Charles I was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649.

George III was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Great Britain and Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with George as its king. He was concurrently Duke and Prince-elector of Hanover in the Holy Roman Empire before becoming King of Hanover on 12 October 1814. He was a monarch of the House of Hanover, who, unlike his two predecessors, was born in Great Britain, spoke English as his first language, and never visited Hanover.

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days' rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against British Catholics enacted by the Popery Act 1698. Lord George Gordon, head of the Protestant Association, argued that the law would enable Catholics to join the British Army and plot treason. The protest led to widespread rioting and looting, including attacks on Newgate Prison and the Bank of England and was the most destructive in the history of London.

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury PC, FRS, was an English statesman and peer. He held senior political office under both the Commonwealth of England and Charles II, serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1661 to 1672 and Lord Chancellor from 1672 to 1673. During the Exclusion Crisis, Shaftesbury headed the movement to bar the Catholic heir, James II, from the royal succession, which is often seen as the origin of the Whig party. He was also a patron of the political philosopher John Locke, with whom Shaftesbury collaborated with in writing the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina in 1669.

Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine, was a British Whig lawyer and politician. He served as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain between 1806 and 1807 in the Ministry of All the Talents.

Lloyd Kenyon, 1st Baron Kenyon,, was a British politician and barrister, who served as Attorney General, Master of the Rolls and Lord Chief Justice. Born to a country gentleman, he was initially educated in Hanmer before moving to Ruthin School aged 12. Rather than going to university he instead worked as a clerk to an attorney, joining the Middle Temple in 1750 and being called to the Bar in 1756. Initially almost unemployed due to the lack of education and contacts which a university education would have provided, his business increased thanks to his friendships with John Dunning, who, overwhelmed with cases, allowed Kenyon to work many, and Lord Thurlow who secured for him the Chief Justiceship of Chester in 1780. He was returned as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Hindon the same year, serving repeatedly as Attorney General under William Pitt the Younger. He effectively sacrificed his political career in 1784 to challenge the ballot of Charles James Fox, and was rewarded with a baronetcy; from then on he did not speak in the House of Commons, despite remaining an MP.

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws. Requirements to abjure (renounce) the temporal and spiritual authority of the pope and transubstantiation placed major burdens on Roman Catholics.

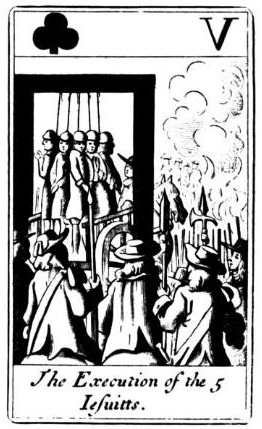

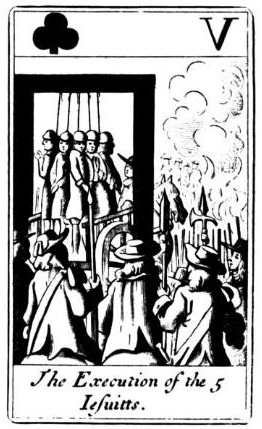

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II, accusations that led to the show trials and executions of at least 22 men and precipitated the Exclusion Bill Crisis. During this tumultuous period, Oates weaved an intricate web of accusations, fueling public fears and paranoia. However, as time went on, the lack of substantial evidence and inconsistencies in Oates's testimony began to unravel the plot. Eventually, Oates himself was arrested and convicted for perjury, exposing the fabricated nature of the conspiracy.

Lord George Gordon was a British nobleman and politician best known for lending his name to the Gordon Riots of 1780. An eccentric and flighty personality, he was born into the Scottish nobility and sat in the House of Commons from 1774 to 1780. His life ended after a number of controversies, notably one surrounding his conversion to Judaism, for which he was ostracised. He died in Newgate Prison.

The Papists Act 1778, also known as Sir George Savile's Act, the First Relief Act, or the Catholic Relief Act 1778 is an act of the Parliament of Great Britain and was the first Act for Roman Catholic relief. Later in 1778 it was also enacted by the Parliament of Ireland as the Leases for Lives Act 1777, also known as Gardiner's Act or the Catholic Relief Act 1777.

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall. In a repudiation of the government's policies, they were acquitted by three separate juries in November 1794 to public rejoicing. The treason trials were an extension of the sedition trials of 1792 and 1793 against parliamentary reformers in both England and Scotland.

