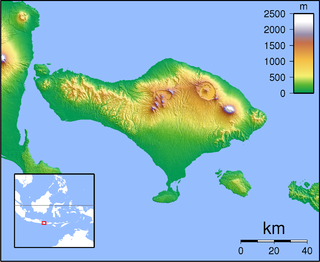

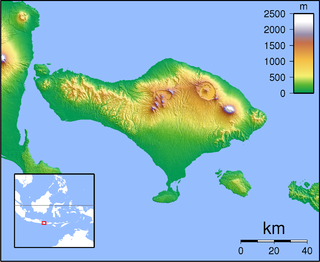

Klungkung Regency is the smallest regency (kabupaten) in the island province of Bali, Indonesia. It has an area of 315 km2 and had a population at the 2010 Census of 170,543 which increased to 206,925 at the Census of 2020; the official estimate as at mid 2022 was 214,012. The administrative centre for the regency is in the town of Semarapura.

The Klungkung Palace, officially Puri Agung Semarapura, is a historical building complex situated in Semarapura, the capital of the Klungkung Regency (kabupaten) on Bali, Indonesia.

Dewa Agung or Deva Agung was the title of the kings of Klungkung, the foremost in rank among the nine kingdoms of Bali, Indonesia. It was also borne by other high-ranking members of the dynasty. The term Dewa means "god" and was also a general title for members of the Ksatria caste. Agung translates as "high" or "great". Literally, the title therefore means Great God.

The History of Bali covers a period from the Paleolithic to the present, and is characterized by migrations of people and cultures from other parts of Asia. In the 16th century, the history of Bali started to be marked by Western influence with the arrival of Europeans, to become, after a long and difficult colonial period under the Dutch, an example of the preservation of traditional cultures and a key tourist destination.

Babad Dalem is a historical account from Bali, Indonesia, which exists in a large number of versions of varying length. The title may be translated as "Chronicle of Kings", although the Balinese babad genre does not quite accord to Western-style chronicles. There are dated manuscripts from the early 19th century onwards, and the original version was very likely written in the course of the 18th century. The author was probably a Brahmin tied to the Klungkung Palace, the most prestigious of the nine pre-colonial royal seats of Bali.

Dalem was a title for the kings of Bali who resided in Samprangan and Gelgel and were descended from the founder-raja Sri Aji Kresna Kepakisan. These kings ruled the island, or at least substantial parts thereof, from maybe the 14th century to the second half of the 17th century. The title literally means "inside", and alludes to his ritual-symbolic role inside the palace (puri). The title is first found in a Dutch report from 1619, which says that the Radia Dalam was the paramount ruler of 33 lesser Balinese lords. The title is used in the chronicle Babad Dalem from the 18th century, which recounts the history of the kings of Bali up the end of the 17th century. After the fall of the Gelgel kingdom in 1686, a daughter kingdom was established in nearby Klungkung. However, the rulers of the Klungkung Palace were usually known by another title, Dewa Agung. In the literature, Dewa Agung is sometimes, although anachronistically, used also for the pre-1686 kings of Bali.

Dalem Baturenggong, also called Waturenggong or Enggong, was a King (Dalem) of Bali who is believed to have reigned in the mid 16th century. He is in particular associated with the golden age of the Balinese kingdom of Gelgel, with political expansion and cultural and religious renovation. In Balinese historiography he represented an epic vision of kingship that served as a model for later rulers on the island.

Sri Aji Kresna Kepakisan was a king of Bali who governed the island under the suzerainty of the Javanese Majapahit Empire. He is supposed to have ruled in the mid-14th century, and to be the ancestor of the later kings of Bali. His historicity is, however, not clearly documented.

Dalem Samprangan was a king of Bali who governed under the suzerainty of the Javanese Majapahit Empire, and belonged to a dynasty of immigrants from Java. The exact dating of his reign is unclear; the sources point at either the second half of the 14th century or the early 16th century.

