This article may be a rough translation from German. It may have been generated, in whole or in part, by a computer or by a translator without dual proficiency.(November 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

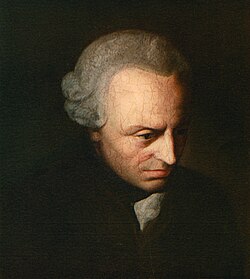

| Immanuel Kant |

|---|

|

| Category • |

In Kantian philosophy, the thing-in-itself (German : Ding an sich) is the status of objects as they are, independent of representation and observation. The concept of the thing-in-itself was introduced by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, and over the following centuries was met with controversy among later philosophers. [1] It is closely related to Kant's concept of noumena or the objects of inquiry, as opposed to phenomena, its manifestations.