Sir William Garrow, was an English barrister, politician and judge known for his indirect reform of the advocacy system, which helped usher in the adversarial court system used in most common law nations today. He introduced the phrase "presumed innocent until proven guilty", insisting that defendants' accusers and their evidence be thoroughly tested in court. Born to a priest and his wife in Monken Hadley, then in Middlesex, Garrow was educated at his father's school in the village before being apprenticed to Thomas Southouse, an attorney in Cheapside, which preceded a pupillage with Mr. Crompton, a special pleader. A dedicated student of the law, Garrow frequently observed cases at the Old Bailey; as a result Crompton recommended that he become a solicitor or barrister. Garrow joined Lincoln's Inn in November 1778, and was called to the Bar on 27 November 1783. He quickly established himself as a criminal defence counsel, and in February 1793 was made a King's Counsel by HM Government to prosecute cases involving treason and felonies.

Maurus Corker was an English Benedictine who was falsely accused and imprisoned as a result of the fabricated Popish Plot, but was acquitted of treason and eventually released.

The Roman Catholic relief bills were a series of measures introduced over time in the late 18th and early 19th centuries before the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom to remove the restrictions and prohibitions imposed on British and Irish Catholics during the English Reformation. These restrictions had been introduced to enforce the separation of the English church from the Catholic Church which began in 1529 under Henry VIII.

Stephen College was baptised as Stephen Golledge in Hertfordshire (1637–1681) was an English joiner, activist Protestant, and supporter of the perjury underlying the fabricated Popish Plot. He was tried and executed for high treason, on somewhat dubious evidence, in 1681.

An act against Jesuits, seminary priests, and such other like disobedient persons, also known as the Jesuits, etc. Act 1584, was an Act of the Parliament of England passed during the English Reformation. The Act commanded all Roman Catholic priests to leave the country within 40 days or they would be punished for high treason, unless within the 40 days, they swore an oath to obey the Queen. Those who harboured them, and all those who knew of their presence and failed to inform the authorities, would be fined and imprisoned for felony, or if the authorities wished to make an example of them, they might be executed for treason.

R v Baillie, also known as the Greenwich Hospital Case, was a 1778 prosecution of Thomas Baillie for criminal libel. The case initiated the legal career of Thomas Erskine. Baillie, the Lieutenant-Governor of the Greenwich Hospital for Seamen, a facility for injured or pensioned off seamen, had noted irregularities and corruption in the hospital, which was formally run by the Earl of Sandwich. After his official reporting of the problems failed to bring about reform in the hospital, Baillie published a pamphlet that was critical of the hospital's officers, alleging that Sandwich had given appointments to pay off political debts; Sandwich ignored the pamphlet but ensured that Baillie was indicted for criminal libel. Baillie hired five barristers, including Erskine, then newly called to the Bar, and appeared before Lord Mansfield in the Court of King's Bench on 23 November 1778.

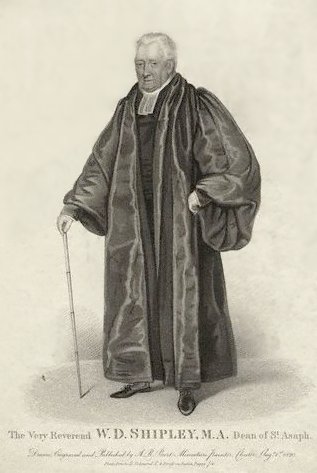

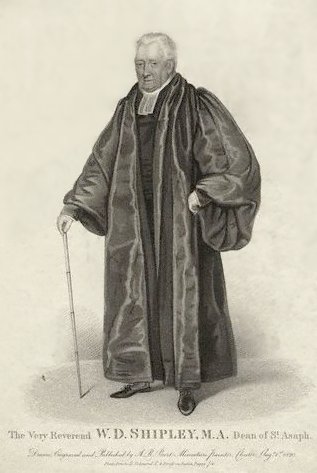

The Case of the Dean of St Asaph, formally R v Shipley, was the 1784 trial of William Davies Shipley, the Dean of St Asaph, for seditious libel. In the aftermath of the American War of Independence, electoral reform had become a substantial issue, and William Pitt the Younger attempted to bring a Bill before Parliament to reform the electoral system. In its support Shipley republished a pamphlet written by his brother-in-law, Sir William Jones, which noted the defects of the existing system and argued in support of Pitt's reforms. Thomas FitzMaurice, the brother of British Prime Minister Earl of Shelburne, reacted by indicting Shipley for seditious libel, a criminal offence which acted as "the government's chief weapon against criticism", since merely publishing something that an individual judge interpreted as libel was enough for a conviction; a jury was prohibited from deciding whether the material was actually libellous. The law was widely seen as unfair, and a Society for Constitutional Information was formed to pay Shipley's legal fees. With financial backing from the society Shipley was able to secure the services of Thomas Erskine KC as his barrister.

The Court of Castle Chamber was an Irish court of special jurisdiction which operated in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The trial of Thomas Paine for seditious libel was held on 18 December 1792 in response to his publication of the second part of the Rights of Man. The government of William Pitt, worried by the possibility that the French Revolution might spread to England, had begun suppressing works that espoused radical philosophies.