Related Research Articles

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix was a German painter and printmaker, noted for his ruthless and harshly realistic depictions of German society during the Weimar Republic and the brutality of war. Along with George Grosz and Max Beckmann, he is widely considered one of the most important artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit.

Julius Mordecai Pincas, known as Pascin, Jules Pascin, also known as the "Prince of Montparnasse", was a Bulgarian artist of the School of Paris, known for his paintings and drawings. He later became an American citizen. His most frequent subject was women, depicted in casual poses, usually nude or partly dressed.

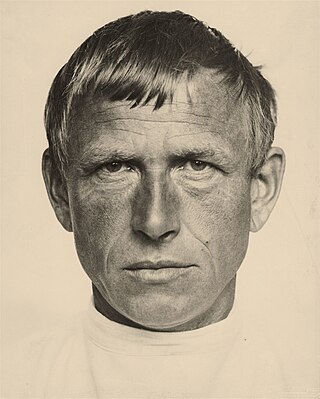

George Grosz was a German artist known especially for his caricatural drawings and paintings of Berlin life in the 1920s. He was a prominent member of the Berlin Dada and New Objectivity groups during the Weimar Republic. He emigrated to the United States in 1933, and became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Abandoning the style and subject matter of his earlier work, he exhibited regularly and taught for many years at the Art Students League of New York. In 1959 he returned to Berlin, where he died shortly afterwards.

The New Objectivity was a movement in German art that arose during the 1920s as a reaction against expressionism. The term was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the Kunsthalle in Mannheim, who used it as the title of an art exhibition staged in 1925 to showcase artists who were working in a post-expressionist spirit. As these artists—who included Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter and Jeanne Mammen—rejected the self-involvement and romantic longings of the expressionists, Weimar intellectuals in general made a call to arms for public collaboration, engagement, and rejection of romantic idealism.

Joachim Ringelnatz is the pen name of the German author and painter Hans Bötticher (7 August 1883, Wurzen, Saxony – 17 November 1934, Berlin). From 1894 to 1900 he lived with his family in the Gottschedstrasse 40 in Leipzig.

Paul Nash was a British surrealist painter and war artist, as well as a photographer, writer and designer of applied art. Nash was among the most important landscape artists of the first half of the twentieth century. He played a key role in the development of Modernism in English art.

Adolph Stephan Friedrich Jentsch was a German-born Namibian artist. He studied at the Dresden Staatsakademie für Bildende Künste for six years, and used a travel grant award to visit France, Italy, UK and the Netherlands. Jentsch moved to Namibia in 1938 to escape the approaching war and lived there until his death. He travelled extensively in Namibia and eventually settled down near Dordabis, about 60 km from the capital Windhoek. He is one of Namibia's most famous painters.

Karl Hubbuch was a German painter, printmaker, and draftsman associated with the New Objectivity.

James Edward Buchanan Boswell was a New Zealand-born British painter, draughtsman and socialist.

The Memorial Art Gallery is a civic art museum in Rochester, New York. Founded in 1913, it is part of the University of Rochester and occupies the southern half of the University's former Prince Street campus. It is a focal point of fine arts activity in the region and hosts the biennial Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition and the annual Clothesline Festival.

Fit for Active Service is a drawing by 20th-century German artist George Grosz, created between 1916 and 1917. It is considered a seminal part of the post-World War I movement, Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. The medium is pen, brush, and ink on paper.

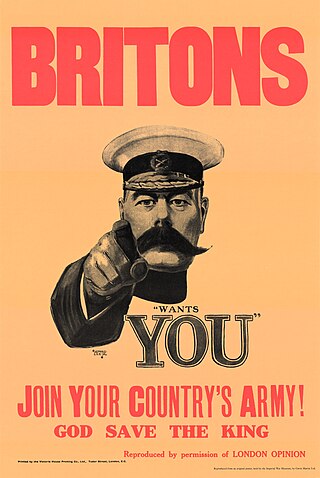

The First World War, which was fought between 1914 and 1918, had an immediate impact on popular culture. In the over a hundred years since the war ended, the war has resulted in many artistic and cultural works from all sides and nations that participated in the war. This included artworks, books, poems, films, television, music, and more recently, video games. Many of these pieces were created by soldiers who took part in the war.

Adrian Keith Graham Hill was a British artist, writer, art therapist, educator and broadcaster. Hill served with the Honourable Artillery Company during World War I and was the first artist commissioned by the Imperial War Museum to record the conflict on the Western Front. He wrote many books about painting and drawing, and in the 1950s and early 1960s presented a BBC children's television programme called Sketch Club.

