Related Research Articles

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States, among whom it is traditionally the primary governmental institution, legislative body, and economic system. This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Coast Salish cultures. Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, although mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, also known as the Kwakiutl, are one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their current population, according to a 2016 census, is 3,665. Most live in their traditional territory on northern Vancouver Island, nearby smaller islands including the Discovery Islands, and the adjacent British Columbia mainland. Some also live outside their homelands in urban areas such as Victoria and Vancouver. They are politically organized into 13 band governments.

The Snohomish people are a Lushootseed-speaking Southern Coast Salish people who are indigenous to the Puget Sound region of Washington State. Most Snohomish are enrolled in the Tulalip Tribes of Washington and reside on the reservation or nearby, although others are enrolled in other tribes, and some are members of the non-recognized Snohomish Tribe of Indians. Traditionally, the Snohomish occupied a wide area of land, including the Snohomish River, parts of Whidbey and Camano Islands, and the nearby coastline of Skagit Bay and Puget Sound. They had at least 25 permanent villages throughout their lands, but in 1855, signed the Treaty of Point Elliott and were relocated to the Tulalip Reservation. Although some moved to the reservation, the harsh conditions, lack of land, and oppressive policies of the United States government caused many to leave.

Haisla people are a First Nation who reside in Kitamaat. The Haisla consist of two bands: the Kitamaat people, residing in upper Douglas Channel and Devastation Channel, and the Kitlope People, inhabiting upper Princess Royal Channel and Gardner Canal in British Columbia, Canada.

Twana is the collective name for a group of nine Coast Salish peoples in the northern-mid Puget Sound region. The Skokomish are the main surviving group and self-identify as the Twana today. The spoken language, also named Twana, is part of the Central Coast Salish language group. The Twana language is closely related to Lushootseed.

Prehistoric Alaska begins with Paleolithic people moving into northwestern North America sometime between 40,000 and 15,000 years ago across the Bering Land Bridge in western Alaska; a date less than 20,000 years ago is most likely. They found their passage blocked by a huge sheet of ice until a temporary recession in the Wisconsin glaciation opened up an ice-free corridor through northwestern Canada, possibly allowing bands to fan out throughout the rest of the continent. Eventually, Alaska became populated by the Inuit and a variety of Native American groups. Trade with both Asia and southern tribes was active even before the advent of Europeans.

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast are composed of many nations and tribal affiliations, each with distinctive cultural and political identities. They share certain beliefs, traditions and practices, such as the centrality of salmon as a resource and spiritual symbol, and many cultivation and subsistence practices. The term Northwest Coast or North West Coast is used in anthropology to refer to the groups of Indigenous people residing along the coast of what is now called British Columbia, Washington State, parts of Alaska, Oregon, and Northern California. The term Pacific Northwest is largely used in the American context.

The word dentalium, as commonly used by Native American artists and anthropologists, refers to tooth shells or tusk shells used in indigenous jewelry, adornment, and commerce in western Canada and the United States. These tusk shells are a kind of seashell, specifically the shells of scaphopod mollusks. The name "dentalium" is based on the scientific name for the genus Dentalium, but because the taxonomy has changed over time, not all of the species used are still placed in that genus; however, all of the species are certainly in the family Dentaliidae.

A button blanket is wool blanket embellished with mother-of-pearl buttons, created by Northwest Coastal tribes, that is worn for ceremonial purposes.

The culture of the Tlingit, an Indigenous people from Alaska, British Columbia, and the Yukon, is multifaceted, a characteristic of Northwest Coast peoples with access to easily exploited rich resources. In Tlingit culture a heavy emphasis is placed upon family and kinship, and on a rich tradition of oratory. Wealth and economic power are important indicators of status, but so is generosity and proper behavior, all signs of "good breeding" and ties to aristocracy. Art and spirituality are incorporated in nearly all areas of Tlingit culture, with even everyday objects such as spoons and storage boxes decorated and imbued with spiritual power and historical associations.

Nalukataq is the spring whaling festival of the Iñupiat of Northern Alaska, especially the North Slope Borough. It is characterized by its namesake, the dramatic Eskimo blanket toss. "Marking the end of the spring whaling season," Nalukataq creates "a sense of being for the entire community and for all who want a little muktuk or to take part in the blanket toss....At no time, however, does Nalukataq relinquish its original purpose, which is to recognize the annual success and prowess of each umialik, or whaling crew captain....Nalukataq [traditions] have always reflected the process of survival inherent in sharing...crucial to...the Arctic."

Squamish culture is the customs, arts, music, lifestyle, food, painting and sculpture, moral systems and social institutions of the Squamish indigenous people, located in the southwestern part of British Columbia, Canada. They refer to themselves as Sḵwx̱wú7mesh. They are a part of the Coast Salish cultural group. Their culture and social life is based on the abundant natural resource of the Pacific Northwest coast, rich in cedar trees, salmon, and other resources. They have complex kinship ties that connect their social life and cultural events to different families and neighboring nations.

