Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

The integumentary system is the set of organs forming the outermost layer of an animal's body. It comprises the skin and its appendages, which act as a physical barrier between the external environment and the internal environment that it serves to protect and maintain the body of the animal. Mainly it is the body's outer skin.

Keratinocytes are the primary type of cell found in the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. In humans, they constitute 90% of epidermal skin cells. Basal cells in the basal layer of the skin are sometimes referred to as basal keratinocytes. Keratinocytes form a barrier against environmental damage by heat, UV radiation, water loss, pathogenic bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses. A number of structural proteins, enzymes, lipids, and antimicrobial peptides contribute to maintain the important barrier function of the skin. Keratinocytes differentiate from epidermal stem cells in the lower part of the epidermis and migrate towards the surface, finally becoming corneocytes and eventually be shed off, which happens every 40 to 56 days in humans.

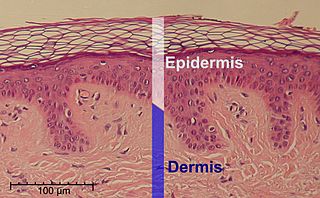

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water released from the body into the atmosphere through transepidermal water loss.

A skin condition, also known as cutaneous condition, is any medical condition that affects the integumentary system—the organ system that encloses the body and includes skin, nails, and related muscle and glands. The major function of this system is as a barrier against the external environment.

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis. The human stratum corneum comprises several levels of flattened corneocytes that are divided into two layers: the stratum disjunctum and stratum compactum. The skin's protective acid mantle and lipid barrier sit on top of the stratum disjunctum. The stratum disjunctum is the uppermost and loosest layer of skin. The stratum compactum is the comparatively deeper, more compacted and more cohesive part of the stratum corneum. The corneocytes of the stratum disjunctum are larger, more rigid and more hydrophobic than that of the stratum compactum.

Crocodile armor consists of the protective dermal and epidermal components of the integumentary system in animals of the order Crocodilia.

A moisturizer, or emollient, is a cosmetic preparation used for protecting, moisturizing, and lubricating the skin. These functions are normally performed by sebum produced by healthy skin. The word "emollient" is derived from the Latin verb mollire, to soften.

Desquamation occurs when the outermost layer of a tissue, such as the skin, is shed. The term is from Latin desquamare 'to scrape the scales off a fish'.

Hyperkeratosis is thickening of the stratum corneum, often associated with the presence of an abnormal quantity of keratin, and also usually accompanied by an increase in the granular layer. As the corneum layer normally varies greatly in thickness in different sites, some experience is needed to assess minor degrees of hyperkeratosis.

Diprobase is an emollient, specifically targeted at eczema and dermatitis. It is an occlusive emollient, meaning that it restores the layer of oil on the surface of the skin to slow water loss. This gives its tendency to make the applied area sticky.

The stratum lucidum is a thin, clear layer of dead skin cells in the epidermis named for its translucent appearance under a microscope. It is readily visible by light microscopy only in areas of thick skin, which are found on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet.

A stratified squamous epithelium consists of squamous (flattened) epithelial cells arranged in layers upon a basal membrane. Only one layer is in contact with the basement membrane; the other layers adhere to one another to maintain structural integrity. Although this epithelium is referred to as squamous, many cells within the layers may not be flattened; this is due to the convention of naming epithelia according to the cell type at the surface. In the deeper layers, the cells may be columnar or cuboidal. There are no intercellular spaces. This type of epithelium is well suited to areas in the body subject to constant abrasion, as the thickest layers can be sequentially sloughed off and replaced before the basement membrane is exposed. It forms the outermost layer of the skin and the inner lining of the mouth, esophagus and vagina.

The human skin is the outer covering of the body and is the largest organ of the integumentary system. The skin has up to seven layers of ectodermal tissue guarding muscles, bones, ligaments and internal organs. Human skin is similar to most of the other mammals' skin, and it is very similar to pig skin. Though nearly all human skin is covered with hair follicles, it can appear hairless. There are two general types of skin, hairy and glabrous skin (hairless). The adjective cutaneous literally means "of the skin".

Transdermal is a route of administration wherein active ingredients are delivered across the skin for systemic distribution. Examples include transdermal patches used for medicine delivery. The drug is administered in the form of a patch or ointment that delivers the drug into the circulation for systemic effect.

Corneocytes are terminally differentiated keratinocytes and compose most of the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the epidermis. They are regularly replaced through desquamation and renewal from lower epidermal layers and are essential for its function as a skin barrier.

Keratohyalin is a protein structure found in cytoplasmic granules of the keratinocytes in the stratum granulosum of the epidermis. Keratohyalin granules (KHG) mainly consist of keratin, profilaggrin, loricrin and trichohyalin proteins which contribute to cornification or keratinization, the process of the formation of epidermal cornified cell envelope. During the keratinocyte differentiation, these granules maturate and expand in size, which leads to the conversion of keratin tonofilaments into a homogenous keratin matrix, an important step in cornification.

Bullous impetigo is a bacterial skin infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus that results in the formation of large blisters called bullae, usually in areas with skin folds like the armpit, groin, between the fingers or toes, beneath the breast, and between the buttocks. It accounts for 30% of cases of impetigo, the other 70% being non-bullous impetigo.

Skin sloughing is the process of shedding dead surface cells from the skin. It is most associated with cosmetic skin maintenance via exfoliation, but can also occur biologically or for medical reasons.

TGM5 is a transglutaminase enzyme.