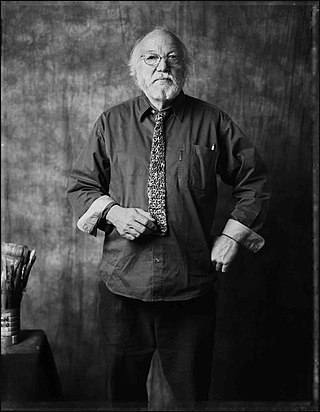

Robert P. Cenedella, Jr. is an American artist. He became well known for several of his paintings, including commissions by Bacardi, Heinz, Absolut Vodka and Le Cirque.

Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890 is an oil-on-canvas painting by French Neo-impressionist artist Paul Signac, created in 1890. The work depicts the French art critic Félix Fénéon standing in front of a swirling, kaleidoscope background. The painting's bold approach—utilizing color, pattern, and brushstroke to blend representation with abstraction—highlights a pivotal moment in Neo-Impressionism's history, influenced by the close bond between the artist and the critic. This piece is not just an iconic portrayal of Fénéon, but also acts as a visual declaration for Neo-Impressionism, grounded in nineteenth-century color theory, and signals the onset of modernism. It has been in Museum of Modern Art in New York since 1991, having been donated by Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller.

Lord Ribblesdale, sometimes known as The Ancestor, is a portrait in oils on canvas by John Singer Sargent of Thomas Lister, 4th Baron Ribblesdale, completed in 1902. The full-length portrait depicts Lord Ribblesdale in his hunting clothes. It measures 258.4 cm × 143.5 cm and has been held by the National Gallery in London since 1916.

Eclipse of the Sun is an oil-on-canvas painting by German artist George Grosz, painted in 1926. It is held at the Heckscher Museum of Art, in Huntington, New York, where it is the most famous painting.

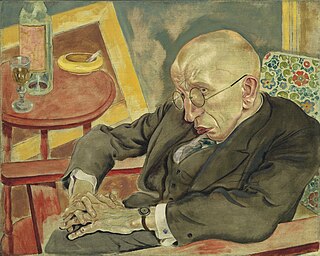

The Poet Max Hermann-Neisse is an oil-on-canvas painting executed in 1927 by German artist George Grosz. It depicts his personal friend, the writer and cabaret critic Max Herrmann-Neisse. The portrait is exemplary of the New Objectivity artistic approach. It is held at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York.

Cain, or Hitler in Hell is an oil-on-canvas painting by German American artist George Grosz, painted in 1944. It is one of the most known paintings of the years when Grosz lived in the United States, from 1933 to 1959, after leaving Germany, shortly after the Nazis seized power. It was part of Grosz's heirs collection until being purchased in 2019 by the Deutsches Historisches Museum, in Berlin, where it has been exhibited since 2020.

The Love Sick is an oil on canvas painting by the German expressionist painter George Grosz, executed in 1916. The unsigned work is held at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, in Düsseldorf. It was bought from the New York gallery owner Richard L. Feigen, in 1979.

References

- ↑ "Memorial Art Gallery". magart.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-10.

- 1 2 "MAG Collection - The Wanderer". magart.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-10.

- ↑ Jentsch, Ralph (2008). George Grosz (1st ed.). Milano, Italy: Skira Editore. pp. 25 and 221. ISBN 9788861302945.

- ↑ Searl, Marjorie; Norwood, Nancy (2006). Seeing America: Painting and Sculpture from the Collection of the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester (PDF). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 9781580462464.

- ↑ Grosz, George; Berenson, Ruth; Muhlen, Norbert (1960). Bittner, Herbert (ed.). George Grosz (1st ed.). 667 Madison Avenue, New York: Arts, Inc. pp. 81–82.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Jentsch, Ralph (2008). George Grosz (1st ed.). Milano, Italy: Skira Editore. p. 210. ISBN 9788861302945.

- ↑ Grosz, George (1983). George Grosz: An Autobiography. Translated by Hodges, Nora. New York: Macmillian Publishing Company. p. 97.

- 1 2 Grosz, George (1946). A Little Yes and a Big No; The Autobiography of George Grosz. Translated by Dorin, Lola. New York: The Dial Press. p. 301.

- 1 2 Grosz, George; Berenson, Ruth; Muhlen, Norbert (1960). Bittner, Herbert (ed.). George Grosz (1st ed.). 667 Madison Avenue, New York: Arts, Inc. p. 32.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)