In archaeology and anthropology, the term excarnation refers to the practice of removing the flesh and organs of the dead before burial. Excarnation may be achieved through natural means, such as leaving a dead body exposed to the elements or for animals to scavenge; or by butchering the corpse by hand. Following excarnation, some societies retrieved the excarnated bones for burial. Excarnation has been practiced throughout the world for hundreds of thousands of years. The earliest archaeological evidence of excarnation is from the Awash River Valley in Ethiopia, 160,000 years ago. Examples of excarnation include "sky burials" in parts of Asia, the Zoroastrian "Tower of Silence", and Native American "tree burials". Excarnation is practiced for a variety of spiritual and practical reasons, including the Tibetian spiritual belief that excarnation is the most generous form of burial and the Comanche practical concern that in the winter the ground is too hard for an underground burial. Excarnation sites are identifiable in the archaeological record by a concentration of smaller bones, which would be the bones that would be the easiest to fall off the body, and that would not be noticed by practitioners of excarnation.

Rangda is the demon queen of the Leyaks in Bali, according to traditional Balinese mythology. Terrifying to behold, the child-eating Rangda leads an army of evil witches against the leader of the forces of good — Barong. The battle between Barong and Rangda is featured in a Barong dance which represents the eternal battle between good and evil.

Barong is a panther-like creature and character in the Balinese mythology of Bali, Indonesia. He is the king of the spirits, leader of the hosts of good, and enemy of Rangda, the demon queen and mother of all spirit guarders in the mythological traditions of Bali. The battle between Barong and Rangda is featured in the Barong dance to represent the eternal battle between good and evil.

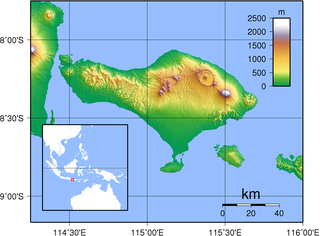

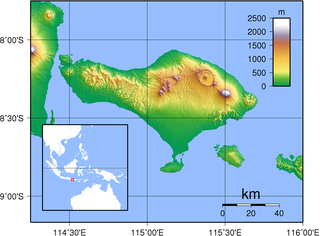

Subak is the water management (irrigation) system for the paddy fields on Bali island, Indonesia. It was developed in the 9th century. For the Balinese, irrigation is not simply providing water for the plant's roots, but water is used to construct a complex, pulsed artificial ecosystem that is at the same time autonomous and interdependent. The system consists of five terraced rice fields and water temples covering nearly 20,000 hectares. The temples are the main focus of this cooperative water management, known as subak.

Balinese dance is an ancient dance tradition that is part of the religious and artistic expression among the Balinese people of Bali island, Indonesia. Balinese dance is dynamic, angular, and intensely expressive. Balinese dancers express the stories of dance-drama through bodily gestures including gestures of fingers, hands, head, and eyes.

Pura Ulun Danu Batur is a Hindu Balinese temple located on the island of Bali, Indonesia. As one of the Pura Kahyangan Jagat, Pura Ulun Danu Batur is one of the most important temples in Bali which acted as the maintainer of harmony and stability of the entire island. Pura Ulun Danu Batur represents the direction of the North and is dedicated to the god Vishnu and the local goddess Dewi Danu, goddess of Lake Batur, the largest lake in Bali. Following the destruction of the original temple compound, the temple was relocated and rebuilt in 1926. The temple, along with 3 other sites in Bali, form the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province which was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2012.

A Pura is a Balinese Hindu temple and the place of worship for adherents of Balinese Hinduism in Indonesia. Puras are built following rules, style, guidance, and rituals found in Balinese architecture. Most puras are found on the island of Bali, where Hinduism is the predominant religion; however many puras exist in other parts of Indonesia where significant numbers of Balinese people reside. Mother Temple of Besakih is the most important, largest, and holiest temple in Bali. Many Puras have been built in Bali, leading it to be titled "the Island of a Thousand Puras".

Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali is a 1980 book written by anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Geertz argues that the pre-colonial Balinese state was not a "hydraulic bureaucracy" nor an oriental despotism, but rather, an organized spectacle. The noble rulers of the island were less interested in administering the lives of the Balinese than in dramatizing their rank and enhance political superiority through large public rituals and ceremonies. These cultural processes did not support the state, he argues, but were the state.

