Related Research Articles

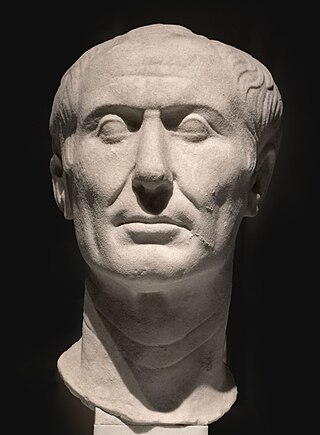

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

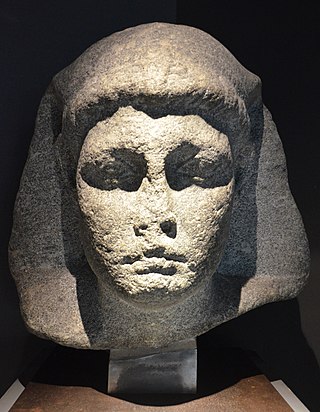

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler. A member of the Ptolemaic dynasty, she was a descendant of its founder Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great. Her first language was Koine Greek, and she is the only Ptolemaic ruler known to have learned the Egyptian language. After her death, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire, marking the end of the last Hellenistic-period state in the Mediterranean, a period which had lasted since the reign of Alexander.

Ptolemy XV Caesar, nicknamed Caesarion, was the last pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt, reigning with his mother Cleopatra VII from 2 September 44 BC until her death by 12 August 30 BC, then as sole ruler until his death was ordered by Octavian.

Publius Cornelius Dolabella was a Roman politician and general under the dictator Julius Caesar. He was by far the most important of the patrician Cornelii Dolabellae but he arranged for himself to be adopted into the plebeian Cornelii Lentuli so that he could become a plebeian tribune. He married Cicero's daughter, Tullia, although he frequently engaged in extramarital affairs. Throughout his life he was an extreme profligate, something that Plutarch wrote reflected ill upon his patron Julius Caesar.

The Roman emperor was the ruler and monarchical head of state of the Roman Empire, starting with the granting of the title Augustus to Octavian in 27 BC. The term "emperor" is a modern convention, and did not exist as such during the Empire. Often when a given Roman is described as becoming emperor in English, it reflects his taking of the title Augustus and later Basileus. Another title used was Imperator, originally a military honorific, and Caesar, originally a cognomen. Early emperors also used the title Princeps alongside other Republican titles, notably consul and Pontifex maximus.

The pater familias, also written as paterfamilias, was the head of a Roman family. The pater familias was the oldest living male in a household, and could legally exercise autocratic authority over his extended family. The term is Latin for "father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate". The form is archaic in Latin, preserving the old genitive ending in -ās, whereas in classical Latin the normal first declension genitive singular ending was -ae. The pater familias always had to be a Roman citizen.

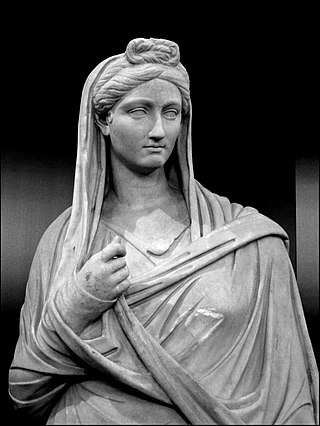

Freeborn women in ancient Rome were citizens (cives), but could not vote or hold political office. Because of their limited public role, women are named less frequently than men by Roman historians. But while Roman women held no direct political power, those from wealthy or powerful families could and did exert influence through private negotiations. Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia and Agrippina the Younger, who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena, a driving force in promoting Christianity.

Adoption in ancient Rome was primarily a legal procedure for transferring paternal power (potestas) to ensure succession in the male line within Roman patriarchal society. The Latin word adoptio refers broadly to "adoption", which was of two kinds: the transferral of potestas over a free person from one head of household to another; and adrogatio, when the adoptee had been acting sui iuris as a legal adult but assumed the status of unemancipated son for purposes of inheritance. Adoptio was a longstanding part of Roman family law pertaining to paternal responsibilities such as perpetuating the value of the family estate and ancestral rites (sacra), which were concerns of the Roman property-owning classes and cultural elite. During the Principate, adoption became a way to ensure imperial succession.

Arsinoë IV was the fourth of six children and the youngest daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes. Queen and co-ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt with her brother Ptolemy XIII from 48 BC – 47 BC, she was one of the last members of the Ptolemaic dynasty of ancient Egypt. Arsinoë IV was also the half sister of Cleopatra VII. For her role in conducting the siege of Alexandria against her sister Cleopatra, Arsinoë was taken as a prisoner of war to Rome by the Roman triumvir Julius Caesar following the defeat of Ptolemy XIII in the Battle of the Nile. Arsinoë was then exiled to the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in Roman Anatolia, but she was executed there by orders of triumvir Mark Antony in 41 BC at the behest of his lover Cleopatra VII.

