In ancient Greek religion, Hera is the goddess of marriage, women, and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she is queen of the twelve Olympians and Mount Olympus, sister and wife of Zeus, and daughter of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. One of her defining characteristics in myth is her jealous and vengeful nature in dealing with any who offended her, especially Zeus's numerous adulterous lovers and illegitimate offspring.

Infanticide is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of resources being spent on weak or disabled offspring. Unwanted infants were usually abandoned to die of exposure, but in some societies they were deliberately killed. Infanticide is generally illegal, but in some places the practice is tolerated, or the prohibition is not strictly enforced.

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon, while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the valley of Evrotas river in Laconia, in southeastern Peloponnese. Around 650 BC, it rose to become the dominant military land-power in ancient Greece.

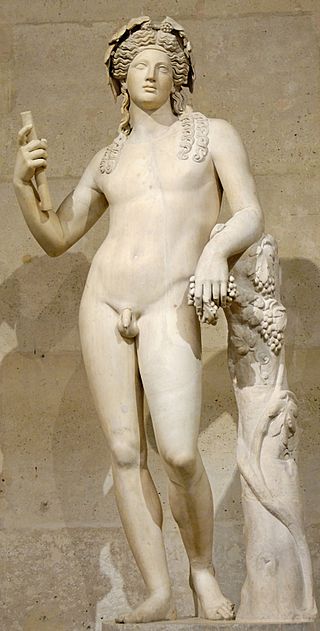

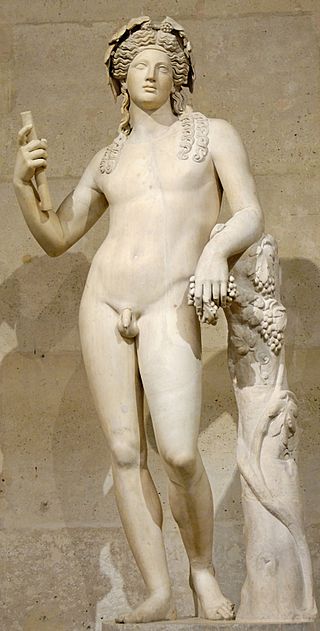

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus by the Greeks for a frenzy he is said to induce called baccheia. As Dionysus Eleutherius, his wine, music, and ecstatic dance free his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subvert the oppressive restraints of the powerful. His thyrsus, a fennel-stem sceptre, sometimes wound with ivy and dripping with honey, is both a beneficent wand and a weapon used to destroy those who oppose his cult and the freedoms he represents. Those who partake of his mysteries are believed to become possessed and empowered by the god himself.

In Greek mythology, Telephus was the son of Heracles and Auge, who was the daughter of king Aleus of Tegea. He was adopted by Teuthras, the king of Mysia, in Asia Minor, whom he succeeded as king. Telephus was wounded by Achilles when the Achaeans came to his kingdom on their way to sack Troy and bring Helen back to Sparta, and later healed by Achilles. He was the father of Eurypylus, who fought alongside the Trojans against the Greeks in the Trojan War. Telephus' story was popular in ancient Greek and Roman iconography and tragedy. Telephus' name and mythology were possibly derived from the Hittite god Telepinu.

Child abandonment is the practice of relinquishing interests and claims over one's offspring in an illegal way, with the intent of never resuming or reasserting guardianship. The phrase is typically used to describe the physical abandonment of a child. Still, it can also include severe cases of neglect and emotional abandonment, such as when parents fail to provide financial and emotional support for children over an extended period. An abandoned child is referred to as a foundling. Baby dumping refers to parents leaving a child younger than 12 months in a public or private place with the intent of terminating their care for the child. It is also known as rehoming when adoptive parents use illegal means, such as the internet, to find new homes for their children. In the case where child abandonment is anonymous within the first 12 months, it may be referred to as secret child abandonment.

In the field of political science, civics is the study of the civil and political rights and obligations of citizens in a society. The term civics derives from the Latin word civicus, meaning "relating to a citizen". In U.S. politics, in the context of urban planning, the term civics comprehends the city politics that affect the political decisions of the citizenry of a city.

The helots were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristics, such as whether they constituted an Ancient Greek tribe, a social class, or both. For example, Critias described helots as "slaves to the utmost", whereas according to Pollux, they occupied a status "between free men and slaves". Tied to the land, they primarily worked in agriculture as a majority and economically supported the Spartan citizens.

