Related Research Articles

A xebec, also spelled zebec, was a Mediterranean sailing ship that was used mostly for trading. Xebecs had a long overhanging bowsprit and aft-set mizzen mast. The term can also refer to a small, fast vessel of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, used almost exclusively in the Mediterranean Sea.

A block and tackle or only tackle is a system of two or more pulleys with a rope or cable threaded between them, usually used to lift heavy loads.

A sea shanty, chantey, or chanty is a genre of traditional folk song that was once commonly sung as a work song to accompany rhythmical labor aboard large merchant sailing vessels. They were found mostly on British and other European ships, and some had roots in lore and legend. The term shanty most accurately refers to a specific style of work song belonging to this historical repertoire. However, in recent, popular usage, the scope of its definition is sometimes expanded to admit a wider range of repertoire and characteristics, or to refer to a "maritime work song" in general.

The Battle of Oliwa, also known as the Battle of Oliva, or the Battle of Gdańsk Roadstead, was a naval battle that took place on 28 November 1627 slightly north of the port of Danzig off the coast of the village of Oliva, during the Polish–Swedish War. It was the largest naval engagement ever fought by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Navy, and resulted in the defeat of a Swedish squadron led by Niels Stiernsköld that was conducting a blockade of the harbour of Danzig. The Poles sailed out of the Danzig harbour and engaged the Swedish squadron, capturing the Swedish flagship and sinking another Swedish warship.

A longboat is a type of ship's boat that was in use from circa 1500 or before. Though the Royal Navy replaced longboats with launches from 1780, examples can be found in merchant ships after that date. The longboat was usually the largest boat carried. In the early period of use, a ship's longboat was often so large that it could not be carried on board, and was instead towed. For instance, a survey of 1618 of Royal Navy ship's boats listed a 52 ft 4 in longboat used by the First Rate Prince, a ship whose length of keel was 115 ft. This could lead to the longboat being lost in adverse weather. By the middle of the 17th century it became increasingly more common to carry the longboat on board, though not universally. In 1697 some British ships in chase of a French squadron cut adrift the longboats they were towing in an attempt to increase their speed and engage with the enemy.

A monkey's fist or monkey paw is a type of knot, so named because it looks somewhat like a small bunched fist/paw. It is tied at the end of a rope to serve as a weight, making it easier to throw, and also as an ornamental knot. This type of weighted rope can be used as a hand-to-hand weapon, called a slungshot by sailors. It was also used in the past as an anchor in rock climbing, by stuffing it into a crack. Nowadays it is still sometimes used in sandstone, e.g., the Elbe Sandstone Mountains in Germany.

A cutter is a sailing vessel which is distinguished from a sloop by having more than one foresails, and the main mast stepped slightly further back. Cutters are most commonly private yachts but the term may also be used for some rowing or power boats, for example, the United States Coast Guard Cutter.

This is a glossary of nautical terms; some remain current, while many date from the 17th to 19th centuries. See also Wiktionary's nautical terms, Category:Nautical terms, and Nautical metaphors in English. See the Further reading section for additional words and references.

A boatswain's call, pipe or bosun's whistle is a pipe or a non-diaphragm type whistle used on naval ships by a boatswain. It is pronounced, and sometimes spelled, "bosun's call".

A volley gun is a gun with multiple single-shot barrels that shoot projectiles in volley fire, either simultaneously or in succession. Although capable of unleashing intense firepower, volley guns differ from modern machine guns in that they lack autoloading and automatic fire mechanisms, and therefore their volume of fire is limited by the number of barrels bundled together.

A gun carriage is a frame and mount that supports the gun barrel of an artillery piece, allowing it to be manoeuvred and fired.

