Related Research Articles

Sumter County is a county located in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 105,556. Its county seat is Sumter.

Dalzell is a census-designated place (CDP) in Sumter County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 3,175 at the 2020 census. It is included in the Sumter, South Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Sumter is a city in and the county seat of Sumter County, South Carolina, United States. The city makes up the Sumter, SC Metropolitan Statistical Area. Sumter County, along with Clarendon and Lee counties, form the core of Sumter–Lee–Clarendon tri-county area of South Carolina that includes three counties straddling the border of the Sandhills, Pee Dee, and Lowcountry regions. The population was 43,463 at the 2020 census, making it the 9th-most populous city in the state.

The Székelys, also referred to as Szeklers, are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. In addition to their native villages in Suceava County in Bukovina, a significant population descending from the Székelys of Bukovina currently lives in Tolna and Baranya counties in Hungary and certain districts of Vojvodina, Serbia.

The Lumbee are a Native American people primarily centered in Robeson, Hoke, Cumberland, and Scotland counties in North Carolina.

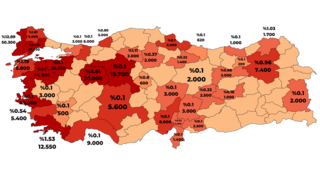

Turkish people or Turks are the largest Turkic people who speak various dialects of the Turkish language and form a majority in Turkey and Northern Cyprus. In addition, centuries-old ethnic Turkish communities still live across other former territories of the Ottoman Empire. Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a Turk as anyone who is a citizen of Turkey. While the legal use of the term Turkish as it pertains to a citizen of Turkey is different from the term's ethnic definition, the majority of the Turkish population are of Turkish ethnicity. The vast majority of Turks are Muslims and follow the Sunni faith.

Gurbeti are a sub-group of the Romani people living in Cyprus and North Cyprus, Turkey, Crimea, Albania, Serbia and the former Yugoslavia whose members are Eastern Orthodox and predominantly Muslim Roma. The Gurbeti make up approximately two thirds of the population of Roma in Mačva, many of whom work in agriculture. In Kosovo, other Romani groups viewed the Gurbeti negatively.

Tatars in Bulgaria are Crimean Tatar, but also Nogai Tatar minorities in Bulgaria.

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly applied to mean specifically Turkish rather than merely Turkic, meaning that it refers more frequently to the Ottoman Empire's policies or the Turkish nationalist policies of the Republic of Turkey toward ethnic minorities in Turkey. As the Turkic states developed and grew, there were many instances of this cultural shift.

The Turkish diaspora refers to ethnic Turkish people who have migrated from, or are the descendants of migrants from, the Republic of Turkey, Northern Cyprus or other modern nation-states that were once part of the former Ottoman Empire. Therefore, the Turkish diaspora is not only formed by people with roots from mainland Anatolia and Eastern Thrace ; rather, it is also formed of Turkish communities which have also left traditional areas of Turkish settlements in the Balkans, the island of Cyprus, the region of Meskhetia in Georgia, and the Arab world.

Turkish Americans or American Turks are Americans of ethnic Turkish origin. The term "Turkish Americans" can therefore refer to ethnic Turkish immigrants to the United States, as well as their American-born descendants, who originate either from the Ottoman Empire or from post-Ottoman modern nation-states. The majority trace their roots to the Republic of Turkey, however, there are also significant ethnic Turkish communities in the US which descend from the island of Cyprus, the Balkans, North Africa, the Levant and other areas of the former Ottoman Empire. Furthermore, in recent years there has been a significant number of ethnic Turkish people coming to the US from the modern Turkish diaspora, especially from the Turkish Meskhetian diaspora in Eastern Europe and "Euro-Turks" from Central and Western Europe.

John Glen Browder is a former member of the United States House of Representatives from Alabama's 3rd congressional district. Browder was born in Sumter, South Carolina and graduated in 1961 from Edmunds High School in Sumter. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in history at Presbyterian College in Clinton, South Carolina, in 1965. He went on to obtain a Master of Arts and a Ph.D. in political science from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1971.