Harmodius and Aristogeiton were two lovers in Classical Athens who became known as the Tyrannicides for their assassination of Hipparchus, the brother of the tyrant Hippias, for which they were executed. A few years later, in 510 BC, the Spartan king Cleomenes I forced Hippias to go into exile, thereby opening the way to the subsequent democratic reforms of Cleisthenes. The Athenian democrats later celebrated Harmodius and Aristogeiton as national heroes, partially to conceal the role played by Sparta in the removal of the Athenian tyranny. Cleisthenes notably commissioned the famous statues of the Tyrannicides.

The Crypteia, also referred to as Krypteia or Krupteia, was an ancient Spartan state institution. The kryptai either principally sought out and killed helots across Laconia and Messenia as part of a policy of terrorising and intimidating the enslaved population, or they principally did a form of military training, or they principally endured hardships as an initiation ordeal, or the Crypteia served a combination of all these purposes, possibly varying over time. The Krypteia was an element of the Spartan state's child-rearing system for upper-class males.

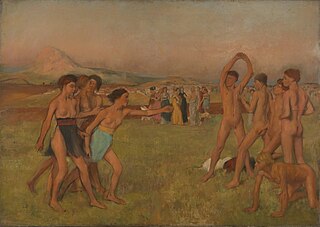

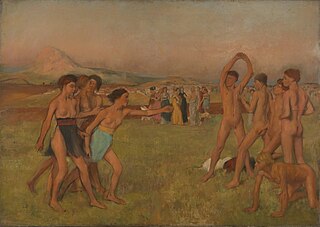

The agoge was the training program pre-requisite for Spartiate (citizen) status. Spartiate-class boys entered it age seven, and aged out at 30. It was considered violent by the standards of the day, and was sometimes fatal.

The family as a model for the organization of the state is a theory of political philosophy. It explains the structure of certain kinds of state in terms of the structure of the family, or it attempts to justify certain types of state by appeal to the structure of the family. The first known writer to use it was Aristotle, who argued that the natural progression of human beings was from the family via small communities to the polis.

Lycurgus was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its eunomia, involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The Spartans in the historical period honoured him as god.

In Greek mythology, Auge, was the daughter of Aleus the king of Tegea in Arcadia, and the virgin priestess of Athena Alea. She was also the mother of the hero Telephus by Heracles.

Neonaticide is the deliberate act of a parent murdering their own child during the first 24 hours of life. As a noun, the word "neonaticide" may also refer to anyone who practices or who has practiced this.

Education for Greek people was vastly "democratized" in the 5th century B.C., influenced by the Sophists, Plato, and Isocrates. Later, in the Hellenistic period of Ancient Greece, education in a gymn school was considered essential for participation in Greek culture. The value of physical education to the ancient Greeks and Romans has been historically unique. There were two forms of education in ancient Greece: formal and informal. Formal education was attained through attendance to a public school or was provided by a hired tutor. Informal education was provided by an unpaid teacher and occurred in a non-public setting. Education was an essential component of a person's identity.

Spartan women were famous in ancient Greece for seemingly having more freedom than women elsewhere in the Greek world. To contemporaries outside of Sparta, Spartan women had a reputation for promiscuity and controlling their husbands. Spartan women could legally own and inherit property, and they were usually better educated than their Athenian counterparts. The surviving written sources are limited and largely from a non-Spartan viewpoint. Anton Powell wrote that to say the written sources are "'not without problems'... as an understatement would be hard to beat".

In the earliest written sources, abortion is not considered as a general category of crime. Rather, specific kinds of abortion are prohibited, for various social and political reasons. In the earliest texts, it can be difficult to discern to what extent a particular religious injunction held force as secular law. In later texts, the rationale for abortion laws may be sought in a wide variety of fields including philosophy, religion, and jurisprudence. These rationales were not always included in the wording of the actual laws.

In Greek mythology, the name Arge may refer to:

China has a history of female infanticide which spans 2,000 years. When Christian missionaries arrived in China in the late sixteenth century, they witnessed newborns being thrown into rivers or onto rubbish piles. In the seventeenth century Matteo Ricci documented that the practice occurred in several of China's provinces and said that the primary reason for the practice was poverty. The practice continued into the 19th century and declined precipitously after the proclamation of the People's Republic of China, but reemerged as an issue after the PRC government introduced the one-child policy in the early 1980s. The 2020 census showed a male-to-female ratio of 105.07 to 100 for mainland China, a record low since the People's Republic of China (PRC) began conducting censuses. Every year in the PRC and India alone, there are close to two million instances of some form of female infanticide.