A gift economy or gift culture is a system of exchange where valuables are not sold, but rather given without an explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards. Social norms and customs govern giving a gift in a gift culture; although there is some expectation of reciprocity, gifts are not given in an explicit exchange of goods or services for money, or some other commodity or service. This contrasts with a barter economy or a market economy, where goods and services are primarily explicitly exchanged for value received.

Marshall David Sahlins was an American cultural anthropologist best known for his ethnographic work in the Pacific and for his contributions to anthropological theory. He was the Charles F. Grey Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and of Social Sciences at the University of Chicago.

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in economic anthropology focus on exchange.

Marcel Mauss was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic, sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology. His most famous work is The Gift (1925).

Social exchange theory is a sociological and psychological theory that studies the social behavior in the interaction of two parties that implement a cost-benefit analysis to determine risks and benefits. The theory also involves economic relationships—the cost-benefit analysis occurs when each party has goods that the other parties value. Social exchange theory suggests that these calculations occur in romantic relationships, friendships, professional relationships, and ephemeral relationships as simple as exchanging words with a customer at the cash register. Social exchange theory says that if the costs of the relationship are higher than the rewards, such as if a lot of effort or money were put into a relationship and not reciprocated, then the relationship may be terminated or abandoned.

In cultural anthropology, reciprocity refers to the non-market exchange of goods or labour ranging from direct barter to forms of gift exchange where a return is eventually expected as in the exchange of birthday gifts. It is thus distinct from the true gift, where no return is expected.

Kula, also known as the Kula exchange or Kula ring, is a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring was made famous by Bronisław Malinowski, considered the father of modern anthropology. He used this test case to argue for the universality of rational decision-making and for the cultural nature of the object of their effort. Malinowski's seminal work on the topic, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), directly confronted the question, "Why would men risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets?" Malinowski carefully traced the network of exchanges of bracelets and necklaces across the Trobriand Islands, and established that they were part of a system of exchange, and that this exchange system was clearly linked to political authority.

Reciprocity is a crucial aspect of how people interact and live in society but researchers who study these interactions have often overlooked its importance. Reciprocity, as a fundamental principle in social psychology, revolves around the concept that individuals tend to respond to the actions of others in a manner that mirrors the positive or negative nature of those actions. It involves a mutual exchange of behaviors and reactions, where individuals reciprocate the same type of behavior they have received from others. People's choices in how they behave are mostly based on what they can gain from others in return, while feelings of trust, liking, and togetherness are strongly influenced by the idea of giving and receiving equally

Koha is a New Zealand Māori custom which can be translated as gift, present, offering, donation or contribution.

The norm of reciprocity requires that people repay in kind what others have done for them. It can be understood as the expectation that people will respond to each other by returning benefits for benefits, and with either indifference or hostility to harms. The social norm of reciprocity may take different forms in different areas of social life, or in different societies. This is distinct from related ideas such as gratitude, the Golden Rule, or mutual goodwill. See reciprocity for an analysis of the concepts involved.

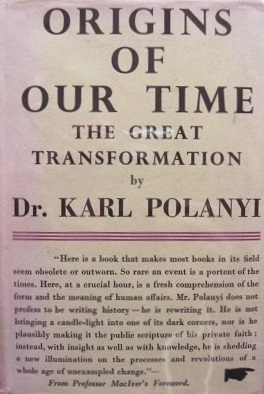

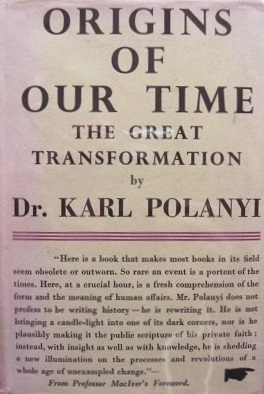

The Great Transformation is a book by Karl Polanyi, a Hungarian political economist. First published in 1944 by Farrar & Rinehart, it deals with the social and political upheavals that took place in England during the rise of the market economy. Polanyi contends that the modern market economy and the modern nation-state should be understood not as discrete elements but as a single human invention, which he calls the "Market Society".

Sister exchange is a type of marriage agreement where two sets of siblings marry each other. In order to get married, a man needs to persuade his sister to marry the bride's brother. It is practised as a primary method of organising marriages in 3% of the world's societies: in Australia, Melanesia, Amazonia and Sub-Saharan Africa; and can replace other methods in 1.4% of the societies.