It is perhaps most clear in what was, after all, the master image of political life: kingship. The whole of the negara - court life, the traditions that organized it, the extractions that supported it, the privileges that accompanied it - was essentially directed toward defining what power was; and what power was what kings were. Particular kings came and went, 'poor passing facts' anonymized in titles, immobilized in ritual, and annihilated in bonfires. But what they represented, the model-and-copy conception of order, remained unaltered, at least over the period we know much about. The driving aim of higher politics was to construct a state by constructing a king. The more consummate the king, the more exemplary the centre. The more exemplary the centre, the more actual the realm.

Omed-omedan, also known as "The Kissing Ritual", is a ceremony that is held by the young people of Banjar Kaja Sesetan, Denpasar, Bali. Omed-omedan is held on the day of ngembak geni to celebrate the Saka new year. The name is derived from the Balinese language and means pull-pull.

The Kingdomship of Bali was a series of Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms that once ruled some parts of the volcanic island of Bali, in Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia. With a history of native Balinese kingship spanning from the early 10th to early 20th centuries, Balinese kingdoms demonstrated sophisticated Balinese court culture where native elements of spirit and ancestral reverence combined with Hindu influences—adopted from India through ancient Java intermediary—flourished, enriched and shaped Balinese culture.

The Ubud Palace, officially Puri Saren Agung, is a historical building complex situated in Ubud, Gianyar Regency of Bali, Indonesia.

Pura Taman Ayun is a compound of Balinese temple and garden located in Mengwi district (kecamatan) in Badung Regency, Bali, Indonesia. Its water features are an integral part of the local subak system.

Balinese theatre and dramas include Janger dance, pendet dance performances, and masked performances of Topèng. Performances are also part of funeral rituals involving a procession, war dance, and other rituals before the cremation of the patulangan. Balinese use the word sesolahan for both theatre and dance.

Pura Griya Sakti is a Balinese Hindu temple located in the village of Manuaba, Kenderan administrative village, Tegalalang subdistrict, Gianyar Regency, Bali. The district is known for its woodcarving and its terraced rice field. The small village of Manuaba is about 4 km north of Kenderan or about 2.5 km southwest of the town of Tampaksiring with its famed Gunung Kawi temple. Pura Griya Sakti is the main temple of a powerful Brahman caste in the area.

Pura Kehen is a Balinese Hindu temple located in Cempaga, Bangli Regency, Bali. The temple is set on the foot of a wooded hill, about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of the town center. Established at least in the 13th-century, Pura Kehen was the royal temple of the Bangli Kingdom, now the Regency of Bangli.

Pura Taman Saraswati, officially Pura Taman Kemuda Saraswati, also known as the Ubud Water Palace, is a Balinese Hindu temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. The pura is dedicated to the goddess Sarasvati. Pura Taman Saraswati is notable for its lotus pond.

Pura Beji Sangsit is a Balinese temple or pura located in Sangsit, Buleleng, on the island of Bali, Indonesia. The village of Sangsit is located around 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) east of Singaraja. Pura Beji is dedicated to the rice goddess Dewi Sri, and is revered especially by the farmers around the area. Pura Beji is an example of a stereotypical northern Balinese architecture with its relatively heavier decorations than it is southern Balinese counterpart, and its typical foliage-like carvings.

Pura Maospahit is a Balinese Hindu temple or pura located in Denpasar, Bali. The pura is known for its bare red brick architecture, reminiscent of the architecture of the 13th-century Majapahit Kingdom, hence the name. Pura Maospahit is the only pura in Bali which was built using a concept known as Panca Mandala where the most sacred area is situated at the center instead of at the direction of the mountain.

Pura Dasar Buana is a Balinese Hindu temple or pura located in Gelgel, Bali, about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from Semarapura. Pura Dasar Buana is one of the Pura Dang Kahyangan Jagat, a temple which was built to honor a holy teacher of Hindu teaching. Pura Dasar Buana honored Mpu Ghana, a Brahmin who arrived to Bali from Javanese Majapahit to teach Hinduism in the island.