Related Research Articles

Snohomish County is a county located in the U.S. state of Washington. With a population of 827,957 as of the 2020 census, it is the third-most populous county in Washington, after nearby King and Pierce counties, and the 72nd-most populous in the United States. The county seat and largest city is Everett. The county forms part of the Seattle metropolitan area, which also includes King and Pierce counties to the south.

Arlington is a city in northern Snohomish County, Washington, United States, part of the Seattle metropolitan area. The city lies on the Stillaguamish River in the western foothills of the Cascade Range, adjacent to the city of Marysville. It is approximately 10 miles (16 km) north of Everett, the county seat, and 40 miles (64 km) north of Seattle, the state's largest city. As of the 2020 U.S. census, Arlington had a population of 19,868; its estimated population is 20,075 as of 2021.

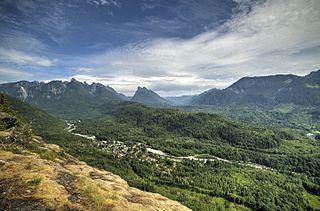

Darrington is a town in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located in a North Cascades mountain valley formed by the Sauk and North Fork Stillaguamish rivers. Darrington is connected to nearby areas by State Route 530, which runs along the two rivers towards the city of Arlington, located 30 miles (48 km) to the west, and Rockport. It had a population of 1,347 at the 2010 census.

Edmonds is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located in the southwest corner of the county, facing Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains to the west. The city is part of the Seattle metropolitan area and is located 15 miles (24 km) north of Seattle and 18 miles (29 km) southwest of Everett. With a population of 42,853 residents in the 2020 U.S. census, Edmonds is the third most populous city in the county.

Index is a town in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. The population was 155 at the 2020 census.

Lynnwood is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. The city is part of the Seattle metropolitan area and is located 16 miles (26 km) north of Seattle and 13 miles (21 km) south of Everett, near the junction of Interstate 5 and Interstate 405. It is the fourth-largest city in Snohomish County, with a population of 38,568 in the 2020 U.S. census.

Marysville is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States, part of the Seattle metropolitan area. The city is located 35 miles (56 km) north of Seattle, adjacent to Everett on the north side of the Snohomish River delta. It is the second-largest city in Snohomish County after Everett, with a population of 70,714 at the time of the 2020 U.S. census. As of 2015, Marysville was also the fastest-growing city in Washington state, growing at an annual rate of 2.5 percent.

Monroe is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located at the confluence of the Skykomish, Snohomish, and Snoqualmie rivers near the Cascade foothills, about 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Seattle. Monroe's population was 19,699 as of the 2020 census.

Mountlake Terrace is a suburban city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It lies on the southern border of the county, adjacent to Shoreline and Lynnwood, and is 13 miles (21 km) north of Seattle. The city had a population of 19,909 people counted in the 2010 census.

Mukilteo is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located on Puget Sound between Edmonds and Everett, approximately 25 miles (40 km) north of Seattle. The city had a population of 20,254 at the 2010 census and an estimated 2019 population of 21,441.

Snohomish is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. The population was 10,126 at the 2020 census. It is located on the Snohomish River, southeast of Everett and northwest of Monroe. Snohomish lies at the intersection of U.S. Route 2 and State Route 9. The city's airport, Harvey Airfield, is located south of downtown and used primarily for general aviation.

Stanwood is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. The city is located 50 miles (80 km) north of Seattle, at the mouth of the Stillaguamish River near Camano Island. As of the 2020 census, its population is 7,705.

Bothell is a city in King and Snohomish counties in the U.S. state of Washington. It is part of the Seattle metropolitan area, situated near the northeast end of Lake Washington in the Eastside region. Bothell had a population of 48,161 residents as of the 2020 census.

Community Transit (CT) is the public transit authority of Snohomish County, Washington, United States, excluding the city of Everett, in the Seattle metropolitan area. It operates local bus, paratransit and vanpool service within Snohomish County, as well as commuter buses to Downtown Seattle and Northgate station. CT is publicly funded, financed through sales taxes, and farebox revenue, with an operating budget of $133.2 million. In 2023, the system had a ridership of 7,133,700, or about 24,700 per weekday as of the first quarter of 2024, placing it fourth among transit agencies in the Puget Sound region. The city of Everett, which serves as the county seat, is served by Everett Transit, a municipal transit system.

