Related Research Articles

Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned from 578 to 535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Rome's first Etruscan king, who was assassinated in 579 BC. The constitutional basis for his accession is unclear; he is variously described as the first Roman king to accede without election by the Senate, having gained the throne by popular and royal support; and as the first to be elected by the Senate alone, with support of the reigning queen but without recourse to a popular vote.

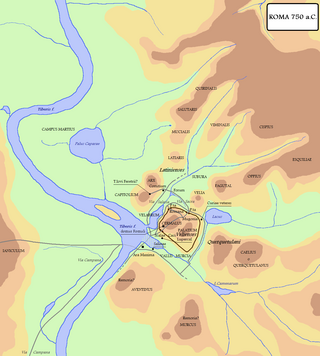

In Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus are twin brothers whose story tells of the events that led to the founding of the city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus, following his fratricide of Remus. The image of a she-wolf suckling the twins in their infancy has been a symbol of the city of Rome and the ancient Romans since at least the 3rd century BC. Although the tale takes place before the founding of Rome around 750 BC, the earliest known written account of the myth is from the late 3rd century BC. Possible historical bases for the story, and interpretations of its local variants, are subjects of ongoing debate.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was atticistic – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

In Roman legend, Tarpeia, daughter of the Roman commander Spurius Tarpeius, was a Vestal Virgin who betrayed the city of Rome to the Sabines at the time of their women's abduction for what she thought would be a reward of jewelry. She was instead crushed to death by Sabine shields and her body cast from the southern cliff of Rome's Capitoline Hill, thereafter called after her the Tarpeian Rock.

The Pyrrhic War was largely fought between the Roman Republic and Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus, who had been asked by the people of the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italy to help them in their war against the Romans.

The Battle of Beneventum was the last battle of the Pyrrhic War. It was fought near Beneventum, in southern Italy, between the forces of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus in Greece, and the Romans, led by consul Manius Curius Dentatus. The result was a Roman victory and Pyrrhus was forced to return to Tarentum, and later to Epirus.

Sextus Tarquinius was one of the sons of the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. In the original account of the Tarquin dynasty presented by Fabius Pictor, he is the second son, between Titus and Arruns. However, according to Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, he was either the third or first son, respectively. According to Roman tradition, his rape of Lucretia was the precipitating event in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic.

Secessio plebis was an informal exercise of power by Rome's plebeian citizens between the 5th century BC and 3rd century BC., similar in concept to the general strike. During the secessio plebis, the plebs would abandon the city en masse in a protest emigration and leave the patrician order to themselves. Therefore, a secessio meant that all shops and workshops would shut down and commercial transactions would largely cease. This was an effective strategy in the Conflict of the Orders due to strength in numbers; plebeian citizens made up the vast majority of Rome's populace and produced most of its food and resources, while a patrician citizen was a member of the minority upper class, the equivalent of the landed gentry of later times. Authors report different numbers for how many secessions there were. M. Cary and H. H. Scullard state there were five between 494 BC and 287 BC.

Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis or Inregillensis was the legendary founder of the Roman gens Claudia, and consul in 495 BC. He was the leading figure of the aristocratic party in the early Roman Republic.

The structural history of the Roman military concerns the major transformations in the organization and constitution of ancient Rome's armed forces, "the most effective and long-lived military institution known to history." At the highest level of structure, the forces were split into the Roman army and the Roman navy, although these two branches were less distinct than in many modern national defense forces. Within the top levels of both army and navy, structural changes occurred as a result of both positive military reform and organic structural evolution. These changes can be divided into four distinct phases.

Romulus was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of these traditions incorporate elements of folklore, and it is not clear to what extent a historical figure underlies the mythical Romulus, the events and institutions ascribed to him were central to the myths surrounding Rome's origins and cultural traditions.

Monte Cavo, or less often, "Monte Albano," is the second highest mountain of the complex of the Alban Hills, near Rome, Italy. An old volcano extinguished around 10,000 years ago, it lies about 20 km (12 mi) from the sea, in the territory of the comune of Rocca di Papa. It is the dominant peak of the Alban Hills. The current name comes from Cabum, an Italic settlement existing on this mountain.

