Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontological property of being.

A proposition is a central concept in philosophy of language and related fields, often characterized as the primary bearer of truth or falsity. Propositions are also often characterized as being the kind of thing that declarative sentences denote. For instance the sentence "The sky is blue" denotes the proposition that the sky is blue. However, crucially, propositions are not themselves linguistic expressions. For instance, the English sentence "Snow is white" denotes the same proposition as the German sentence "Schnee ist weiß" even though the two sentences are not the same. Similarly, propositions can also be characterized as the objects of belief and other propositional attitudes. For instance if one believes that the sky is blue, what one believes is the proposition that the sky is blue.

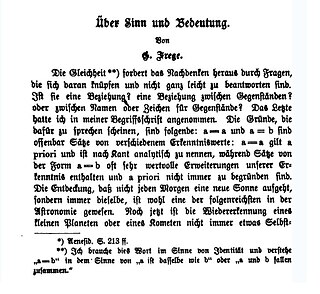

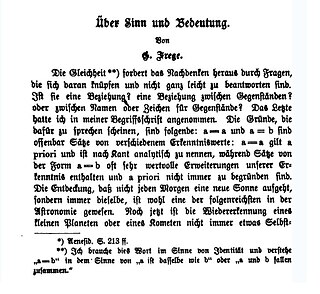

In the philosophy of language, the distinction between sense and reference was an idea of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottlob Frege in 1892, reflecting the two ways he believed a singular term may have meaning.

In metaphysics and the philosophy of language, an empty name is a proper name that has no referent.

In the philosophy of language, the distinction between concept and object is attributable to the German philosopher Gottlob Frege in 1892.

In philosophy, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, the Peripatetics. It was revived after the third century CE by Porphyry's Isagoge.

In the philosophy of mathematics, logicism is a programme comprising one or more of the theses that — for some coherent meaning of 'logic' — mathematics is an extension of logic, some or all of mathematics is reducible to logic, or some or all of mathematics may be modelled in logic. Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead championed this programme, initiated by Gottlob Frege and subsequently developed by Richard Dedekind and Giuseppe Peano.

In philosophy and logic, a deflationary theory of truth is one of a family of theories that all have in common the claim that assertions of predicate truth of a statement do not attribute a property called "truth" to such a statement.

De Interpretatione or On Interpretation is the second text from Aristotle's Organon and is among the earliest surviving philosophical works in the Western tradition to deal with the relationship between language and logic in a comprehensive, explicit, and formal way. The work is usually known by its Latin title.

The theory of descriptions is the philosopher Bertrand Russell's most significant contribution to the philosophy of language. It is also known as Russell's theory of descriptions. In short, Russell argued that the syntactic form of descriptions is misleading, as it does not correlate their logical and/or semantic architecture. While descriptions may seem fairly uncontroversial phrases, Russell argued that providing a satisfactory analysis of the linguistic and logical properties of a description is vital to clarity in important philosophical debates, particularly in semantic arguments, epistemology and metaphysical elements.

In logic, the law of identity states that each thing is identical with itself. It is the first of the historical three laws of thought, along with the law of noncontradiction, and the law of excluded middle. However, few systems of logic are built on just these laws.

According to the redundancy theory of truth, asserting that a statement is true is completely equivalent to asserting the statement itself. For example, asserting the sentence "'Snow is white' is true" is equivalent to asserting the sentence "Snow is white". The philosophical redundancy theory of truth is a deflationary theory of truth.

In the philosophy of language, the descriptivist theory of proper names is the view that the meaning or semantic content of a proper name is identical to the descriptions associated with it by speakers, while their referents are determined to be the objects that satisfy these descriptions. Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege have both been associated with the descriptivist theory, which is sometimes called the mediated reference theory or Frege–Russell view.

In semantics, semiotics, philosophy of language, metaphysics, and metasemantics, meaning "is a relationship between two sorts of things: signs and the kinds of things they intend, express, or signify".

A truth-bearer is an entity that is said to be either true or false and nothing else. The thesis that some things are true while others are false has led to different theories about the nature of these entities. Since there is divergence of opinion on the matter, the term truth-bearer is used to be neutral among the various theories. Truth-bearer candidates include propositions, sentences, sentence-tokens, statements, beliefs, thoughts, intuitions, utterances, and judgements but different authors exclude one or more of these, deny their existence, argue that they are true only in a derivative sense, assert or assume that the terms are synonymous, or seek to avoid addressing their distinction or do not clarify it.

The analytic–synthetic distinction is a semantic distinction, used primarily in philosophy to distinguish between propositions that are of two types: analytic propositions and synthetic propositions. Analytic propositions are true or not true solely by virtue of their meaning, whereas synthetic propositions' truth, if any, derives from how their meaning relates to the world.

In analytic philosophy, philosophy of language investigates the nature of language and the relations between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of meaning, intentionality, reference, the constitution of sentences, concepts, learning, and thought.

Bradley's regress is a philosophical problem concerning the nature of relations. It is named after F. H. Bradley who discussed the problem in his 1893 book Appearance and Reality. It bears a close kinship to the issue of the unity of the proposition.

The mathematical concept of a function emerged in the 17th century in connection with the development of the calculus; for example, the slope of a graph at a point was regarded as a function of the x-coordinate of the point. Functions were not explicitly considered in antiquity, but some precursors of the concept can perhaps be seen in the work of medieval philosophers and mathematicians such as Oresme.

Predication in philosophy refers to an act of judgement where one term is subsumed under another. A comprehensive conceptualization describes it as the understanding of the relation expressed by a predicative structure primordially through the opposition between particular and general or the one and the many.