DomJoseph I, known as the Reformer, was King of Portugal from 31 July 1750 until his death in 1777. Among other activities, Joseph was devoted to hunting and the opera. His government was controlled by Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal.

DonaMaria I was Queen of Portugal from 24 February 1777 until her death in 1816. Known as Maria the Pious in Portugal and Maria the Mad in Brazil, she was the first undisputed queen regnant of Portugal and the first monarch of Brazil.

D. Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal and 1st Count of Oeiras, known as the Marquis of Pombal, was a Portuguese despotic statesman and diplomat who effectively ruled the Portuguese Empire from 1750 to 1777 as chief minister to King Joseph I. A strong promoter of the absolute power and influenced by the Age of Enlightenment, Pombal led Portugal's recovery from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and reformed the kingdom's administrative, economic, and ecclesiastical institutions. During his lengthy ministerial career, Pombal accumulated and exercised autocratic power. His cruel persecution of the Portuguese lower classes led him to be known as Nero of Trafaria, a village he ordered to be burned with all its inhabitants inside, after refusing to follow his orders.

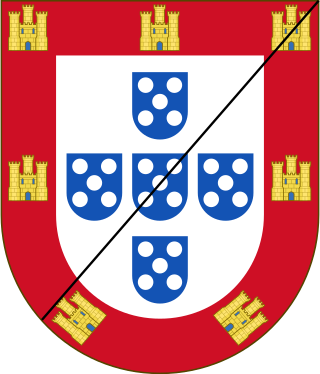

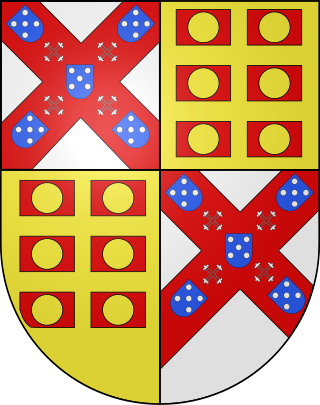

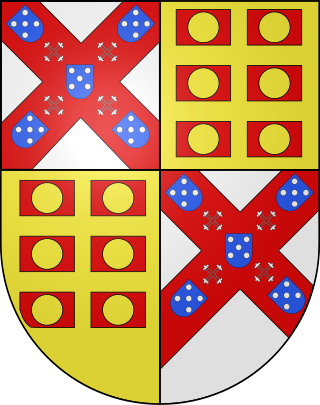

Duke of Aveiro was a Portuguese title of nobility, granted in 1535 by King John III of Portugal to his 4th cousin, John of Lencastre, son of Infante George of Lencastre, a natural son of King John II of Portugal.

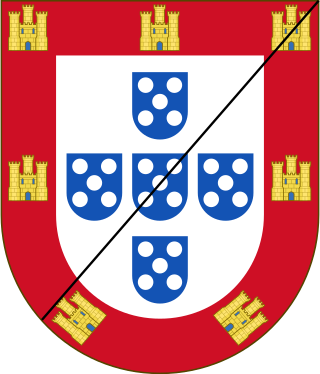

Count of Oeiras was a Portuguese title of nobility created by a royal decree, dated July 15, 1759, by King Joseph I of Portugal, and granted to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, Chief Minister of the Portuguese government.

From the House of Braganza restoration in 1640 until the end of the reign of the Marquis of Pombal in 1777, the Kingdom of Portugal was in a transition period. Having been near its height at the start of the Iberian Union, the Portuguese Empire continued to enjoy the widespread influence in the world during this period that had characterized the period of the Discoveries. By the end of this period, however, the fortunes of Portugal and its empire had declined, culminating with the Távora affair, the catastrophic 1755 Lisbon earthquake, and the accession of Maria I, the first ruling Queen of Portugal.

Gabriel Malagrida, SJ was an Italian Jesuit missionary in the Portuguese colony of Brazil and influential figure in the political life of the Lisbon Royal Court.

