The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and the use of force legitimized by the state via the monopoly on violence. The term is most commonly associated with the police forces of a sovereign state that are authorized to exercise the police power of that state within a defined legal or territorial area of responsibility. Police forces are often defined as being separate from the military and other organizations involved in the defense of the state against foreign aggressors; however, gendarmerie are military units charged with civil policing. Police forces are usually public sector services, funded through taxes.

Police perjury is the act of a police officer knowingly giving false testimony. It is typically used in a criminal trial to "make the case" against defendants believed by the police to be guilty when irregularities during the suspects' arrest or search threaten to result in their acquittal. It also can be extended to encompass substantive misstatements of fact to convict those whom the police believe to be guilty, procedural misstatements to "justify" a search and seizure, or even the inclusion of statements to frame an innocent citizen. More generically, it has been said to be "[l]ying under oath, especially by a police officer, to help get a conviction."

A private investigator, a private detective, or inquiry agent is a person who can be hired by individuals or groups to undertake investigatory law services. Private investigators often work for attorneys in civil and criminal cases.

A detective is an investigator, usually a member of a law enforcement agency. They often collect information to solve crimes by talking to witnesses and informants, collecting physical evidence, or searching records in databases. This leads them to arrest criminals and enable them to be convicted in court. A detective may work for the police or privately.

Eugène-François Vidocq was a French criminal turned criminalist, whose life story inspired several writers, including Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe and Honoré de Balzac. The former criminal became the founder and first director of the crime-detection Sûreté nationale as well as the head of the first known private detective agency. Vidocq is considered to be the father of modern criminology and of the French police department. He is also regarded as the first private detective.

A police officer is a warranted law employee of a police force. In most countries, "police officer" is a generic term not specifying a particular rank. In some, the use of the rank "officer" is legally reserved for military personnel.

The Sûreté du Québec is the provincial police service for the Canadian province of Quebec. No official English name exists, but the agency's name is sometimes translated to 'Quebec Provincial Police' or QPP in English-language sources. The headquarters of the Sûreté du Québec are located on Parthenais Street in Montreal's Sainte-Marie neighbourhood, and the service employs over 5,000 officers. The SQ is the second-largest provincial police service and the fourth-largest police service in Canada.

The police show, or police crime drama, is a subgenre of procedural drama and detective fiction that emphasizes the investigative procedure of a police officer or department as the protagonist(s), as contrasted with other genres that focus on either a private detective, an amateur investigator or the characters who are the targets of investigations. While many police procedurals conceal the criminal's identity until the crime is solved in the narrative climax, others reveal the perpetrator's identity to the audience early in the narrative, making it an inverted detective story. Whatever the plot style, the defining element of a police procedural is the attempt to accurately depict the profession of law enforcement, including such police-related topics as forensic science, autopsies, gathering evidence, search warrants, interrogation and adherence to legal restrictions and procedure.

An agent provocateur is a person who commits, or who acts to entice another person to commit, an illegal or rash act or falsely implicate them in partaking in an illegal act, so as to ruin the reputation of, or entice legal action against, the target, or a group they belong to or are perceived to belong to. They may target any group, such as a peaceful protest or demonstration, a union, a political party or a company.

Sûreté is, in many French-speaking countries or regions, the organizational title of a civil police force, especially the detective branch thereof.

Kriminalpolizei is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal police department for the entire Reich. Today, in the Federal Republic of Germany, the state police (Landespolizei) perform the majority of investigations. Its Criminal Investigation Department is known as the Kriminalpolizei or more colloquially, the Kripo.

Inspector, also police inspector or inspector of police, is a police rank. The rank or position varies in seniority depending on the organization that uses it.

The United States Army Criminal Investigation Division (USACID), previously known as the United States Army Criminal Investigation Command (USACIDC) is the primary federal law enforcement agency of the United States Department of the Army. Its primary function is to investigate felony crimes and serious violations of military law & the United States Code within the US Army. The division is a separate military investigative force with investigative autonomy; CID special agents, both military and civilian, report through the CID chain of command to the USACID Director, who reports directly to the Under Secretary of the Army and the Secretary of the Army. Unlike their counterparts at OSI, NCIS and CGIS, Army CID does not have primary counterintelligence responsibilities.

SEPTA Transit Police is an American law enforcement agency, which is responsible for policing the mass transit system that is operated by the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The police department also operates in the adjacent suburban areas of Delaware, Montgomery, Chester, and Bucks counties in Pennsylvania, and covers transit routes that extend into the states of New Jersey and Delaware.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to law enforcement:

Covert policing in the United Kingdom are the practices of the British police that are hidden to the public, usually employed in order that an officer can gather intelligence and approach an offender without prompting escape.

The color of the day is a signal used by plainclothes officers of some police departments in the United States. It is used to assist in the identification of plainclothes police officers by those in uniform. It is used by the New York City Police Department and other law enforcement agencies.

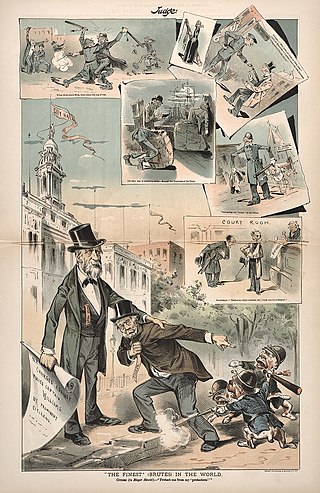

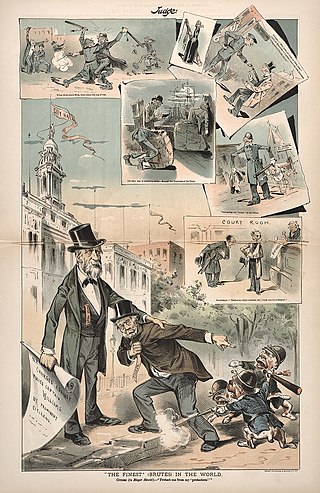

Throughout the history of the New York City Police Department, numerous instances of corruption and misconduct, and allegations of such, have occurred. Over 12,000 cases have resulted in lawsuit settlements totaling over $400 million during a five-year period ending in 2014. In 2019, taxpayers funded $68,688,423 as the cost of misconduct lawsuits, a 76 percent increase over the previous year, including about $10 million paid out to two exonerated individuals who had been falsely convicted and imprisoned.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs Police, Office of Justice Services, also known as BIA Police, is the law enforcement arm of the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. The BIA's official mission is to "uphold the constitutional sovereignty of the Federally recognized Tribes and preserve peace within Indian country". It provides police, investigative, corrections, technical assistance, and court services across the over 567 registered Indian tribes and reservations, especially those lacking their own police force; additionally, it oversees tribal police organizations. BIA services are provided through the Office of Justice Services Division of Law Enforcement.

The National Surveillance Unit (NSU) is the principal clandestine intelligence gathering and surveillance operations unit of the Garda Síochána, the national police force of Ireland. The unit operates under the Crime & Security Branch (CSB), based at Garda Headquarters in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, and also works from Harcourt Street, Dublin. Members of the unit are specially trained and selected Detective Gardaí who are tasked to remain covert whilst on and off duty, tracking suspected criminals, terrorists and hostile, foreign spies operating in Ireland. The unit's detectives are routinely armed. The National Surveillance Unit is understood to possess a manpower of approximately 100 officers, and is considered to be the most secretive arm of the force.