Marcus Antonius Antyllus was a son of the Roman Triumvir Marc Antony. He was also called Antyllus, a nickname given to him by his father meaning "the Archer". Despite his three children by Cleopatra, Marc Antony designated Antyllus as his official heir, a requirement under Roman law and a designation that probably contributed to his execution at age 17 by Octavian.

Octavia the Younger was the elder sister of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, the half-sister of Octavia the Elder, and the fourth wife of Mark Antony. She was also the great-grandmother of the Emperor Caligula and Empress Agrippina the Younger, maternal grandmother of the Emperor Claudius, and paternal great-grandmother and maternal great-great-grandmother of the Emperor Nero.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom or Ptolemaic Empire was an Ancient Greek polity based in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Macedonian general Ptolemy I Soter, a companion of Alexander the Great, and ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC. Reigning for nearly three centuries, the Ptolemies were the longest and final dynasty of ancient Egypt, heralding a distinctly new era for religious and cultural syncretism between Greek and Egyptian culture.

Birth certificates for Roman citizens were introduced during the reign of Augustus. Until the time of Alexander Severus, it was required that these documents be written in Latin as a marker of "Romanness" (Romanitas).

The ancient Roman family was a complex social structure, based mainly on the nuclear family, but also included various combinations of other members, such as extended family members, household slaves, and freed slaves. Ancient Romans had different names to describe their concepts of family, such as, "familia" to describe the nuclear family and "domus" which would have included all the inhabitants of the household. The types of interactions between the different members of the family were dictated by the perceived social roles each member played. An ancient Roman family's structure was constantly changing as a result of the low life expectancy and through marriage, divorce, and adoption.

Servilia was an ancient Roman woman who was the wife of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Minor, the son of the triumvir and Pontifex maximus Lepidus. She may also have been the same Servilia who was at one time engaged to Octavian.

In ancient Rome the dies lustricus was a traditional naming ceremony in which an infant was purified and given a praenomen. This occurred on the eighth day for girls and the ninth day for boys, a difference Plutarch explains by noting that "it is a fact that the female grows up, and attains maturity and perfection before the male." Until the umbilical cord fell off, typically on the seventh day, the baby was regarded as "more like a plant than an animal," as Plutarch expresses it. The ceremony of the dies lustricus was thus postponed until the last tangible connection to the mother's body was dissolved and the child was seen "as no longer forming part of the mother, and in this way as possessing an independent existence which justified its receiving a name of its own and therefore a fate of its own." The day was celebrated with a family feast. The childhood goddess Nundina presided over the event, and the goddess Nona was supposed to determine a person's lifespan. Prior to the ceremony infants were not considered part of the household, even if their father had raised them up during a tollere liberum.

In classical Islamic law, a concubine was an unmarried slave-woman with whom her master engaged in sexual relations with her consent. Concubinage was widely accepted by Muslim scholars in pre-modern times. Most modern Muslims, both scholars and laypersons, believe that Islam no longer permits concubinage and that sexual relations are religiously permissible only within marriage.

In ancient Rome, contubernium was a quasi-marital relationship between two slaves or between a slave (servus) and a free person who was usually a former slave or the child of a former slave. A slave involved in such a relationship was called contubernalis, the basic and general meaning of which was "companion".

References

- ↑ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2014). The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. OUP Oxford. pp. ?. ISBN 9780191016769.

- ↑ The Journal of Juristic Papyrology. Vol. 1. Warsaw Society of Sciences and Letters. 1952. p. 30.

- ↑ Bullettino dell'Istituto di diritto romano. Vol. 55–56. UC Southern Regional Library Facility: Giuffrè. 1951. p. 115.

- ↑ of Rievaulx, Aelred (2016). Pezzini, Domenico (ed.). The Liturgical Sermons: The Second Clairvaux Collection; Christmas through All Saints. Cistercian Fathers. Vol. 77. Translated by Mayeski, Marie Anne. Liturgical Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780879076917.

- ↑ The Journal of Juristic Papyrology. Vol. 1. Warsaw Society of Sciences and Letters. 1952. p. 31.

- ↑ Dixon, Suzanne (2005). Childhood, Class and Kin in the Roman World. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 9781134563197.

- ↑ Yoshida, Sarah Elise (2001). The Marriage of Roman soldiers (13 BC-AD 235), Law and Order in the Imperial Army. W Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition. Vol. 24. Brill. p. 315. ISBN 9789004121553.

- ↑ Wium Westrup, Carl (1944). Introduction to Early Roman Law: The house community. v.1. sect.1. Community of cult. University of Michigan: Levin & Munksgaard. p. 260.