The League of Nations was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. The main organisation ceased operations on 18 April 1946 when many of its components were relocated into the new United Nations. As the template for modern global governance, the League profoundly shaped the modern world.

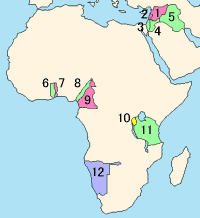

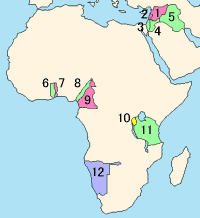

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing the internationally agreed terms for administering the territory on behalf of the League of Nations. Combining elements of both a treaty and a constitution, these mandates contained minority rights clauses that provided for the rights of petition and adjudication by the Permanent Court of International Justice.

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which led to the war. The other Central Powers on the German side signed separate treaties. Although the armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, and agreed certain principles and conditions including the payment of reparations, it took six months of Allied negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. Germany was not allowed to participate in the negotiations before signing the treaty.

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all of Earth and humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. He was secretary of the Zoological Society of London (1935–1942), the first director of UNESCO, a founding member of the World Wildlife Fund, the president of the British Eugenics Society (1959–1962), and the first president of the British Humanist Association.

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress by President Woodrow Wilson. However, his main Allied colleagues were skeptical of the applicability of Wilsonian idealism.

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, new ones were formed, boundaries were redrawn, international organizations were established, and many new and old ideologies took a firm hold in people's minds. Additionally, culture in the nations involved was greatly changed. World War I also had the effect of bringing political transformation to most of the principal parties involved in the conflict, transforming them into electoral democracies by bringing near-universal suffrage for the first time in history, as in Germany, Great Britain, and the United States.

The Paris Peace Conference was a set of formal and informal diplomatic meetings in 1919 and 1920 after the end of World War I, in which the victorious Allies set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers. Dominated by the leaders of Britain, France, the United States and Italy, the conference resulted in five treaties that rearranged the maps of Europe and parts of Asia, Africa and the Pacific Islands, and also imposed financial penalties. Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and the other losing nations were not given a voice in the deliberations; this later gave rise to political resentments that lasted for decades. The arrangements made by this conference are considered one of the great watersheds of 20th-century geopolitical history.

Constance Clara Garnett was an English translator of nineteenth-century Russian literature. She was the first English translator to render numerous volumes of Anton Chekhov's work into English and the first to translate almost all of Fyodor Dostoevsky's fiction into English. She also rendered works by Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Goncharov, Alexander Ostrovsky, and Alexander Herzen into English. Altogether, she translated 71 volumes of Russian literature, many of which are still in print today.

Article 231, often known as the "War Guilt" clause, was the opening article of the reparations section of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War between the German Empire and the Allied and Associated Powers. The article did not use the word guilt but it served as a legal basis under which Germany was to pay reparations for damages caused during the war.

The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) is a book written and published by the British economist John Maynard Keynes. After the First World War, Keynes attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as a delegate of the British Treasury. At the conference as a representative of the British Treasury and deputy to the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the Supreme Economic Council, but became ill and on his return found that there was 'no hope' of an economically sustainable settlement, and so resigned. In this book, he presents his arguments for a much less onerous treaty for a wider readership, not just for the sake of German civilians but for the sake of the economic well-being of all of Europe and beyond, including the Allied Powers, which in his view the Treaty of Versailles and its associated treaties endangered.

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of United States President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and promoting world peace. He was a leading advocate of the League of Nations to enable the international community to avoid wars and end hostile aggression. Wilsonianism is a form of liberal internationalism.

Reginald Clifford Allen, 1st Baron Allen of Hurtwood, known as Clifford Allen, was a British politician, leading member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), and prominent pacifist.

Woodrow Wilson's tenure as the 28th president of the United States lasted from March 4, 1913, until March 4, 1921. He was largely incapacitated the last year and a half. He became president after winning the 1912 election. Wilson was a Democrat who previously served as governor of New Jersey. He gained a large majority in the electoral vote and a 42% plurality of the popular vote in a four-candidate field. Wilson was re-elected in 1916 by a narrow margin. Despite his New Jersey base, most Southern leaders worked with him as a fellow Southerner. He was succeeded by Republican Warren Harding, who won the 1920 election.

The League to Enforce Peace was a non-state American organization established in 1915 to promote the formation of an international body for world peace. It was formed at Independence Hall in Philadelphia by American citizens concerned by the outbreak of World War I in Europe. Support for the league dissolved and it ceased operations by 1923.

During the First World War there were a number of conferences of the socialist parties of the Entente or Allied powers.

H. G. Wells (1866–1946) was a prolific English writer in many genres, including the novel, history, politics, and social commentary, and textbooks and rules for war games. Wells called his political views socialist.

The diplomatic history of World War I covers the non-military interactions among the major players during World War I. For the domestic histories of participants see home front during World War I. For a longer-term perspective see international relations (1814–1919) and causes of World War I. For the following (post-war) era see international relations (1919–1939). The major "Allies" grouping included Great Britain and its empire, France, Russia, Italy and the United States. Opposing the Allies, the major Central Powers included Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) and Bulgaria. Other countries also joined the Allies. For a detailed chronology see timeline of World War I.

The foreign policy under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson deals with American diplomacy, and political, economic, military, and cultural relationships with the rest of the world from 1913 to 1921. Although Wilson had no experience in foreign policy, he made all the major decisions, usually with the top advisor Edward M. House. His foreign policy was based on his messianic philosophical belief that America had the utmost obligation to spread its principles while reflecting the 'truisms' of American thought.

The United Kingdom and the League of Nations played central roles in the diplomatic history of the interwar period 1920-1939 and the search for peace. British activists and political leaders helped plan and found the League of Nations, provided much of the staff leadership, and Britain played a central role in most of the critical issues facing the League. The League of Nations Union was an important private organization that promoted the League in Britain. By 1924 the League was broadly popular and was featured in election campaigns. The Liberals were most supportive; the Conservatives least so. From 1931 onward, major aggressions by Japan, Italy, Spain and Germany effectively ruined the League in British eyes.