The Everett Herald is a daily newspaper based in Everett, Washington, United States. It is owned by Sound Publishing, Inc. The paper serves residents of Snohomish County in the Seattle metropolitan area.

State Route 530 (SR 530) is a state highway in western Washington, United States. It serves Snohomish and Skagit counties, traveling 50.52 miles (81.30 km) from an interchange with Interstate 5 (I-5) southwest of Arlington past SR 9 in Arlington and Darrington to end at SR 20 in Rockport. Serving the communities of Arlington, Arlington Heights, Oso, Darrington and Rockport, the roadway travels parallel to a fork of the Stillaguamish River from Arlington to Darrington, the Sauk River from Darrington to Rockport and the Whitehorse Trail from Arlington to Darrington.

The Washington Interscholastic Activities Association (WIAA) is the governing body of athletics and activities for secondary education schools in the state of Washington. As of February 2011, the private, 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization consists of nearly 800 member high schools and middle/junior high schools, both public and private.

State Route 204 (SR 204) is a short state highway in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It connects U.S. Route 2 (US 2) at the eastern end of the Hewitt Avenue Trestle to the city of Lake Stevens, terminating at a junction with SR 9. The highway runs for a total length of 2.4 miles (3.9 km) and passes through several suburban neighborhoods.

State Route 528 (SR 528) is an east–west state highway in Snohomish County, Washington, located entirely within the city of Marysville. It travels 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from an interchange with Interstate 5 (I-5) in downtown Marysville to a junction with SR 9. The four-lane highway uses two local streets—4th Street and 64th Street—and primarily functions as a commuter route to the eastern outskirts of Marysville.

Everett is the county seat and most populous city of Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is 25 miles (40 km) north of Seattle and is one of the main cities in the metropolitan area and the Puget Sound region. Everett is the seventh-most populous city in the state by population, with 110,629 residents as of the 2020 census. The city is primarily situated on a peninsula at the mouth of the Snohomish River along Port Gardner Bay, an inlet of Possession Sound, and extends to the south and west.

References

- Investigative series by Gary Larson

- Larson, Gary (July 13, 1979). "Mystery surrounds quiet county farm". Everett Herald. p. 1A.

- Larson, Gary (July 14, 1979). "Secretive religious group in county? Ex-members tell stories of hard work, restricted freedom at Eden Farms". Everett Herald. p. 1A.

- Larson, Gary (July 16, 1979). "Religion or business? Leader's views differ from those of some followers — and donors". Everett Herald. p. 1A.

- Larson, Gary (July 17, 1979). "Leader of 'the group' pushed a loyalty rite". Everett Herald. p. 3A.

- Larson, Gary (July 18, 1979). "Youths tell story of Spartan life on the farm". Everett Herald. p. 3A.

- Larson, Gary (July 19, 1979). "Rinaldo took active role in political races". Everett Herald.

- Other articles

- Haley, Jim (July 14, 1979). "Psychiatric exam sought for Rinaldo". Everett Herald.

- Haley, Jim (July 24, 1979). "Two Rinaldo associates enter innocent pleas". Everett Herald. p. 8A.

- Haley, Jim (November 16, 1979). "Group was ruled by fear, jury told". Everett Herald. p. 1A.

- Haley, Jim (November 17, 1979). "Testimony focuses on alleged sex contacts". Everett Herald. p. 7B.

- Haley, Jim (November 27, 1979). "Witnesses challenged in morals trial". Everett Herald. p. 9B.

- Haley, Jim (November 28, 1979). "Conflicting testimony abounds in Eden Farms trial". Everett Herald. p. 9A.

- Haley, Jim (November 30, 1979). "Rinaldo trial focuses on witnesses' reputations". Everett Herald. p. 3A.

- Haley, Jim (December 1, 1979). "Rinaldo trial down to its final stages". Everett Herald. p. 6A.

- Haley, Jim (December 13, 1979). "Prosecutor to ask judge to order psychiatric test". Everett Herald. p. 9A.

- "Sex-label proof eyed". Spokane Chronicle. Associated Press. December 22, 1982. p. 5.

- "State Supreme Court takes limits off juvenile sentencing". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. December 23, 1982. p. 16.