Its members are referred to as Turkish Gypsy, Türk Çingeneler, Turski Tsigani, Turkogifti (τουρκο-γύφτοι), Țigani turci, Török Cigányok, Turci Cigani. Through self-Turkification and assimilation in the Turkish culture over centuries, this Muslim Roma have adopted the Turkish language and lost Rumelian Romani language, in order to establish a Turkish identity to become more recognized by the host population and deny their Romani background to show their Turkishness. During a population census they declared themselves as Turks instead as Roma, however Turks consider them as fake-Turks, and Christian Romani do not consider them as part of the Romani society. They are cultural Muslims who adopted Sunni Islam of Hanafi madhab and religious male circumcision at the time of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate and Ottoman Empire.

The Romani people in Turkey or Turks of Romani background are Turkish citizens and the biggest subgroup of the Turkish Roma. They are Sunni Muslims mostly of Sufi orientation, who speak Turkish as their first language, in their own accent, and have adopted Turkish culture. Many have denied their Romani background over the centuries in order to establish a Turkish identity, to become more accepted by the host population. They identify themselves as Turks of Oghuz ancestry. More specifically, some have claimed to be members of the Yörüks, Amuca, Gajal or Tahtacı.

The Turkish communities in the former Ottoman Empire refers to ethnic Turks, who are the descendants of Ottoman-Turkish settlers from Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, living outside of the modern borders of the Republic of Turkey and in the independent states which were formerly part of the Ottoman Empire. Thus, they are not considered part of Turkey's modern diaspora, rather, due to living for centuries in their respective regions, they are now considered "natives" or "locals" as they have been living in these countries prior to the independence and establishment of the modern-nation states.

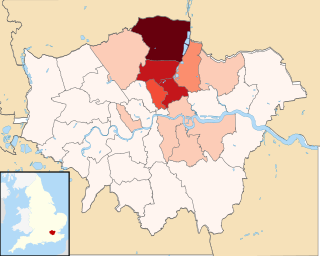

Turks in London or London Turks refers to Turkish people who live in London, the capital city of the United Kingdom. The Turkish community in the United Kingdom is not evenly distributed across the country. As a result, the concentration of the Turks is almost all in Greater London. The Turks have created Turkish neighbourhoods mostly in North and North-East London however there are also Turkish communities in South London and the City of Westminster.

William Ellison Jr., born April Ellison, was an American cotton gin maker and blacksmith in South Carolina, and former African-American slave who achieved considerable success as a slaveowner before the American Civil War. He eventually became a major planter and one of the wealthiest property owners in the state. According to the 1860 census, he owned up to 68 black slaves, making him the largest of the 171 black slaveholders in South Carolina. He held 63 slaves at his death and more than 900 acres (360 ha) of land. From 1830 to 1865 he and his sons were the only free blacks in Sumter County, South Carolina to own slaves. The county was largely devoted to cotton plantations, and the majority population were slaves.

Turco-Albanian is an ethnographic, religious, and derogatory term used by Greeks for Muslim Albanians from 1715 and thereafter. In a broader sense, the term included both Muslim Albanian and Turkish political and military elites of the Ottoman administration in the Balkans. The term is derived from an identification of Muslims with Ottomans and/or Turks, due to the Ottoman Empire's administrative millet system of classifying peoples according to religion, where the Muslim millet played the leading role. From the middle of the nineteenth century, the term Turk and from the late nineteenth century onwards, the derivative term Turco-Albanian has been used as a pejorative term, phrase and or expression for Muslim Albanian individuals and communities. The term has also been noted to be unclear, ideologically and sentimentally charged, and an imperialist and racialist expression. Albanians have expressed derision and disassociation toward the terms Turk and its derivative form Turco-Albanian regarding the usage of those terms in reference to them. It has been reported that at the end of the 20th century some Christian Albanians still used the term "Turk" to refer to Muslim Albanians.

Albanians in Turkey are ethnic Albanian citizens and denizens of Turkey. They consist of Albanians who arrived during the Ottoman period, Kosovar/Macedonian and Tosk Cham Albanians fleeing from Serbian and Greek persecution after the beginning of the Balkan Wars, alongside some Albanians from Montenegro and Albania proper. A 2008 report from the Turkish National Security Council (MGK) estimated that approximately 1.3 million people of Albanian ancestry live in Turkey, and more than 500,000 recognizing their ancestry, language and culture. There are other estimates however that place the number of people in Turkey with Albanian ancestry and background upward to 5 or 6 million.

References

- Terri Ann Ognibene; Glen Browder (2018). South Carolina's Turkish People: A History and Ethnology. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781611178593.