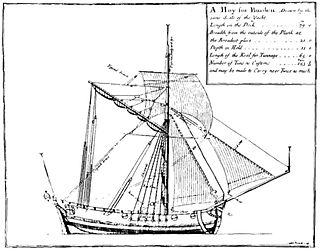

A hoy was a small sloop-rigged coasting ship or a heavy barge used for freight, usually with a burthen of about 60 tons (bm). The word derives from the Middle Dutch hoey. In 1495, one of the Paston Letters included the phrase, An hoye of Dorderycht, in such a way as to indicate that such contact was then no more than mildly unusual. The English term was first used on the Dutch Heude-ships that entered service with the Royal Navy.

Naval artillery in the Age of Sail encompasses the period of roughly 1571–1862: when large, sail-powered wooden naval warships dominated the high seas, mounting a bewildering variety of different types and sizes of cannon as their main armament. By modern standards, these cannon were extremely inefficient, difficult to load, and short ranged. These characteristics, along with the handling and seamanship of the ships that mounted them, defined the environment in which the naval tactics in the Age of Sail developed.

The junk rig, also known as the Chinese lugsail or sampan rig, is a type of sail rig in which rigid members, called battens, span the full width of the sail and extend the sail forward of the mast.

The first usage of cannon in Great Britain was possibly in 1327, when they were used in battle by the English against the Scots. Under the Tudors, the first forts featuring cannon batteries were built, while cannon were first used by the Tudor navy. Cannon were later used during the English Civil War for both siegework and extensively on the battlefield.

A Lyle gun was a line thrower powered by a short-barrelled cannon. It was invented by Captain David A. Lyle, US Army, a graduate of West Point and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and were used from the late 19th century to 1952, when they were replaced by rockets for throwing lines.

A gyn is an improvised three legged lifting device used on sailing ships. It provides more stability than a derrick or sheers, and requires no rigging for support. Without additional support, however, it can only be used for lifting things directly up and down. Gyns may also be used to support either end of a ropeway.

The Battle of 4 May was fought in open sea near Salvador, Bahia, on 4 May 1823, between the Brazilian Navy, under the command of a former admiral of the British Royal Navy, Thomas Cochrane, and the Portuguese Navy during the Brazilian War of Independence.

The Montagu whaler was the standard seaboat of the Royal Navy between 1910- 1970, it was a clinker built 27 by 6 feet open boat, which could be pulled by oars or powered by sail. It was double-ended; having a pointed stem and stern. The design of this naval whaler, was proposed by retired Rear Admiral The Honourable Victor Alexander Montagu in 1890 to replace a variety of smaller craft with one single, versatile craft.

References

- Don't Panic - Square Rig Seamanship the Easy Way, published by the Tall Ships Youth Trust, June 2001

- "Home > Operations and Support > Surface Fleet > Mine Countermeasure > Sandown Class > HMS Bangor > Photo Gallery". Royal Navy . Retrieved 2009-02-28.

‘Two, six, heave’: LOM(MW) Steve Baxter leads the Aintree Tug-O-War team in action

- ↑ "Happy Days: A Paper for Young and Old". 1915.

- ↑ Binney, George (1925). "With Seaplane and Sledge in the Arctic".

- ↑ Admiralty, Great Britain (1951). "Manual of Seamanship".

- ↑ Hartley, Peter Goodwin (1952). "Escape to Captivity".

- ↑ "Aeroplane and Commercial Aviation News". 1968.

- ↑ "A Visit to the United States and Canada in 1833; with the view of settling in America, etc". 1836.

- ↑ Neale, William Johnson (1840). "The Lost Ship".

- ↑ "Firefighting expressions". Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society . Retrieved 2009-02-28.

The use of ex-sailors certainly left its mark on the London brigade. Firemen are hands who work in watches denoted by bell signals. There are no ropes, only lines. At one time the working cap of London was the peakless fore and aft cap of the seaman. When firemen pull or lift they count 'two, six, heave', not one, two, three. This, I have discovered, dates back to the days of muzzle loading cannon on the wooden warships. When the gun was fired it came inboard, after reloading it was pulled out by a block and tackle on each side operated by numbers two and six of the gun's crew. Thus the number one gave the order 'two, six, heave'.