Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity; and from collective property, which is owned by a group of non-governmental entities. Private property can be either personal property or capital goods. Private property is a legal concept defined and enforced by a country's political system.

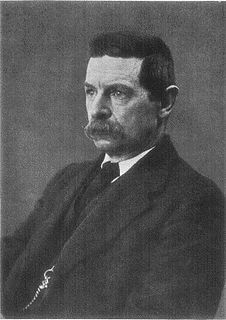

Sidney James Webb, 1st Baron Passfield, was a British socialist, economist, reformer and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. He was one of the early members of the Fabian Society in 1884, along with George Bernard Shaw. Along with his wife Beatrice Webb, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, Edward R. Pease, Hubert Bland, and Sydney Olivier, Shaw and Webb turned the Fabian Society into the pre-eminent political-intellectual society of England during the Edwardian era and beyond. He wrote the original Clause IV for the British Labour Party.

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield,, was an English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer. It was Webb who coined the term "collective bargaining". She was among the founders of the London School of Economics and played a crucial role in forming the Fabian Society.

Christian socialism is a form of religious socialism based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. Many Christian socialists believe capitalism to be idolatrous and rooted in greed, which some Christian denominations consider a mortal sin. Christian socialists identify the cause of inequality to be the greed that they associate with capitalism.

Hubert Bland was the husband of Edith Nesbit and was known for being an infamous libertine, a journalist, an early English socialist, and one of the founders of the Fabian Society.

George Douglas Howard Cole was an English political theorist, economist, writer and historian. As a libertarian socialist he was a long-time member of the Fabian Society and an advocate for the co-operative movement.

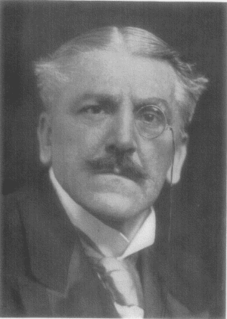

Sydney Haldane Olivier, 1st Baron Olivier, was a British civil servant. A Fabian and a member of the Labour Party, he served as Governor of Jamaica and as Secretary of State for India in the first government of Ramsay MacDonald. He was the uncle of the actor Laurence Olivier.

Stewart Duckworth Headlam (1847–1924) was an English Anglican priest who was involved in frequent controversy in the final decades of the nineteenth century. Headlam was a pioneer and publicist of Christian socialism, on which he wrote a pamphlet for the Fabian Society, and a supporter of Georgism. He is noted for his role as the founder and warden of the Guild of St Matthew and for helping to bail Oscar Wilde from prison at the time of his trials.

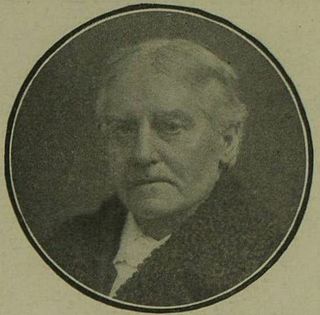

Edward Reynolds Pease was an English writer and a founding member of the Fabian Society.

The New Age was a British literary magazine, noted for its wide influence under the editorship of A. R. Orage from 1907 to 1922. It began life in 1894 as a publication of the Christian socialist movement; but in 1907 as a radical weekly edited by Joseph Clayton, it was struggling. In May of that year, Alfred Orage and Holbrook Jackson, who had been running the Leeds Arts Club, took over the journal with financial help from George Bernard Shaw. Jackson acted as co-editor only for the first year, after which Orage edited it alone until he sold it in 1922. By that time his interests had moved towards mysticism, and the quality and circulation of the journal had declined. According to a Brown University press release, "The New Age helped to shape modernism in literature and the arts from 1907 to 1922". It ceased publication in 1938. Orage was also associated with The New English Weekly (1932–1949) as editor during its first two years of operation.

A Modern Utopia is a 1905 novel by H. G. Wells.

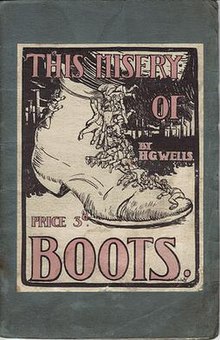

New Worlds for Old (1908), which appeared in some later editions with the subtitle "A Plain Account of Modern Socialism," was one of several books and pamphlets that H.G. Wells wrote about the socialist future in the period 1901-1908, while he was engaged in an effort to reform the Fabian Society.

Free association is a relationship among individuals where there is no state, social class, authority, or private ownership of means of production. Once private property is abolished, individuals are no longer deprived of access to means of production enabling them to freely associate to produce and reproduce their own conditions of existence and fulfill their individual and creative needs and desires. The term is used by anarchists and Marxists and is often considered a defining feature of a fully developed communist society.

The Future in America: A Search After Realities is a 1906 travel essay by H. G. Wells recounting his impressions from the first of half a dozen visits he would make to the United States. The book consists of fifteen chapters and a concluding "envoy".

First and Last Things is a 1908 work of philosophy by H. G. Wells setting forth his beliefs in four "books" entitled "Metaphysics," "Of Belief," "Of General Conduct," and "Some Personal Things." Parts of the book were published in the Independent Magazine in July and August 1908. Wells revised the book extensively in 1917, in response to his religious conversion, but later published a further revision in 1929 that restored much of the book to its earlier form. Its main intellectual influences are Darwinism and certain German thinkers Wells had read, such as August Weismann. The pragmatism of William James, who had become a friend of Wells, was also an influence.

Liberal socialism is a socialist political philosophy that incorporates liberal principles. Liberal socialism does not have the goal of completely abolishing capitalism and replacing it with socialism, but it instead supports a mixed economy that includes both private property and social ownership in capital goods. Although liberal socialism unequivocally favors a market-based economy, it identifies legalistic and artificial monopolies to be the fault of capitalism and opposes an entirely unregulated economy. It considers both liberty and equality to be compatible and mutually dependent on each other.

Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought, generally known as Anticipations, was written by H.G. Wells at the age of 34. He later called the book, which became a bestseller, "the keystone to the main arch of my work." His most recent biographer, however, calls the volume "both the starting point and the lowest point in Wells's career as a social thinker."

Ethical socialism is a political philosophy that appeals to socialism on ethical and moral grounds as opposed to economic, egoistic and consumeristic grounds. It emphasizes the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principles of service, cooperation and social justice while opposing possessive individualism. In contrast to socialism inspired by rationalism, historical materialism, neoclassical economics and Marxist theory which base their appeals for socialism on grounds of economic efficiency, rationality, or historical inevitability, ethical socialism focuses on the moral and ethical reasons for advocating socialism.