The Treaty of Canterbury was a diplomatic agreement concluded between Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, and King Henry V of England on 15 August 1416. The treaty resulted in a defensive and offensive alliance against France.

The Treaty of Canterbury was a diplomatic agreement concluded between Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, and King Henry V of England on 15 August 1416. The treaty resulted in a defensive and offensive alliance against France.

Sigismund began to shift his alliance from France to England after the French defeat at the Battle of Agincourt. After departing from the Council of Constance, Sigismund arrived in Paris on 1 March 1416. He was unable to reach an agreement with the French government because Bernard d'Armagnac wanted to maintain his naval blockade of Harfleur and prevent the English from maintaining a naval base in Normandy. In addition, Sigismund could not create an agreement that satisfied both the opposing Orleanist and Burgundian factions of the government.

As a result of his struggles in creating an agreement, Sigismund travelled to London on 3 May 1416 to negotiate with Henry V of England. Upon his arrival, Sigismund was made a Knight of the Garter, viewed a session of parliament and was gifted a golden necklace that was created by Hermann Ruissel and featured white enamel bears, one of Henry's heraldic devices. [1] However, Sigismund still wanted a peace settlement and continued negotiating with France as well. In July 1416, Sigismund convinced Henry V and the French government to hold a conference in Paris between Charles VI of France, Sigismund and Henry V to discuss a possible peace treaty.

However, Bernard of Armagnac, having lost the Battle of Valmont in 1416, convinced Charles VI and the French government to reject the embassy because he believed that it was just a scheme that would result in the English gaining the territory of Harfleur. Angered by the rejection, Sigismund resorted to creating the Treaty of Canterbury with only England, on the grounds that France favoured the schism and opposed any peace agreement with England. [2]

Sigismund wanted to unify the Catholic Church and end the Papal schism. However, he believed that the tensions between the English and the French served as a major obstacle to accomplishing unification. In addition, Sigismund desired to create a united Europe to fight in a crusade against the Ottoman Empire. [2]

The treaty was signed on 15 August 1416. Henry V and Sigismund pledged to each other that they would provide support to gain back any territories held by the French. The subjects of both rulers were given the ability to trade and move among each other's lands freely. They agreed that neither side would harbor traitors or rebels of the other but would aid each other during an invasion. [2]

The Treaty of Canterbury, by favoring England and denouncing France, effectively ended the friendship between the house of Luxembourg and France, which Sigismund's grandfather, John of Bohemia, had established. [3] However, before the end of Henry V's reign, the policies established by the Treaty of Canterbury had been abandoned because Sigismund became more involved in the Council of Constance and his control over Bohemian territory and less concerned with Anglo-French politics. All of those distractions meant that Sigismund was never able to create any military support and that the true intent of the treaty was not fulfilled. [2]

The Council of Constance was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church that was held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance (Konstanz) in present-day Germany. This was the first time that an ecumenical council was convened in the Holy Roman Empire. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the resignation of the remaining papal claimants and by electing Pope Martin V. It was the last papal election to take place outside of Italy.

The 12th century is the period from 1101 to 1200 in accordance with the Julian calendar. In the history of European culture, this period is considered part of the High Middle Ages and overlaps with what is often called the "'Golden Age' of the Cistercians". The Golden Age of Islam experienced significant development, particularly in Islamic Spain.

The 1370s was a decade of the Julian Calendar which began on January 1, 1370, and ended on December 31, 1379.

Sigismund of Luxembourg was Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 until his death in 1437. He was elected King of Germany in 1410, and was also King of Bohemia from 1419, as well as prince-elector of Brandenburg. As the husband of Mary, Queen of Hungary, he was also King of Hungary and Croatia from 1387. He was the last male member of the House of Luxembourg.

Henry V, also called Henry of Monmouth, was King of England from 1413 until his death in 1422. Despite his relatively short reign, Henry's outstanding military successes in the Hundred Years' War against France made England one of the strongest military powers in Europe. Immortalised in Shakespeare's "Henriad" plays, Henry is known and celebrated as one of the greatest warrior-kings of medieval England.

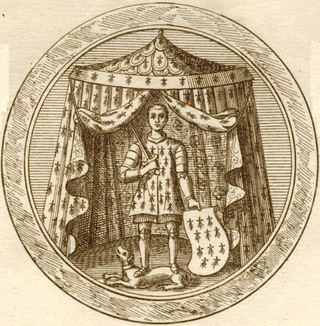

John V, sometimes numbered as VI, bynamed John the Wise, was Duke of Brittany and Count of Montfort from 1399 to his death. His rule coincided with the height of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. John's reversals in that conflict, as well as in other internal struggles in France, served to strengthen his duchy and to maintain its independence.

Jacqueline, of the House of Wittelsbach, was a noblewoman who ruled the counties of Holland, Zeeland and Hainaut in the Low Countries from 1417 to 1433. She was also Dauphine of France for a short time between 1415 and 1417 and Duchess of Gloucester in the 1420s, if her marriage to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, is accepted as valid.

