Related Research Articles

Edward Henry Weston was a 20th-century American photographer. He has been called "one of the most innovative and influential American photographers..." and "one of the masters of 20th century photography." Over the course of his 40-year career Weston photographed an increasingly expansive set of subjects, including landscapes, still-lifes, nudes, portraits, genre scenes and even whimsical parodies. It is said that he developed a "quintessentially American, and especially Californian, approach to modern photography" because of his focus on the people and places of the American West. In 1937 Weston was the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, and over the next two years he produced nearly 1,400 negatives using his 8 × 10 view camera. Some of his most famous photographs were taken of the trees and rocks at Point Lobos, California, near where he lived for many years.

William Eugene Smith was an American photojournalist. He has been described as "perhaps the single most important American photographer in the development of the editorial photo essay." His major photo essays include World War II photographs, the visual stories of an American country doctor and a nurse midwife, the clinic of Albert Schweitzer in French Equatorial Africa, the city of Pittsburgh, and the pollution which damaged the health of the residents of Minamata in Japan. His 1948 series, Country Doctor, photographed for Life, is now recognized as "the first extended editorial photo story".

Edward Jean Steichen was a Luxembourgish American photographer, painter, and curator, renowned as one of the most prolific and influential figures in the history of photography.

The Family of Man was an ambitious exhibition of 503 photographs from 68 countries curated by Edward Steichen, the director of the New York City Museum of Modern Art's (MoMA) Department of Photography. According to Steichen, the exhibition represented the "culmination of his career." The title was taken from a line in a Carl Sandburg poem.

Wynn Bullock was an American photographer whose work is included in over 90 major museum collections around the world. He received substantial critical acclaim during his lifetime, published numerous books and is mentioned in all the standard histories of modern photography.

Herbert List was a German photographer, who worked for magazines, including Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, and Life, and was associated with Magnum Photos. His austere, classically posed black-and-white compositions, particularly his homoerotic male nudes, taken in Italy and Greece being influential in modern photography and contemporary fashion photography.

Bruce Landon Davidson is an American photographer. He has been a member of the Magnum Photos agency since 1958. His photographs, notably those taken in Harlem, New York City, have been widely exhibited and published. He is known for photographing communities usually hostile to outsiders.

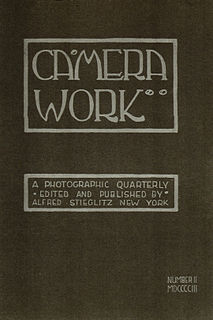

Camera Work was a quarterly photographic journal published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917. It is known for its many high-quality photogravures by some of the most important photographers in the world and its editorial purpose to establish photography as a fine art. It has been called "consummately intellectual", "by far the most beautiful of all photographic magazines", and "a portrait of an age [in which] the artistic sensibility of the nineteenth century was transformed into the artistic awareness of the present day."

Louis Faurer was an American candid or street photographer. He was a quiet artist who never achieved the broad public recognition that his best-known contemporaries did; however, the significance and caliber of his work were lauded by insiders, among them Robert Frank, William Eggleston, and Edward Steichen, who included his work in the Museum of Modern Art exhibitions In and Out of Focus (1948) and The Family of Man (1955).

Wayne Forest Miller was an American photographer known for his series of photographs The Way of Life of the Northern Negro. Active as a photographer from 1942 until 1975, he was a contributor to Magnum Photos beginning in 1958.

J.R. Wharton Eyerman was an American photographer and photojournalist.

Leon Levinstein (1910–1988) was an American street photographer best known for his work documenting everyday street life in New York City from the 1950s through the 1980s. In 1975 Levinstein was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Humanist Photography, also known as the School of Humanist Photography, manifests the Enlightenment philosophical system in social documentary practice based on a perception of social change. It emerged in the mid-twentieth-century and is associated most strongly with Europe, particularly France, where the upheavals of the two world wars originated, though it was a worldwide movement. It can be distinguished from photojournalism, with which it forms a sub-class of reportage, as it is concerned more broadly with everyday human experience, to witness mannerisms and customs, than with newsworthy events, though practitioners are conscious of conveying particular conditions and social trends, often, but not exclusively, concentrating on the underclasses or those disadvantaged by conflict, economic hardship or prejudice. Humanist photography "affirms the idea of a universal underlying human nature". Jean Claude Gautrand describes humanist photography as:

a lyrical trend, warm, fervent, and responsive to the sufferings of humanity [which] began to assert itself during the 1950s in Europe, particularly in France ... photographers dreamed of a world of mutual succour and compassion, encapsulated ideally in a solicitous vision.

Willi (Willie) Huttig was a German photographer and alpinist.

Margery Lewis (Smith) was an American photographer active from the 1940s to the 1970s.

William Vandivert was an American photographer, co-founder in 1947 of the agency Magnum Photos.

Edward Wallowitch was an American art photographer who at age 17 had three prints in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the youngest photographer to be so honored, and who collaborated with Andy Warhol. He was active from the 1940s to the 1970s.

Inge Pål-Nils Nilsson, was a Swedish photographer and filmmaker active from the 1950s to the 1990s.

John Bertolino was an American photojournalist who photographed in Italy and the United States and was active in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sam Falk was an early- and mid-twentieth-century American photojournalist who worked for The New York Times from 1925 to 1969, and wrote and photographed for other publications.

References

- ↑ LIFE, 8 May 1939, page 12, Vol. 6, No. 19, ISSN 0024-3019, Published by Time Inc

- ↑ US patent 2,029,238 Camera Mechanism, Application June 4, 1933

- ↑ US patent 2,323,473 All-Metal Folding Camera Stand, filed May 6, 1941

- ↑ US patent 4,341,452 (45) Jul. 27, 1982

- ↑ Steichen, Edward; Sandburg, Carl; Norman, Dorothy; Lionni, Leo; Mason, Jerry; Stoller, Ezra; Museum of Modern Art (New York) (1955). The family of man: The photographic exhibition. Published for the Museum of Modern Art by Simon and Schuster in collaboration with the Maco Magazine Corporation.

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3

{{citation}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Sandeen, Eric J (1995), Picturing an exhibition : the family of man and 1950s America (1st ed.), University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 978-0-8263-1558-8

- ↑ Abigail Foerstner ‘Torkel Korling's `Art Of Commerce' Shows Classic Work’ Chicago Tribune February 4, 1994

- ↑ Imaging the Craft: Photography in the R.R. Donnelley Archive in the University of Chicago Library Special Collections Research Center

- ↑ Photo-era Magazine, Volume 67, p.231, A.H. Beardsley, 1931

- ↑ Popular Photography, Feb 1946, Vol. 18, No. 2, page 65

- 1 2 Anthony Burke Boylan 'Torkel Korling; Photos Won Lasting Recognition', Chicago Tribune, October 27, 1998

- ↑ Korling, Torkel; Voss, Edward G. (Edward Groesbeck), 1929- (1973), The boreal forest and borders, from nature, Dundee, Ill

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)