The Cyrillic script, Slavonic script or simply Slavic script is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia, North Asia, and East Asia, and used by many other minority languages.

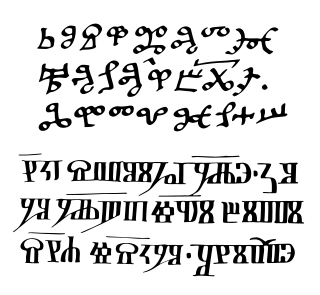

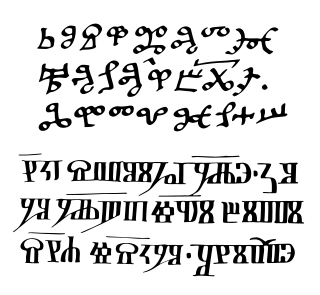

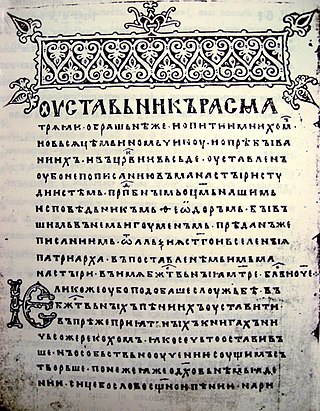

The Glagolitic script is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed that it was created in the 9th century for the purpose of translating liturgical texts into Old Church Slavonic by Saint Cyril, a monk from Thessalonica. He and his brother Saint Methodius were sent by the Byzantine Emperor Michael III in 863 to Great Moravia to spread Christianity there. After the deaths of Cyril and Methodius, their disciples were expelled and they moved to the First Bulgarian Empire instead. The Cyrillic alphabet, which developed gradually in the Preslav Literary School by Greek alphabet scribes who incorporated some Glagolitic letters, gradually replaced Glagolitic in that region. Glagolitic remained in use alongside Latin in the Kingdom of Croatia and alongside Cyrillic until the 14th century in the Second Bulgarian Empire and the Serbian Empire, and later mainly for cryptographic purposes.

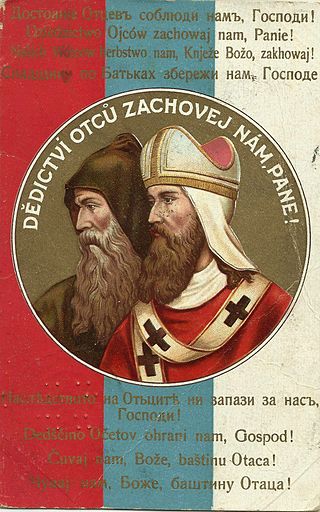

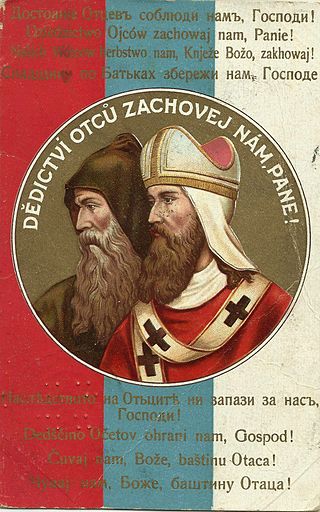

Cyril and Methodius (815–885) were brothers, Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic is the first Slavic literary language.

Great Moravia, or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to emerge in the area of Central Europe, possibly including territories which are today part of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Austria, Germany, Poland, Romania, Croatia, Serbia, Ukraine and Slovenia. The formations preceding it in these territories were the Samo's tribal union and the Pannonian Avar state.

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is a language that is cultivated and used primarily for religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

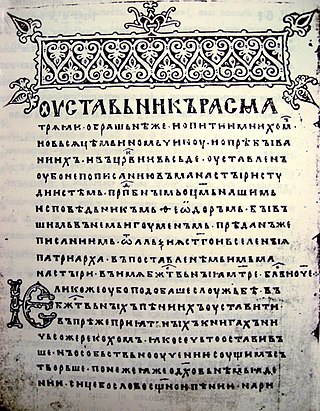

Church Slavonic, also known as Church Slavic, New Church Slavonic, New Church Slavic or just Slavonic, is the conservative Slavic liturgical language used by the Eastern Orthodox Church in Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Serbia, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia. The language appears also in the services of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese, and occasionally in the services of the Orthodox Church in America.

