A plantation is the large-scale estate meant for farming that specializes in cash crops. The crops that are grown include cotton, coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar cane, sisal, oil seeds, oil palms, rubber trees, and fruits. Protectionist policies and natural comparative advantage have sometimes contributed to determining where plantations were located.

Slavery in the colonial area which later became the United States (1600–1776) developed from complex factors, and researchers have proposed several theories to explain the development of the institution of slavery and of the slave trade. Slavery strongly correlated with Europe's American colonies' need for labor, especially for the labor-intensive plantation economies of the sugar colonies in the Caribbean, operated by Great Britain, France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic.

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops grown on large farms called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash crops as a source of income. Prominent crops included cotton, rubber, sugar cane, tobacco, figs, rice, kapok, sisal, and species in the genus Indigofera, used to produce indigo dye.

Plantation was an early method of colonisation where settlers went in order to establish a permanent or semi-permanent colonial base, for example for planting tobacco or cotton. Such plantations were also frequently intended to promote Western culture and Christianity among nearby indigenous peoples, as can be seen in the early East-Coast plantations in America. Although the term "planter" to refer to a settler first appears as early as the 16th-century, the earliest true colonial plantation is usually agreed to be that of the Plantations of Ireland.

The Antebellum era was a period in the history of the Southern United States, from the late 18th century until the start of the American Civil War in 1861, marked by the economic growth of the South.

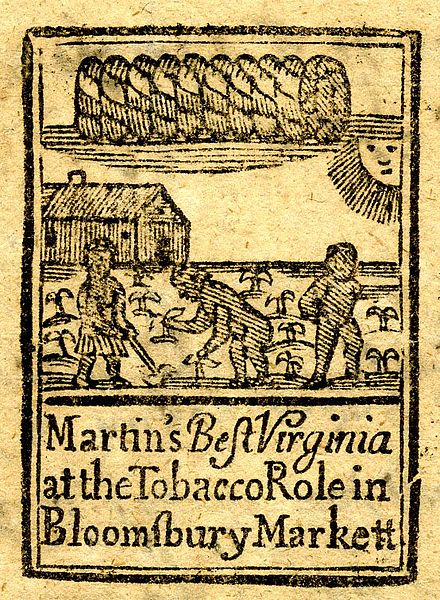

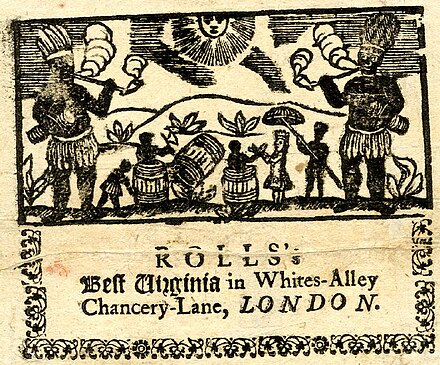

The tobacco colonies were those that lined the sea-level coastal region of English North America known as Tidewater, extending from a small part of Delaware south through Maryland and Virginia into the Albemarle Sound region of North Carolina. During the seventeenth century, the European demand for tobacco increased more than tenfold. This increased demand called for a greater supply of tobacco, and as a result, tobacco became the staple crop of the Chesapeake Bay Region.

The domestic slave trade, also known as the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the term for the domestic trade of slaves within the United States that reallocated slaves across states during the antebellum period. It was most significant in the early to mid-19th century, when historians estimate one million slaves were taken in a forced migration from the Upper South: Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia, to the territories and newly admitted states of the Deep South and the West Territories: Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

Partus sequitur ventrem, the literal translation being "delivery follows the stomach" often abbreviated to partus, was a legal doctrine concerning the slave or free status of children born in the English royal colonies. Incorporated into legislation in the British American colonies and later in the United States, partus held that the social status of a child followed that of his or her mother. Thus, any child born to an enslaved woman was born into slavery, regardless of the ancestry or citizenship of the father. This principle was widely adopted into the laws regarding slavery in the colonies and the following United States, eliminating financial responsibility of fathers for children born into slavery.

Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800, is a book written by historian Allan Kulikoff. Published in 1986, it is the first major study that synthesized the historiography of the colonial Chesapeake region of the United States. Tobacco and Slaves is a neo-Marxist study that explains the creation of a racial caste system in the tobacco-growing regions of Maryland and Virginia and the origins of southern slave society. Kulikoff uses statistics compiled from colonial court and church records, tobacco sales, and land surveys to conclude that economic, political, and social developments in the 18th-century Chesapeake established the foundations of economics, politics, and society in the 19th-century South.

Bermuda Hundred was the first administrative division in the English colony of Virginia. It was founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1613, six years after Jamestown. At the southwestern edge of the confluence of the Appomattox and James Rivers opposite City Point, annexed to Hopewell, Virginia in 1923, Bermuda Hundred was a port town for many years. The terminology "Bermuda Hundred" also included a large area adjacent to the town. In the colonial era, "hundreds" were large developments of many acres, arising from the English term to define an area which would support 100 homesteads. The port at the town of Bermuda Hundred was intended to serve other "hundreds" in addition to Bermuda Hundred.

The history of commercial tobacco production in the United States dates back to the 17th century when the first commercial crop was planted. The industry originated in the production of tobacco for pipes and snuff. Different war efforts in the world created a shift in demand and production of tobacco in the world and the American colonies. With the onset of the American Revolution trade with the colonies was interrupted which shifted trade to other countries in the world. During this shift there was an increase in demand for tobacco in the United States, where the demand for tobacco in the form of cigars and chewing tobacco increased. Other wars, such as the War of 1812 would introduce the Andalusian cigarette to the rest of Europe. This, accompanied with the American Civil War changed the production of tobacco in America to the manufactured cigarette.

Tobacco has a long history from its usages in the early Americas. It increased in popularity with the arrival of Spain to America, which introduced tobacco to the Europeans by whom it was heavily traded. Following the industrial revolution, cigarettes were becoming popularized in the New World as well as Europe, which fostered yet another unparalleled increase in growth. This remained so until scientific studies in mid 20th century demonstrated the negative health effects of tobacco smoking including lung and throat cancer.

During the British colonization of North America, the Thirteen Colonies provided England with much needed money and resources. However, the culture of the Southern and Chesapeake Colonies was different from that of the Northern and Middle Colonies and from that of their common British colonial power.

Slaves being bred in the United States includes any practice of slave ownership that aimed to systematically influence the reproduction of slaves in order to increase the wealth of slaveholders. Slave breeding included coerced sexual relations between male and female slaves, promoting pregnancies of slaves, and favoring female slaves who could produce a relatively large number of children. The purpose of slave breeding was to acquire new slaves without incurring the cost of purchase, and to fill labor shortages caused by the termination of the Atlantic slave trade.

Tobacco has a long history in the United States.

Plantations are an important aspect of the history of the American South, particularly the antebellum era. The mild subtropical climate, plentiful rainfall, and fertile soils of the southeastern United States allowed the flourishing of large plantations, where large numbers of workers, usually Africans held captive for slave labor, were required for agricultural production.

Plantation complexes in the Southern United States refers to the built environment that was common on agricultural plantations in the American South from the 17th into the 20th century. The complex included everything from the main residence down to the pens for livestock. A plantation originally denoted a settlement in which settlers were "planted" to establish a colonial base. Southern plantations were generally self-sufficient settlements that relied on the forced labor of slaves, similar to the way that a medieval manorial estate relied upon the forced labor of serfs.

The American gentry were members of the American upper classes, particularly early in the settlement of the United States.

The planter class, known alternatively in the United States as the Southern aristocracy, was a socio-economic caste of Pan-American society that dominated seventeenth- and eighteenth-century agricultural markets through the forced labor of enslaved Africans. The Atlantic slave trade permitted planters access to inexpensive labor for the planting and harvesting of crops such as tobacco, cotton, indigo, coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar cane, sisal, oil seeds, oil palms,hemp, rubber trees, and fruits.