Tono-Bungay is a realist semiautobiographical novel written by H. G. Wells and first published in book form in 1909. It has been called "arguably his most artistic book". It had been serialised before book publication, both in the United States, in The Popular Magazine, beginning in the issue of September 1908, and in Britain, in The English Review, beginning in the magazine's first issue in December 1908.

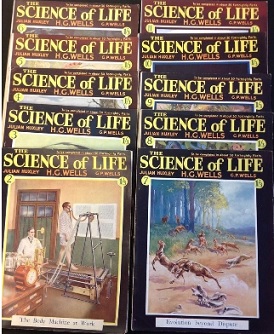

The Science of Life is a book written by H. G. Wells, Julian Huxley and G. P. Wells, published in three volumes by The Waverley Publishing Company Ltd in 1929–30, giving a popular account of all major aspects of biology as known in the 1920s. It has been called "the first modern textbook of biology" and "the best popular introduction to the biological sciences". Wells's most recent biographer notes that The Science of Life "is not quite as dated as one might suppose".

A Modern Utopia is a 1905 novel by H. G. Wells.

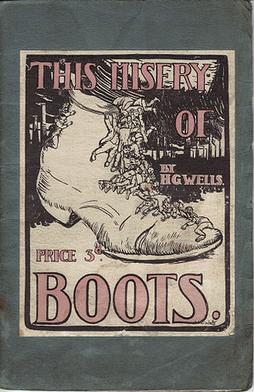

This Misery of Boots is a 1907 political tract by H. G. Wells advocating socialism. Published by the Fabian Society, This Misery of Boots is the expansion of a 1905 essay with the same name. Its five chapters condemn private property in land and means of production and calls for their expropriation by the state "not for profit, but for service."

The Wonderful Visit is an 1895 novel by H. G. Wells. With an angel—a creature of fantasy unlike a religious angel—as protagonist and taking place in contemporary England, the book could be classified as contemporary fantasy, although the genre was not recognised in Wells's time. The Wonderful Visit also has strong satirical themes, gently mocking customs and institutions of Victorian England as well as idealistic rebellion itself.

Mr. Britling Sees It Through is H. G. Wells's "masterpiece of the wartime experience in south eastern England." The novel was published in September 1916.

The Soul of a Bishop is a 1917 novel by H. G. Wells.

The World of William Clissold is a 1926 novel by H. G. Wells published initially in three volumes. The first volume was published in September to coincide with Wells's sixtieth birthday, and the second and third volumes followed at monthly intervals.

Meanwhile is a 1927 novel by H. G. Wells set in an Italian villa early in 1926.

The Story of a Great Schoolmaster is a 1924 biography of Frederick William Sanderson (1857–1922) by H. G. Wells. It is the only biography Wells wrote. Sanderson was a personal friend, having met Wells in 1914 when his sons George Philip ('Gip'), born in 1901, and Frank Richard, born in 1903, became pupils at Oundle School, of which Sanderson was headmaster from 1892 to 1922. After Sanderson died, while giving a lecture at University College London, at which he was introduced by Wells, the famous author agreed to help produce a biography to raise money for the school. But in December 1922, after disagreements emerged with Sanderson's widow about his approach to the subject, Wells withdrew from the official biography and published his own work separately.

The New Machiavelli is a 1911 novel by H. G. Wells that was serialised in the English Review in 1910. Because its plot notoriously derived from Wells's affair with Amber Reeves and satirised Beatrice and Sidney Webb, it was "the literary scandal of its day."

The Future in America: A Search After Realities is a 1906 travel essay by H. G. Wells recounting his impressions from the first of half a dozen visits he would make to the United States. The book consists of fifteen chapters and a concluding "envoy".

The Passionate Friends is a 1913 coming of age novel by H. G. Wells detailing the life and travels of a young man. It is notable as the first introduction of Wells's notion of an "open conspiracy" of individuals to achieve a world state.

The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman is a 1914 novel by H. G. Wells.

Bealby: A Holiday is a 1915 comic novel by H. G. Wells.

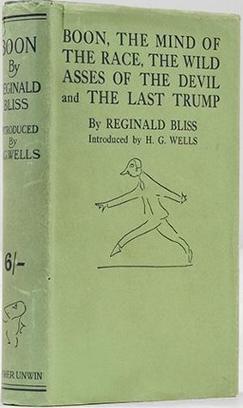

Boon is a 1915 work of literary satire by H. G. Wells. It purports, however, to be by the fictional character Reginald Bliss, and for some time after publication Wells denied authorship. Boon is best known for its part in Wells's debate on the nature of literature with Henry James, who is caricatured in the book. But in Boon Wells also mocks himself, calling into question and ridiculing a notion he held dear—that of humanity's collective consciousness.

The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind by H. G. Wells is the final work of a trilogy of which the first volumes were The Outline of History (1919–1920) and The Science of Life (1929). Wells conceived of the three parts of his trilogy as, respectively, "a survey of history, of the science of life, and of existing conditions." Intended as an unprecedented "picture of all mankind to-day" in all its manifold activities, he called it "the least finished work . . . because it is the most novel." He hoped the volumes would play a role in the open conspiracy to establish a progressive world government that he had been promoting since the mid-1920s.

The Bulpington of Blup is a 1932 novel by H. G. Wells. It is a character study analyzing the psychological sources of resistance to Wellsian ideology, and was influenced by Wells's acquaintance with Carl Gustav Jung and his ideas.

Certain Personal Matters is an 1897 collection of essays selected by H. G. Wells from among the many short essays and ephemeral pieces he had written since 1893. The book consists of thirty-nine pieces ranging from about eight hundred to two thousand words in length. A one-shilling reprint was issued in 1901 by T. Fisher Unwin.

Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought, generally known as Anticipations, was written by H.G. Wells at the age of 34. He later called the book, which became a bestseller, "the keystone to the main arch of my work." His most recent biographer, however, calls the volume "both the starting point and the lowest point in Wells's career as a social thinker."