Naum (Bulgarian and Macedonian: Свети Наум, Sveti Naum, also known as Naum of Ohrid or Naum of Preslav, was a medieval Bulgarian writer and missionary among the Slavs, considered one of the Seven Apostles of the First Bulgarian Empire. He was among the disciples of Cyril and Methodius and is associated with the creation of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic script. Naum was among the founders of the Pliska Literary School. Afterwards Naum worked at the Ohrid Literary School. He was among the first saints declared by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church after its foundation in the 9th century. The mission of Naum played significant role by transformation of the local Early Slavs into Bulgarians.

Constantine of Preslav was a medieval Bulgarian scholar, writer and translator, one of the most important men of letters working at the Preslav Literary School at the end of the 9th and the beginning of the 10th century. Biographical evidence about his life is scarce but he is believed to have been a disciple of Saint Methodius. After the saint's death in 885, Constantine was jailed by the Germanic clergy in Great Moravia and sold as slave in Venice. He escaped to Constantinople, moving to Bulgaria around 886 and working at the Preslav Literary School.

Tyniec is a historic village in Poland on the Vistula river, since 1973 a part of the city of Kraków. Tyniec is notable for its Benedictine abbey founded by King Casimir the Restorer in 1044.

Ihor Ševčenko was a Polish-born philologist and historian of Ukrainian origin. He was a Byzantinist and paleo-Slavic professor of classical philology at Harvard University. He died 26 December 2009 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Euchologium Sinaiticum is a 109-folio Old Church Slavonic euchologion in Glagolitic script. It contains parts of the liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, and is dated to the 11th century. It is named after Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai, where it was found in the 19th century.

As the 9th-century missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius undertook their mission to evangelize to the Slavs of Great Moravia, two writing systems were developed: Glagolitic and Cyrillic. Both scripts were based on the Greek alphabet and share commonalities, but the exact nature of relationship between the Glagolitic alphabet and the Early Cyrillic alphabet, their order of development, and influence on each other has been a matter of great study, controversy, and dispute in Slavic studies.

In the 9th century, Christianity was spreading throughout Europe, being promoted especially in the Carolingian Empire, its eastern neighbours, Scandinavia, and northern Spain. In 800, Charlemagne was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor, which continued the Photian schism.

Christianity in the Middle Ages covers the history of Christianity from the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end of the period is variously defined. Depending on the context, events such as the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Christopher Columbus's first voyage to the Americas in 1492, or the Protestant Reformation in 1517 are sometimes used.

The Christianization of Moravia refers to the spread of the Christian religion in the lands of medieval Moravia.

The history of Christianity in the Czech lands began in the 9th century. Moravia was the first among the three historical regions of what now forms the Czech Republic whose ruling classes officially adopted Christianity, between the 830s and the 860s. In 845 Bohemian chieftains or duces also converted to the new faith, but it was just a short-lived political gesture. The real beginning of efforts to promote Christianity in Bohemian territory has to be placed in the period after 885. Moravia was the earliest center of the Old Church Slavonic liturgy after the arrival of Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius in 863, but their opponents, mainly priests of German origin, achieved the banishment of their disciplines in the 880s. Bohemia became the center of Christianization following the fall of Moravia in the early 10th century. Changes in burials and the erection of churches throughout the Czech lands demonstrate the spread of the new faith in the 10th century.

The Archbishopric of Moravia was an ecclesiastical province, established by the Holy See to promote Christian missions among the Slavic peoples. Its first archbishop, the Byzantine Methodius, persuaded Pope John VIII to sanction the use of Old Church Slavonic in liturgy. Methodius had been consecrated archbishop of Pannonia by Pope Adrian II at the request of Koceľ, the Slavic ruler of Pannonia in East Francia in 870.

The Slavs were Christianized in waves from the 7th to 12th century, though the process of replacing old Slavic religious practices began as early as the 6th century. Generally speaking, the monarchs of the South Slavs adopted Christianity in the 9th century, the East Slavs in the 10th, and the West Slavs between the 9th and 12th century. Saints Cyril and Methodius are attributed as "Apostles to the Slavs", having introduced the Byzantine-Slavic rite and Glagolitic alphabet, the oldest known Slavic alphabet and basis for the Early Cyrillic alphabet.

Cyrillo-Methodian studies is a branch of Slavic studies dealing with the life and works of Cyril and Methodius and their disciples.