Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in which thin needles are inserted into the body. Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientific knowledge, and it has been characterized as quackery.

Alternative medicine is any practice that aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine despite lacking biological plausibility, testability, repeatability or evidence of effectiveness. Unlike modern medicine, which employs the scientific method to test plausible therapies by way of responsible and ethical clinical trials, producing repeatable evidence of either effect or of no effect, alternative therapies reside outside of mainstream medicine and do not originate from using the scientific method, but instead rely on testimonials, anecdotes, religion, tradition, superstition, belief in supernatural "energies", pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, or other unscientific sources. Frequently used terms for relevant practices are New Age medicine, pseudo-medicine, unorthodox medicine, holistic medicine, fringe medicine, and unconventional medicine, with little distinction from quackery.

Chiropractic is a form of alternative medicine concerned with the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of mechanical disorders of the musculoskeletal system, especially of the spine. It has esoteric origins and is based on several pseudoscientific ideas.

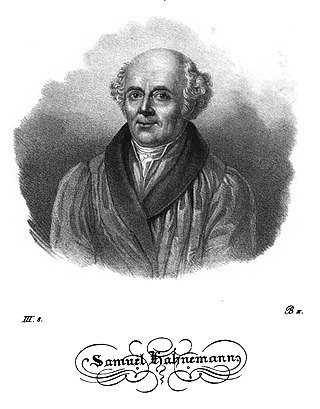

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a disease in healthy people can cure similar symptoms in sick people; this doctrine is called similia similibus curentur, or "like cures like". Homeopathic preparations are termed remedies and are made using homeopathic dilution. In this process, the selected substance is repeatedly diluted until the final product is chemically indistinguishable from the diluent. Often not even a single molecule of the original substance can be expected to remain in the product. Between each dilution homeopaths may hit and/or shake the product, claiming this makes the diluent "remember" the original substance after its removal. Practitioners claim that such preparations, upon oral intake, can treat or cure disease.

Naturopathy, or naturopathic medicine, is a form of alternative medicine. A wide array of practices branded as "natural", "non-invasive", or promoting "self-healing" are employed by its practitioners, who are known as naturopaths. Difficult to generalize, these treatments range from the pseudoscientific and thoroughly discredited, like homeopathy, to the widely accepted, like certain forms of psychotherapy. The ideology and methods of naturopathy are based on vitalism and folk medicine rather than evidence-based medicine, although practitioners may use techniques supported by evidence. The ethics of naturopathy have been called into question by medical professionals and its practice has been characterized as quackery.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) is a United States government agency which explores complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). It was initially created in 1991 as the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), and renamed the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) before receiving its current name in 2014. NCCIH is one of the 27 institutes and centers that make up the National Institutes of Health (NIH) within the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Simon Lehna Singh, is a British popular science author, theoretical and particle physicist. His written works include Fermat's Last Theorem, The Code Book, Big Bang, Trick or Treatment? Alternative Medicine on Trial and The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets. In 2012 Singh founded the Good Thinking Society, through which he created the website "Parallel" to help students learn mathematics.

Craniosacral therapy (CST) or cranial osteopathy is a form of alternative medicine that uses gentle touch to feel non-existent rhythmic movements of the skull's bones and supposedly adjust the immovable joints of the skull to achieve a therapeutic result. CST is a pseudoscience and its practice has been characterized as quackery. It is based on fundamental misconceptions about the anatomy and physiology of the human skull and is promoted as a cure-all for a variety of health conditions.

Anthroposophic medicine is a form of alternative medicine based on pseudoscientific and occult notions. Devised in the 1920s by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) in conjunction with Ita Wegman (1876–1943), anthroposophical medicine draws on Steiner's spiritual philosophy, which he called anthroposophy. Practitioners employ a variety of treatment techniques based upon anthroposophic precepts, including massage, exercise, counselling, and administration of substances.

Edzard Ernst is a retired British-German academic physician and researcher specializing in the study of complementary and alternative medicine. He was Professor of Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter, the world's first such academic position in complementary and alternative medicine.

Alternative cancer treatment describes any cancer treatment or practice that is not part of the conventional standard of cancer care. These include special diets and exercises, chemicals, herbs, devices, and manual procedures. Most alternative cancer treatments do not have high-quality evidence supporting their use and many have been described as fundamentally pseudoscientific. Concerns have been raised about the safety of some purported treatments and some have been found unsafe in clinical trials. Despite this, many untested and disproven treatments are used around the world.

Alternative veterinary medicine is the use of alternative medicine in the treatment of animals. Types alternative therapies used for veterinary treatments may include, but are not limited to, acupuncture, herbal medicine, homeopathy, ethnomedicine and chiropractic. The term includes many treatments that do not have enough evidence to support them being a standard method within many veterinary practices.

Osteomyology is a multi-disciplined form of alternative medicine found almost exclusively in the United Kingdom and is loosely based on aggregated ideas from other manipulation therapies, principally chiropractic and osteopathy. It is a results-based physical therapy tailored specifically to the needs of the individual patient. Osteomyologists have been trained in osteopathy and chiropractic, but do not require to be regulated by the General Osteopathic Council (GOsC) or the General Chiropractic Council (GCC).

The Prince's Foundation for Integrated Health (FIH) was a charity run by King Charles III founded in 1993. The foundation promoted complementary and alternative medicine, preferring to use the term "integrated health", and lobbied for its inclusion in the National Health Service. The charity closed in 2010 after allegations of fraud and money laundering led to the arrest of a former official.

George Lewith was a professor at the University of Southampton researching alternative medicine and a practitioner of complementary medicine. He was a prominent and sometimes controversial advocate of complementary medicine in the UK.

Because of the uncertain nature of various alternative therapies and the wide variety of claims different practitioners make, alternative medicine has been a source of vigorous debate, even over the definition of "alternative medicine". Dietary supplements, their ingredients, safety, and claims, are a continual source of controversy. In some cases, political issues, mainstream medicine and alternative medicine all collide, such as in cases where synthetic drugs are legal but the herbal sources of the same active chemical are banned.

The Friends of Science In Medicine (FSM) is an Australian association which supports evidence-based medicine and strongly opposes the promotion and practice of unsubstantiated therapies that lack a scientifically plausible rationale. They accomplish this by publicly raising their concerns either through direct correspondence or through media outlets. FSM was established in December 2011 by Loretta Marron, John Dwyer, Alastair MacLennan, Rob Morrison and Marcello Costa, a group of Australian biomedical scientists and clinical academics.

Klaus Linde is a German physician and alternative medicine researcher. He works at the Centre for Complementary Medicine Research at the Technical University of Munich in Germany.

Alternative medicine describes any practice which aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine, but which lacks biological plausibility and is untested or untestable. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), integrated medicine or integrative medicine (IM), and holistic medicine are among many rebrandings of the same phenomenon.

The infinitesimally low concentration of homeopathic preparations, which often lack even a single molecule of the diluted substance, has been the basis of questions about the effects of the preparations since the 19th century. Modern advocates of homeopathy have proposed a concept of "water memory", according to which water "remembers" the substances mixed in it, and transmits the effect of those substances when consumed. This concept is inconsistent with the current understanding of matter, and water memory has never been demonstrated to exist, in terms of any detectable effect, biological or otherwise.