan Cunningham, the first European explorer to reach the area and recognises the then Governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling.

Soil classification deals with the systematic categorization of soils based on distinguishing characteristics as well as criteria that dictate choices in use.

In soil science, podzols, also known as podosols, spodosols, or espodossolos, are the typical soils of coniferous or boreal forests and also the typical soils of eucalypt forests and heathlands in southern Australia. In Western Europe, podzols develop on heathland, which is often a construct of human interference through grazing and burning. In some British moorlands with podzolic soils, cambisols are preserved under Bronze Age barrows.

A vertisol is a Soil Order in the USDA soil taxonomy and a Reference Soil Group in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB). It is also defined in many other soil classification systems. In the Australian Soil Classification it is called vertosol. Vertisols have a high content of expansive clay minerals, many of them belonging to the montmorillonites that form deep cracks in drier seasons or years. In a phenomenon known as argillipedoturbation, alternate shrinking and swelling causes self-ploughing, where the soil material consistently mixes itself, causing some vertisols to have an extremely deep A horizon and no B horizon.. This heaving of the underlying material to the surface often creates a microrelief known as gilgai.

Ceratopetalum apetalum, the coachwood, scented satinwood or tarwood, is a medium-sized hardwood tree, straight-growing with smooth, fragrant, greyish bark. It is native to eastern Australia in the central and northern coastal rainforests of New South Wales and southern Queensland, where is often found on poorer quality soils in gullies and creeks and often occurs in almost pure stands. C. apetalum is one of 8 species of Ceratopetalum occurring in eastern Australia, New Guinea, New Britain and various islands in the same region.

Diplacodes haematodes, the scarlet percher, is a species of dragonfly in the family Libellulidae. It occurs throughout Australia, Timor, New Guinea, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia. It is locally common in habitats with hot sunny exposed sites at or near rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes. It often prefers to settle on hot rocks rather than twigs or leaves, and is quite wary. This is a spectacular species of dragonfly, although small in size. The male is brilliant red, the female yellow-ochre. Females have yellow infuscation suffusing the outer wings, while the males have similar colour at the bases of the wings.

Acid sulfate soils are naturally occurring soils, sediments or organic substrates that are formed under waterlogged conditions. These soils contain iron sulfide minerals and/or their oxidation products. In an undisturbed state below the water table, acid sulfate soils are benign. However, if the soils are drained, excavated or otherwise exposed to air, the sulfides react with oxygen to form sulfuric acid.

The Canadian System of Soil Classification is more closely related to the American system than any other, but they differ in several ways. The Canadian system is designed to cover only Canadian soils. The Canadian system dispenses with the sub-order hierarchical level. Solonetzic and Gleysolic soils are differentiated at the order level.

The black-backed butcherbird is a species of bird in the family Artamidae. It is found in southern New Guinea and Cape York Peninsula in Queensland, Australia.

The Northcote Football Club (/ˈnoːθ.kət/), nicknamed the Dragons, was an Australian rules football club which played in the VFA from 1908 until 1987. The club's colours for most of its time in the VFA were green and yellow, and it was based in the Melbourne suburb of Northcote.

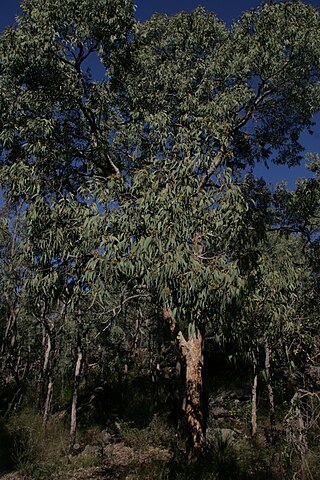

Corymbia eximia, commonly known as yellow bloodwood, is a bloodwood native to New South Wales. It occurs around the Sydney Basin often in high rainfall areas on shallow sandstone soils on plateaux or escarpments, in fire prone areas. Growing as a gnarled tree to 20 m (66 ft), it is recognisable by its distinctive yellow-brown tessellated bark. The greyish green leaves are thick and veiny, and lanceolate spear- or sickle-shaped. The cream flowerheads grow in panicles in groups of seven and appear in spring. Known for many years as Eucalyptus eximia, the yellow bloodwood was transferred into the new genus Corymbia in 1995 when it was erected by Ken Hill and Lawrie Johnson. It is still seen under the earlier name in some works.

The term "duplex" is used in Australia for soils with contrasting texture between soil horizons, although such soils are found in other parts of the world. Duplex soils are also termed "texture contrast soils".

BurmannialesMart. was an order of monocotyledons, subsequently discontinued.

The Eyre Basin beaked gecko is a gecko endemic to Australia in the family Diplodactylidae. It is found throughout parts of South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory and New South Wales.

Atriplex angulata, commonly known as fan saltbush or angular saltbush, is a species of flowering plant in the family Amaranthaceae. It is an annual to short-lived perennial subshrub, native to Australia, distributed throughout drier parts of the mainland.

References

- ↑ "Australian Soil Classification (as Online Key)". CSIRO. March 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Isbell, Raymond F. (1996). The Australian Soil Classification (1st ed.). Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-643-05813-3.

- ↑ Isbell, Raymond F. (2002). The Australian Soil Classification (Revised ed.). Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-643-06898-8.

- ↑ CSIRO. "How to Classify". The Australian Soil Classification. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ The National Committee on Soil and Terrain (2 June 2021). "The Australian Soil Classification". Soil Science Australia. Archived from the original on 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- 1 2 Northcote, Keith H. (1960). A factual key for the recognition of Australian soils. Divisional Report No. 4/60. CSIRO Division of Soils.

- ↑ Northcote, Keith H. (1971). A factual key for the recognition of Australian soils (3rd ed.). Glenside, South Australia: Rellim Technical Publications.

- ↑ Stace, H.C.T.; Hubble, G.D.; Brewer, R; Northcote, K.H.; Sleeman, J.R.; Mulcahy, M.J.; Hallsworth, E.G. (1968). A Handbook of Australian Soils. Glenside, South Australia: Rellim Technical Publications.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, R.W.; Powell, B.; McKenzie, N.J.; Maschmedt, D.J.; Schoknecht, N. (2003). "Demands on soil classification in Australia". In Eswaran, H.; Rice, T.; Ahrens, R.; Stewart, B.A. (eds.). Soil Classification: A Global Desk Reference. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-1339-2.

- ↑ CSIRO. "Colour Classes". The Australian Soil Classification. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ CSIRO. "Hydrosols". The Australian Soil Classification. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ CSIRO. "Rudosols". The Australian Soil Classification. Retrieved 14 July 2010.