Ernest the Iron-Willed, a member of the House of Habsburg, ruled over the Inner Austrian duchies of Styria, Carinthia and Carniola from 1406 until his death. He was head of the Habsburg Leopoldian line from 1411.

The Lancastrian War was the third and final phase of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. It lasted from 1415, when Henry V of England invaded Normandy, to 1453, when the English were definitively defeated in Aquitaine. It followed a long period of peace from the end of the Caroline War in 1389. The phase is named after the House of Lancaster, the ruling house of the Kingdom of England, to which Henry V belonged.

Events from the 1370s in England.

Events from the 1440s in England.

The dual monarchy of England and France existed during the latter phase of the Hundred Years' War when Charles VII of France and Henry VI of England disputed the succession to the throne of France. It commenced on 21 October 1422 upon the death of King Charles VI of France, who had signed the Treaty of Troyes which gave the French crown to his son-in-law Henry V of England and Henry's heirs. It excluded King Charles's son, the Dauphin Charles, who by right of primogeniture was the heir to the Kingdom of France. Although the Treaty was ratified by the Estates-General of France, the act was a contravention of the French law of succession which decreed that the French crown could not be alienated. Henry VI, son of Henry V, became king of both England and France and was recognized only by the English and Burgundians until 1435 as King Henry II of France. He was crowned King of France on 16 December 1431 in Paris.

The War of the Jülich Succession, also known as the Jülich War or the Jülich-Cleves Succession Crises, was a war of succession in the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. The first phase of the war lasted between 10 June 1609 and 24 October 1610, with the second phase starting in May 1614 and finally ending on 13 October 1614. At first, the war pitted Catholic Archduke Leopold V against the combined forces of the Protestant claimants, Johann Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg and Wolfgang Wilhelm of Palatinate-Neuburg, ending in the former's military defeat. The representatives of Brandenburg and Neuburg later entered conflict amongst themselves, partly due to religious conversions, which led to the resumption of hostilities.

The Treaty of Amiens, signed on 13 April 1423, was a defensive agreement between Burgundy, Brittany, and England during the Hundred Years' War. The English were represented by John, Duke of Bedford, the English regent of France, the Burgundians by Duke Philip the Good himself, and the Bretons by Arthur de Richemont, on behalf of his brother the Duke of Brittany. By the agreement, all three parties acknowledged Henry VI of England as King of France, and agreed to aid each other against the Valois claimant, Charles VII. It also stipulated the marriage of Bedford and Richemont to Burgundy's sisters, in order to cement the alliance.

The Truce of Leulinghem was a truce agreed to by Richard II's kingdom of England and its allies, and Charles VI's kingdom of France and its allies, on 18 July 1389, ending the Caroline War of the Hundred Years' War. England was on the edge of financial collapse and suffering from internal political divisions. On the other side, Charles VI was suffering from a mental illness that handicapped the furthering of the war by the French government. Neither side was willing to concede on the primary cause of the war, the legal status of the Duchy of Aquitaine and the King of England's homage to the King of France through his possession of the duchy. However, both sides faced major internal issues that could badly damage their kingdoms if the war continued. The truce was originally negotiated by representatives of the kings to last three years, but the two kings met in person at Leulinghem, near the English fortress of Calais, and agreed to extend the truce to a twenty-seven years' period. Other provisions were agreed to, in attempts to bring an end to the Papal schism, to launch a joint crusade against the Turks in the Balkans, to seal the marriage of Richard to Charles' daughter Isabella along with an 800,000 franc dowry, and to guarantee to continue peace negotiations, in order to establish a lasting treaty between the kingdoms. The treaty brought peace to the Iberian Peninsula, where Portugal and Castile were supporting the English and French respectively. The English evacuated all their holdings in northern France except Calais.

The Triple Alliance of 1596, was an alliance between England, France and the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. The Republic joined as a third party to an earlier agreement between England and France, but the alliance did in fact not take effect until the Republic joined. By signing the treaty, France and England were the first states to recognize the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands as an independent state. The three parties in the alliance were all at war with Spain. There had been attempts to convince magnates from the Holy Roman Empire to join the alliance, but they did not want to enter the war against Spain. The alliance, along with other things, agreed to help maintain their respective armies. The alliance was in effect for only a few years.

Events from the year 1416 in France.

Treaty of Canterbury can refer to:

The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in April 1559 ended the Italian Wars (1494–1559). It consisted of two separate treaties, one between England and France on 2 April, and another between France and Spain on 3 April. Although he was not a signatory, both were approved by Emperor Ferdinand I, since many of the territorial exchanges concerned states within the Holy Roman Empire.

The Treaty of Dortmund, or Dortmund Recess, was an agreement that was concluded on 10 June 1609 between representatives of Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg and Wolfgang Wilhelm of Palatinate-Neuburg with regard to the succession of the United Duchies of Julich-Cleves-Berg through the mediation of Landgrave Maurice of Hesse-Kassel. It took place in the city of Dortmund.

treaty of canterbury