Ongka's Big Moka: The Kawelka of Papua New Guinea is a 1970s documentary film, part of Granada Television's Disappearing World Series which ran from 1969–1993. It was first aired in the UK on 11 December 1974, and was subsequently aired in the US in 1976. Andrew Strathern served as consulting anthropologist for the film.

A big man is a highly influential individual in a tribe, especially in Melanesia and Polynesia. Such a person may not have formal tribal or other authority, but can maintain recognition through skilled persuasion and wisdom. The big man has a large group of followers, both from his clan and from other clans. He provides his followers with protection and economic assistance, in return receiving support which he uses to increase his status.

In cultural anthropology and sociology, redistribution refers to a system of economic exchange involving the centralized collection of goods from members of a group followed by the redivision of those goods among those members. It is a form of reciprocity. Redistribution differs from simple reciprocity, which is a dyadic back-and-forth exchange between two parties. Redistribution, in contrast, consists of pooling, a system of reciprocities. It is a within group relationship, whereas reciprocity is a between relationship. Pooling establishes a centre, whereas reciprocity inevitably establishes two distinct parties with their own interests. While the most basic form of pooling is that of food within the family, it is also the basis for sustained community efforts under a political leader.

"Gifting remittances" describes a range of scholarly approaches relating remittances to anthropological literature on gift giving. The terms draws on Lisa Cliggett's "gift remitting", but is used to describe a wider body of work. Broadly speaking, remittances are the money, goods, services, and knowledge that migrants send back to their home communities or families. Remittances are typically considered as the economic transactions from migrants to those at home. While remittances are also a subject of international development and policy debate and sociological and economic literature, this article focuses on ties with literature on gifting and reciprocity or gift economy founded largely in the work of Marcel Mauss and Marshall Sahlins. While this entry focuses on remittances of money or goods, remittances also take the form of ideas and knowledge. For more on these, see Peggy Levitt's work on "social remittances" which she defines as "the ideas, behaviors, identities, and social capital that flow from receiving to sending country communities."

The social norm of reciprocity is the expectation that people will respond to each other in similar ways—responding to gifts and kindnesses from others with similar benevolence of their own, and responding to harmful, hurtful acts from others with either indifference or some form of retaliation. Such norms can be crude and mechanical, such as a literal reading of the eye-for-an-eye rule lex talionis, or they can be complex and sophisticated, such as a subtle understanding of how anonymous donations to an international organization can be a form of reciprocity for the receipt of very personal benefits, such as the love of a parent.

Inalienable possessions are things such as land or objects that are symbolically identified with the groups that own them and so cannot be permanently severed from them. Landed estates in the Middle Ages, for example, had to remain intact and even if sold, they could be reclaimed by blood kin. As a legal classification, inalienable possessions date back to Roman times. According to Barbara Mills, "Inalienable possessions are objects made to be kept, have symbolic and economic power that cannot be transferred, and are often used to authenticate the ritual authority of corporate groups".

Several authors have used the terms organ gifting and "tissue gifting" to describe processes behind organ and tissue transfers that are not captured by more traditional terms such as donation and transplantation. The concept of "gift of life" in the U.S. refers to the fact that "transplantable organs must be given willingly, unselfishly, and anonymously, and any money that is exchanged is to be perceived as solely for operational costs, but never for the organs themselves". "Organ gifting" is proposed to contrast with organ commodification. The maintenance of a spirit of altruism in this context has been interpreted by some as a mechanism through which the economic relations behind organ/tissue production, distribution, and consumption can be disguised. Organ/tissue gifting differs from commodification in the sense that anonymity and social trust are emphasized to reduce the offer and request of monetary compensation. It is reasoned that the implementation of the gift-giving analogy to organ transactions shows greater respect for the diseased body, honors the donor, and transforms the transaction into a morally acceptable and desirable act that is borne out of voluntarism and altruism.

Christopher A. Gregory is an Australian economic anthropologist. He is based at Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, and has also taught at University of Manchester- where he was made Professor of Political and Economic Anthropology. He studied Economics at University of New South Wales and ANU before pursuing anthropology, following a period in Papua New Guinea. His main research has been in Papua New Guinea and Bastar District, central India, and he also co-authored a research methods manual for economic anthropology, 'Observing the Economy', with Jon Altman.