Alba Longa was an ancient Latin city in Central Italy in the vicinity of Lake Albano in the Alban Hills. The ancient Romans believed it to be the founder and head of the Latin League, before it was destroyed by the Roman Kingdom around the middle of the 7th century BC and its inhabitants were forced to settle in Rome. In legend, Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome, had come from the royal dynasty of Alba Longa, which in Virgil's Aeneid had been the bloodline of Aeneas, a son of Venus.

The gens Verginia or Virginia was a prominent family at ancient Rome, which from an early period was divided into patrician and plebeian branches. The gens was of great antiquity. It frequently filled the highest honors of the state during the early years of the Republic. The first of the family who obtained the consulship was Opiter Verginius Tricostus in 502 BC, the seventh year of the Republic. The plebeian members of the family were also numbered amongst the early tribunes of the people.

The Roman–Sabine wars were a series of wars during the early expansion of ancient Rome in central Italy against their northern neighbours, the Sabines. It is commonly accepted that the events pre-dating the Roman Republic in 509 BC are semi-legendary in nature.

The Servian constitution was one of the earliest forms of military and political organization used during The Roman Republic. Most of the reforms extended voting rights to certain groups, in particular to Rome's citizen-commoners who were minor landholders or otherwise landless citizens hitherto disqualified from voting by ancestry, status or ethnicity, as distinguished from the hereditary patricians. The reforms thus redefined the fiscal and military obligations of all Roman citizens. The constitution introduced two elements into the Roman system of government: a census of every male citizen, in order to establish his wealth, tax liabilities, military obligation, and the weight of his vote; and the comitia centuriata, an assembly with electoral, legislative and judicial powers. Both institutions were foundational for Roman republicanism.

In Roman mythology, the Battle of the Lacus Curtius was the final battle in the war between the Roman Kingdom and the Sabines following Rome's mass abduction of Sabine women to take as brides. It took place during the reign of Romulus, near the Lacus Curtius, future site of the Roman Forum.

Servius Sulpicius Camerinus Cornutus was a Roman politician in the 5th century BC, consul in 461 BC and decemvir in 451 BC.

Spurius Oppius Cornicen was a Roman politician and member of the Second Decemvirate in 450 and 449 BC.

In Ancient Rome, there were four primary kinds of taxation: a cattle tax, a land tax, customs, and a tax on the profits of any profession. These taxes were typically collected by local aristocrats. The Roman state would set a fixed amount of money each region needed to provide in taxes, and the local officials would decide who paid the taxes and how much they paid. Once collected the taxes would be used to fund the military, create public works, establish trade networks, stimulate the economy, and to fund the cursus publicum.

References

- Appian; White, Horace (1913). "The Civil Wars". Lacus Curtis. Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Bagnall, B.; Frier, B. (1994). The Demography of Roman Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46123-5.

- Cassius Dio; Cary, E (1917). "Roman History". Lacus Curtis. Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus; Cary, E (1939). "The Roman Antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus". Lacus Curtis. Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Ligt, L; Northwood, S (2008), People, Land, and Politics Demographic Developments and the Transformation of Roman Italy, 300 BC-AD 14, Brill, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004171183.i-656, ISBN 9789047424499 , retrieved 17 September 2017

- Livy, T (1857), History of Rome by Titus Livius, the First Eight Books, translated by D. Spillian, London: Henry G. Bohn, John Child & Sons.

- Mersing, K. M (2007), "The War-tax (Tributum) of the Roman Republic: A Reconsideration", Classica et Mediaevalia, 58, Museum Tusculanum: 215–235, ISSN 0106-5815

- Nicolet, C. (1980) [1930], "Tributum in the Middle Republic", The World of the Citizen in Republican Rome , translated by P.S. Falla, London: Batsford Academic and Educational, ISBN 0713403683

- Rathbone, D (2001), "The Census Qualifications of the assidui and the prima classis", De Agricultura. In Memoriam Pieter Willem de Neeve, 58, Amsterdam: 121–152

- Rosenstein, N. (2016), "Tributum in the Middle Republic", Circum Mare: Themes in Ancient Warfare, vol. 388, Brill, pp. 80–97, doi:10.1163/9789004284852_006, ISBN 9789004284852