Dalem Ketut was a king (Dalem) of Bali who ruled at an uncertain time during the age of the Javanese Majapahit Empire. While first a vassal ruler under the Majapahit kings, he later emerged as the king of a separate island realm. He was also known under the names Sri Smara Kepakisan or Tegal Besung. Dewa Tegal Besung is the earliest deified ruler who is honoured at the Pura Padharman Dalem Gelgel, the most important shrine at the central Balinese temple Pura Besakih.

Dalem Bekung, also known as Pamayun, was a king of Bali who is traditionally dated in the second half of the 16th century. He belonged to a dynasty of kings who were descended from Majapahit on Java, and reigned from their palace (puri) in Gelgel.

Dalem Segening was a king of Bali who reigned in the first half of the 17th century, his exact dating being still uncertain. He belonged to a dynasty which originated from Majapahit on Java, and ruled from the palace (puri) of Gelgel.

Dalem Di Made was a king of Bali who may have reigned in the period 1623–1642. He belonged to a dynasty that claimed descent from the Majapahit Empire of Java, and kept residence in Gelgel, close to Bali's south coast.

Anglurah Agung, also known as Gusti Agung Di Made or Gusti Agung Maruti, was a king of Gelgel, the paramount kingdom on Bali, who ruled at a time when the political unity of the island began to break down. This process led to the permanent division of Bali into several minor kingdoms by the late 17th century.

Dewa Pacekan was a prince on the Island of Bali, who possibly ruled the island kingdom for a short time, in 1642–1650. He belonged to a dynasty stemming from the Majapahit Empire of Java, which had its palace (puri) in Gelgel, near Bali's south coast. According to Balinese historiography he was the second son of king Dalem Di Made, who may have died in 1642. In Dutch sources from the 1630s, he appears to be mentioned as 'Patiekan' or 'Paadjakan', son of the current ruler. In the religious text Rajapurana Besakih, he is listed as the last deified ancestor of the Gelgel dynasty. He may therefore have succeeded Dalem Di Made, although later Balinese historical texts do not actually mention him as ruler in his own right. One text mentions that he directed his troops against the army of the Javanese Muslim Mataram kingdom in 1646. This confrontation is also described in Dutch and Javanese sources. His death is placed by Balinese texts in 1650. Dutch sources relate that the Dutch East Indies Company sent an embassy to Bali in 1651, but found on arrival that the unnamed king had recently died, and that chaotic internecine wars raged on the island.

Dewa Cawu was a prince on the Island of Bali, who possibly reigned as king for a short while in the 1650s. He belonged to a dynasty that claimed descent from the Hindu-Javanese Majapahit Empire, and kept its palace (puri) in Gelgel near Bali's south coast.

The Blambangan Kingdom was the last Javanese Hindu kingdom that flourished between the 13th and 18th centuries, based in the eastern corner of Java. The capital was at Banyuwangi. It had a long history of its own, developing contemporaneously with the largest Hindu kingdom in Java, Majapahit (1293–1527). At the time of the collapse of Majapahit in the late fifteenth century, Blambangan stood on its own as the one solitary Hindu state left in Java, controlling the larger part of Java’s Oosthoek.

The Kingdomship of Bali was a series of Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms that once ruled some parts of the volcanic island of Bali, in Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia. With a history of native Balinese kingship spanning from the early 10th to early 20th centuries, Balinese kingdoms demonstrated sophisticated Balinese court culture where native elements of spirit and ancestral reverence combined with Hindu influences—adopted from India through ancient Java intermediary—flourished, enriched and shaped Balinese culture.

Pura Dasar Buana is a Balinese Hindu temple or pura located in Gelgel, Bali, about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from Semarapura. Pura Dasar Buana is one of the Pura Dang Kahyangan Jagat, a temple which was built to honor a holy teacher of Hindu teaching. Pura Dasar Buana honored Mpu Ghana, a Brahmin who arrived to Bali from Javanese Majapahit to teach Hinduism in the island.