The Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography is one of the American Pulitzer Prizes annually awarded for journalism. From 2000 it has used the "breaking news" name but it is considered a continuation of the Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography, which was awarded from 1968 to 1999. Prior to 1968, a single Prize was awarded for photojournalism, the Pulitzer Prize for Photography, which was replaced in that year by Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography and Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography.

The Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography is one of the American Pulitzer Prizes annually awarded for journalism. It recognizes a distinguished example of feature photography in black and white or color, which may consist of a photograph or photographs, a sequence or an album.

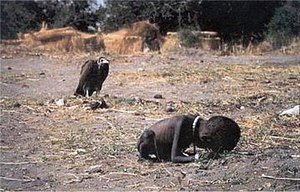

Kevin Carter was a South African photojournalist and member of the Bang-Bang Club. He was the recipient in 1994 of a Pulitzer Prize for his photograph depicting the 1993 famine in Sudan. He died by suicide at the age of 33. His story is depicted in the book The Bang-Bang Club, written by Greg Marinovich and João Silva and published in 2000.

Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) was a consortium of United Nations agencies and approximately 35 non-governmental organizations operating in southern Sudan to provide humanitarian assistance throughout war-torn and drought-afflicted regions in the South. Operation Lifeline Sudan was established in April 1989 in response to a devastating war-induced famine and other humanitarian consequences of the Second Sudanese Civil War between the Sudanese government and South Sudanese rebels. It was the result of negotiations between the UN, the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) to deliver humanitarian assistance to all civilians in need, regardless of their location or political affiliation. This included over 100,000 returnees from Itang in Ethiopia in 1991. Lokichogio was the primary forward operations hub for OLS.

Dr. Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon is a South Sudanese politician who serves as the First Vice President of South Sudan.

David Hume Kennerly is an American photographer. He won the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for his portfolio of photographs of the Vietnam War, Cambodia, East Pakistani refugees near Calcutta, and the Ali-Frazier fight in Madison Square Garden. He has photographed every American president since Lyndon B Johnson. He is the first presidential scholar at the University of Arizona.

The following are the Pulitzer Prizes for 1994.

The Bang-Bang Club was a group of four conflict photographers, Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and João Silva, active within the townships of South Africa between 1990 and 1994 during the transition from the apartheid system to democracy. This period included much factional violence, particularly fighting between African National Congress and Inkatha Freedom Party supporters, after the lifting of the bans on both political parties. The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging and other groups were also involved in the violence.

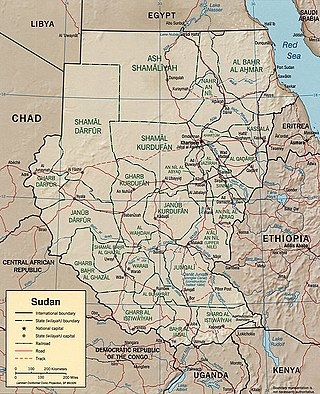

The famine in Sudan in 1998 was a humanitarian disaster caused mainly by human rights abuses, as well as drought and the failure of the international community to react to the famine risk with adequate speed. The worst affected area was Bahr el Ghazal in southwestern Sudan. In this region over 70,000 people died during the famine.

Horst Faas was a German photo-journalist and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner. He is best known for his images of the Vietnam War.

João Silva is a Portuguese-born South African war photographer. He is the last working member of the Bang-Bang Club, a group of photographers who covered South Africa from the time of Nelson Mandela's release from prison in 1990, to the country's first multiracial elections in 1994. He has worked in Africa, the Balkans, Central Asia, Russia, and the Middle East.

Greg Marinovich is a South African photojournalist, filmmaker, photo editor, and member of the Bang-Bang Club.

Ken Oosterbroek was a South African photojournalist and member of the Bang-Bang Club. He worked for The Star in Johannesburg, which was South Africa's biggest daily broadsheet. He won numerous photography awards for his work.

The Bang-Bang Club may refer to:

The Bang Bang Club is a 2010 Canadian-South African biographical drama film written and directed by Steven Silver and stars Ryan Phillippe as Greg Marinovich, Malin Åkerman as Robin Comley, Taylor Kitsch as Kevin Carter, Frank Rautenbach as Ken Oosterbroek and Neels Van Jaarsveld as João Silva. They portray the lives of four photojournalists active within the townships of South Africa during the apartheid period, particularly between 1990 and 1994, from when Nelson Mandela was released from prison to the 1994 elections.

The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War is a 2000 autobiographical styled text about the Bang-Bang Club, a group of four South African photographers active within the townships of South Africa during the apartheid period, particularly between 1990 and 1994. The journalists were Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and João Silva. The book was co-authored by two of the journalists, Marinovich and Silva.

Flower Power is the title of a photograph taken by American photographer Bernie Boston for the now-defunct newspaper The Washington Evening Star. Taken on October 21, 1967, during the March on the Pentagon by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the photo shows protester George Harris placing a carnation into the barrel of an M14 rifle held by a soldier of the 503rd Military Police Battalion (Airborne).

In the early months of 2017, parts of South Sudan experienced a famine following several years of instability in the country's food supply caused by war and drought. The famine, largely focused in the northern part of the country, affected an estimated five million people. In May 2017, the famine was officially declared to have weakened to a state of severe food insecurity.

The 1993 famine in Sudan occurred in 1993. It came amidst political unrest and civil war in Sudan.

Photography in Sudan refers to both historical as well as to contemporary photographs taken in the cultural history of today's Republic of the Sudan. This includes the former territory of present-day South Sudan, as well as what was once Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and some of the oldest photographs from the 1860s, taken during the Turkish-Egyptian rule (Turkiyya). As in other countries, the growing importance of photography for mass media like newspapers, as well as for amateur photographers has led to a wider photographic documentation and use of photographs in Sudan during the 20th century and beyond. In the 21st century, photography in Sudan has undergone important changes, mainly due to digital photography and distribution through social media and the Internet.