Related Research Articles

A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Individual cultures have their own names, in their respective Indigenous languages, for the spiritual healers and ceremonial leaders in their particular cultures.

A sweat lodge is a low profile hut, typically dome-shaped or oblong, and made with natural materials. The structure is the lodge, and the ceremony performed within the structure may be called by some cultures a purification ceremony or simply a sweat. Traditionally the structure is simple, constructed of saplings covered with blankets and sometimes animal skins. Originally, it was only used by some of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, notably the Plains Indians, but with the rise of pan-Indianism, numerous nations that did not originally have the sweat lodge ceremony have adopted it. This has been controversial.

Plenty Coups was the principal chief of the Crow Nation ("Apsáalooke") and a visionary leader.

Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation is one of seven Native American reservations in the U.S. state of Montana. Established by an act of Congress on September 7, 1916, it was named after Ahsiniiwin, the chief of the Chippewa band, who had died a few months earlier. It was established for landless Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians in the American West, but within a short period of time many Cree (Nēhiyaw) and Métis were also settled there. Today the Cree outnumber the Chippewa on the reservation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) recognizes it as the Chippewa Cree Reservation.

To some indigenous peoples of North America, the medicine wheel is a metaphor for a variety of spiritual concepts. A medicine wheel may also be a stone monument that illustrates this metaphor.

The Blackfeet Nation, officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Montana. Tribal members primarily belong to the Piegan Blackfeet band of the larger Blackfoot Confederacy that spans Canada and the United States.

Joseph Medicine Crow was a Native American writer, historian and war chief of the Crow Nation. His writings on Native American history and reservation culture are considered seminal works, but he is best known for his writings and lectures concerning the Battle of the Little Bighorn of 1876.

The Jeffers Petroglyphs site is an outcrop in southwestern Minnesota with pre-contact Native American petroglyphs. The petroglyphs are pecked into rock of the Red Rock Ridge, a 23-mile (37 km)-long Sioux quartzite outcrop that extends from Watonwan County, Minnesota to Brown County, Minnesota. The exposed surface is approximately 150 by 650 feet and surrounded by virgin prairie. "The site lies in an area inhabited in the early historic period by the Dakota Indians, and both the style and form of some of the carvings are identical with motifs that appear on Dakota hide paintings and their quill designs and beadwork. Others are foreign to this Plains Indian tradition and seem to be much earlier in origin." Several old wagon trail ruts traverse the site, one of which is believed to be the old stage coach route from New Ulm, Minnesota to Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individuals make personal sacrifices on behalf of the community.

The Gros Ventre, also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are enrolled in the Fort Belknap Indian Community of the Fort Belknap Reservation of Montana, a federally recognized tribe with 3,682 enrolled members, that also includes Assiniboine people or Nakoda people, the Gros Ventre's historical enemies. The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation is in the northernmost part of Montana, just south of the small town of Harlem, Montana. Chiefs: The Belly Government Council

Plastic shaman, or plastic medicine people, is a pejorative colloquialism applied to individuals who are attempting to pass themselves off as shamans, holy people, or other traditional spiritual leaders, but who have no genuine connection to the traditions or cultures they claim to represent. In some cases, the "plastic shaman" may have some genuine cultural connection, but is seen to be exploiting that knowledge for ego, power, or money.

Smudging, or other rites involving the burning of sacred herbs or resins, is a ceremony practiced by some Indigenous peoples of the Americas. While it bears some resemblance to other ceremonies and rituals involving smoke from other world cultures, notably those that use smoke for spiritual cleansing or blessing, the purposes and particulars of the ceremonies, and the substances used, can vary widely between tribes, bands and nations, and even more so between different world cultures. In traditional communities, Elders maintain the protocols around these ceremonies and provide culturally specific guidance. The smudging ceremony, by various names, has been appropriated by others outside of the Indigenous communities as part of New Age or commercial practices, which has also led to the over-harvesting of some of the plants used in ceremonies. The appropriation and the over-harvesting have both been protested by Indigenous people in the US and Canada.

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately 690 square miles (1,800 km2) in size and home to approximately 5,000 Cheyenne people. The tribal and government headquarters are located in Lame Deer, also the home of the annual Northern Cheyenne pow wow.

Oren R. Lyons Jr. is a Native American Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan. The Seneca are one of the Six Nations of the historic Haudenosaunee Confederacy. For more than 14 years he has been a member of the Indigenous Peoples of the Human Rights Commission of the United Nations, and has had other leadership roles.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act, Public Law No. 95–341, 92 Stat. 469, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1996, is a United States federal law, enacted by joint resolution of the Congress in 1978. Prior to the act, many aspects of Native American religions and sacred ceremonies had been prohibited by law.

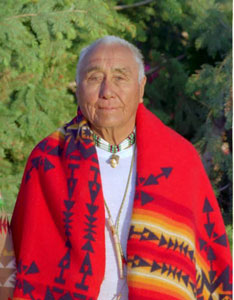

Thomas Yellowtail was a Medicine Man and Sun Dance chief of the Crow tribe for over thirty years prior to his death. Thomas Yellowtail's adult life was dedicated to the adherence to, and preservation of, the Sun Dance religion.

William Commanda OC was an Algonquin elder, spiritual leader, and promoter of environmental stewardship. Commanda served as Band Chief of the Kitigàn-zìbì Anishinàbeg First Nation near Maniwaki, Quebec, from 1951 to 1970. In his life, he worked as a guide, a trapper and woodsman, and was a skilled craftsman and artisan who excelled at constructing birch bark canoes. He was Keeper of several Algonquin wampum shell belts, which held records of prophecies, history, treaties and agreements. In 2008, Commanda was appointed to the rank of officer of the Order of Canada.

Native American religions are the spiritual practices of the Native Americans in the United States. Ceremonial ways can vary widely and are based on the differing histories and beliefs of individual nations, tribes and bands. Early European explorers describe individual Native American tribes and even small bands as each having their own religious practices. Theology may be monotheistic, polytheistic, henotheistic, animistic, shamanistic, pantheistic or any combination thereof, among others. Traditional beliefs are usually passed down in the forms of oral histories, stories, allegories, and principles.

Gladys Iola Tantaquidgeon was a Mohegan medicine woman, anthropologist, author, tribal council member, and elder based in Connecticut.

The Association on American Indian Affairs is a nonprofit human rights charity located in Rockville, Maryland. Founded in 1922, it is dedicated to protecting the rights of Native Americans.

References

- 1 2 Vander Puy, Nick (August 8, 2004). "Traditional Elder and Youth Circle was true spiritual offering". News from Indian Country. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ↑ Brown, Trish. "200 Attend Traditional Circle of Indian Elders and Youth Conference". Tribal Observer. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- 1 2 Costello, Rebecca (2011). "Young runner for the circle: Eric Noyes '86 has a calling: to help American Indians preserve their traditions and spread their message". Scene, the Online Magazine for the Colgate Community. No. Autumn. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ Kopchick, Kathryn (2011-04-11). "Chief Oren Lyons to discuss 'An Iroquois View'". Bucknell University. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Oren Lyons". Americans Who Tell The Truth: Models of Courageous Citizenship. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ Talbot, Steve (Fall 2006). "Spiritual Genocide: The Denial of American Indian Religious Freedom, from Conquest to 1934". Wíčazo Ša Review. 21 (2): 7–39. doi:10.1353/wic.2006.0024. ISSN 0749-6427. Online version: ISSN 1533-7901

- ↑ Gobert, Trina (June 1, 2000). "Preserving the wisdom (Native film maker Danny Beaton records Native elders)". Wind Speaker. Retrieved 2009-11-06.