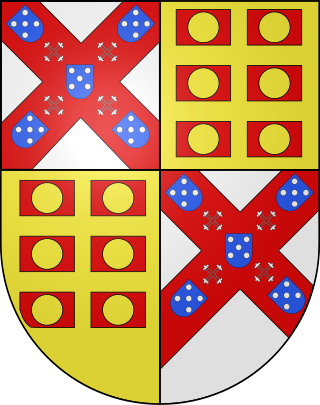

Count of Assumar was a Portuguese title of nobility granted, on 30 March 1630, by King Philip III of Portugal, to D. Francisco de Melo, son of Constantino de Bragança, a junior member of the House of Cadaval.

Marquis of Alorna was a Portuguese title of nobility granted, on 9 November 1748, by King John V of Portugal, to D. Pedro Miguel de Almeida Portugal e Vasconcelos, 3rd Count of Assumar and 44th viceroy of India.

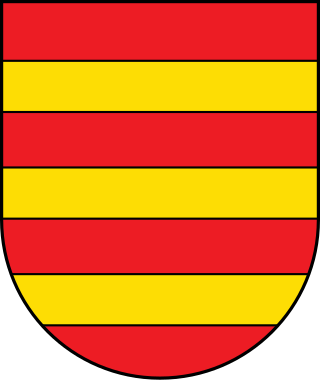

Count of Torre was a Portuguese title of nobility created by a royal decree, dated from July 26, 1638, by King Philip II of Portugal, and granted to Dom Fernando de Mascarenhas, Lord of Rosmaninhal.

Leonor Tomásia de Távora, 3rd Marchioness of Távora was a Portuguese noblewoman, most notable for being one of those executed by the Marquis of Pombal during the Távora affair.

Memory Church is a church in Ajuda (Lisbon), Portugal. It holds the Mausoleum of the Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal. It is classified as a National Monument.

D. Leonor de Almeida Portugal, 4th Marquise of Alorna, 8th Countess of Assumar was a Portuguese noblewoman, painter, and poet. Commonly known by her nickname, Alcipe, the Marquise was a prime figure in the Portuguese Neoclassic a proto-Romantic literary scene, while still a follower of Neoclassicism when it came to painting.

Santa Maria Maior is a freguesia and district of Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. Located in the historic center of Lisbon, Santa Maria Maior is to the west of São Vicente, east of Misericórdia, and south of Arroios and Santo António. It is home to numerous historic monuments, including Lisbon Cathedral, the Rossio, and the Praça do Comércio, as well as famous neighborhoods, such as the Lisbon Baixa, as well as parts of Bairro Alto and Alfama. The population in 2011 was 12,822,

Carlos Mardel was a Hungarian-Portuguese military officer, engineer, and architect. Mardel is primarily remembered for his role in the reconstruction effort after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.

O Processo dos Távoras is a historical fiction television series produced by RTP, Antinomia Produções Vídeo and the Institute of Cinema, Audiovisual and Multimedia (ICAM) in 2001. It was written by Francisco Moita Flores, based on the Portuguese political scandal that occurred during the reign of D. José, in 1758. The series had a prominent place at the International Television Festival in Venice 2002.

Eleonora Ernestina von Daun, Marquise of Pombal was the second wife of Portuguese statesman Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal.

José de Seabra da Silva, was a Portuguese magistrate and politician. He was Secretary of State during the rule of the Marquis of Pombal. He contributed to an anti-Jesuit treatise that was used to justify the expulsion of Jesuits from Portugal.

Paulo António de Carvalho e Mendonça (1702–1770) was a Portuguese priest and a cardinal, a court official who served as supervisor of the house and properties of Queen Mariana Vítoria, President of the Senate of Lisbon, a Canon of Lisbon Cathedral, Grand Prior of the College of Guimarães and Inquisitor-General of the Holy Inquisition.

Hospital de São José is a public Central Hospital serving the Greater Lisbon area as part of the Central Lisbon University Hospital Centre (CHULC), a state-owned enterprise.