The Xhosa people, or Xhosa-speaking people are a Bantu ethnic group native to South Africa. They are the second largest ethnic group in South Africa and are native speakers of the isiXhosa language.

Salish are skilled weavers and knitters of the Pacific Northwest. They are most noted for their beautiful twill blankets many of which are very old. The adoption of new fabrics, dyes, and weaving techniques allow us to study a wide variety of Salish weavings today.

Kwakwaka'wakw art describes the art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples of British Columbia. It encompasses a wide variety of woodcarving, sculpture, painting, weaving and dance. Kwakwaka'wakw arts are exemplified in totem poles, masks, wooden carvings, jewelry and woven blankets. Visual arts are defined by simplicity, realism, and artistic emphasis. Dances are observed in the many rituals and ceremonies in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. Much of what is known about Kwakwaka'wakw art comes from oral history, archeological finds in the 19th century, inherited objects, and devoted artists educated in Kwakwaka'wakw traditions.

The potlatch ban was legislation forbidding the practice of the potlatch passed by the Government of Canada, begun in 1885 and lasting until 1951.

'Kwakwaka'wakw music is a sacred and ancient art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples that has been practiced for thousands of years. The Kwakwaka'wakw are a collective of twenty-five nations of the Wakashan language family who altogether form part of a larger identity comprising the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, located in what is known today as British Columbia, Canada.

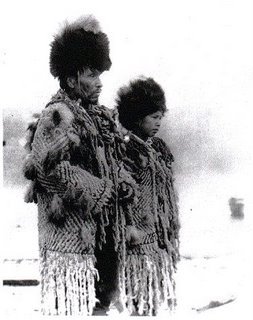

The Tanana Athabaskans, Tanana Athabascans, or Tanana Athapaskans are an Alaskan Athabaskan people from the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group. They are the original inhabitants of the Tanana River drainage basin in east-central Alaska Interior, United States and a little part lived in Yukon, Canada. Tanana River Athabaskan peoples are called in Lower Tanana and Koyukon language Ten Hʉt'ænæ, in Gwich'in language Tanan Gwich'in. In Alaska, where they are the oldest, there are three or four groups identified by the languages they speak. These are the Tanana proper or Lower Tanana and/or Middle Tanana, Tanacross or Tanana Crossing, and Upper Tanana. The Tanana Athabaskan culture is a hunter-gatherer culture with a matrilineal system. Tanana Athabaskans were semi-nomadic and lived in semi-permanent settlements in the Tanana Valley lowlands. Traditional Athabaskan land use includes fall hunting of moose, caribou, Dall sheep, and small terrestrial animals, as well as trapping. The Athabaskans did not have any formal tribal organization. Tanana Athabaskans were strictly territorial and used hunting and gathering practices in their semi-nomadic way of life and dispersed habitation patterns. Each small band of 20–40 people normally had a central winter camp with several seasonal hunting and fishing camps, and they moved cyclically, depending on the season and availability of resources.

Alaskan ice cream is a dessert made by Alaskan Athabaskans and other Alaska Natives.

A traditional Swazi wedding ceremony is called umtsimba, where the bride commits herself to her new family for the rest of her life. The ceremony is a celebration that includes members of both the bride's - and the groom's - natal village. There are stages to the wedding that stretch over a few days. Each stage is significant, comprising symbolic gestures that have been passed on from generation to generation. The first stage is the preparation of the bridal party before leaving their village. The second stage is the actual journey of the bridal party from their village to the groom's village. The third stage is the first day of the wedding ceremony that spans three days, and starts on the day the bridal party arrives at the grooms’ village. Thereafter the actual wedding ceremony takes place which is the fourth stage of the umtsimba. The fifth stage takes place the day after the wedding ceremony and is known as kuteka, which is the actual wedding. The final stage may take place the day after the wedding day, and is when the bride gives the groom's family gifts and is the first evening the bride spends with the groom. Although the traditional wedding ceremony has evolved in modern times, the details below are based on historic accounts of anthropologist Hilda Kuper and sociological research describing the tradition

References

- 1 2 Laurence A. Goldin, The Land is Ours, 1996, Auroroa Films

- 1 2 William Simeone, A History of Alaskan Athapaskans, 1982, Alaska Historical Commission

- 1 2 A.E. Stephan, The First Athabascans of Alaska:Strawberries, 1996, Dorrance Publishing, ISBN 0-8059-3883-4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 William Simeone, Rifles, Blankets, and Beads, 1995, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2713-9

- ↑ Simeone, Identity 183

- ↑ Simeone, Identity 210

- ↑ Thomas Mishler, Crow is my Boss: the oral history of a Tanacross Athabaskan elder, University of Oklahoma Press, 2005

- ↑ Poldine Carlo, Nulato: An Indian Life on the Yukon, Fairbanks, Alaska, 1978

- ↑ file:///home/chronos/u-15985fe980d04ec3ec881e482cd33c8a6e32a755/Downloads/fulltext.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 Claire Fejes, Villagers: Athabaskan Indian Life Along the Yukon River, Random House, 1981, ISBN 0-394-51673-7