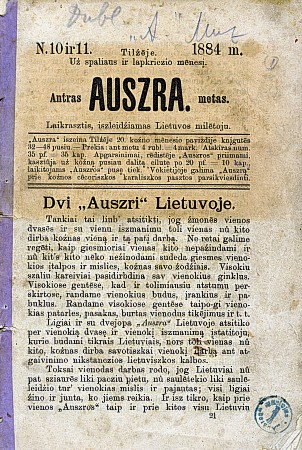

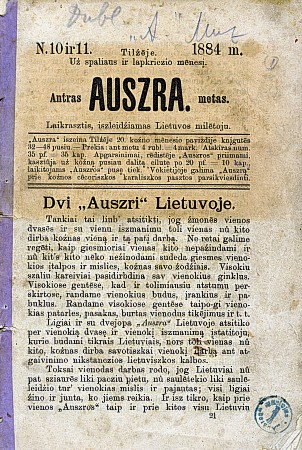

Aušra or Auszra was the first national Lithuanian newspaper. The first issue was published in 1883, in Ragnit, East Prussia, Germany East Prussia's ethnolinguistic part - Lithuania Minor. Later it was published monthly in Tilsit. Even though only forty issues were published and the circulation did not exceed 1,000, it was a significant event as it marked the beginnings of the Lithuanian national rebirth that eventually resulted in an independent Lithuanian State (1918–1940). This period, between 1883 and 1904, when the Lithuanian press ban was enforced by Tsarist authorities, has been referred to as the Aušros gadynė. The printing ceased in 1886 as a result of financial issues.

Vincas Mickevičius, known under his pen name Kapsukas, was a Lithuanian communist political activist, publicist and revolutionary.

Juozas Adomaitis known by his pen name Šernas (1859–1922) was a Lithuanian non-fiction writer. He contributed to the Lithuanian-language newspapers Aušra and briefly served as editor of Varpas. In 1895, he moved to the United States where he worked as editor of the Lithuanian weekly Lietuva. He published about 20 popular science books about biology, ethnology, geography, history of writing.

Povilas Višinskis was a Lithuanian cultural and political activist during the Lithuanian National Revival. He is best remembered as a mentor of literary talent. He discovered Julija Žymantienė (Žemaitė) and advised Marija Pečkauskaitė, Sofija Pšibiliauskienė, Gabrielė Petkevičaitė (Bitė), Jonas Biliūnas, Jonas Krikščiūnas (Jovaras), helping them edit and publish their first works.

Gabrielė Petkevičaitė was a Lithuanian educator, writer, and activist. Her pen name Bitė (Bee) eventually became part of her last name. Encouraged by Povilas Višinskis, she joined public life and started her writing career in 1890, becoming a prominent member of the Lithuanian National Revival. She was the founder and chair of the Žiburėlis society to provide financial aid to struggling students, one of the editors of the newspaper Lietuvos žinios, and an active member of the women's movement. In 1920, she was elected to the Constituent Assembly of Lithuania and chaired its first session. Her realist writing centered on exploring the negative impact of the social inequality. Her largest work, two-part novel Ad astra (1933), depicts the rising Lithuanian National Revival. Together with Žemaitė, she co-wrote several plays. Her diary, kept during World War I, was published in 1925–1931 and 2008–2011.

Šviesa or Szviesa was a short-lived Lithuanian-language newspaper printed during the Lithuanian press ban in Tilsit in German East Prussia and smuggled to Lithuania by the knygnešiai. The monthly newspaper was published from August 1887 to August 1888 and from January to August 1890. 50- to 32-page newspaper had circulation of about 1,000. A special 72-page supplement was published in 1888. Influence of Šviesa was not very significant as it did not last and did not offer new ideas.

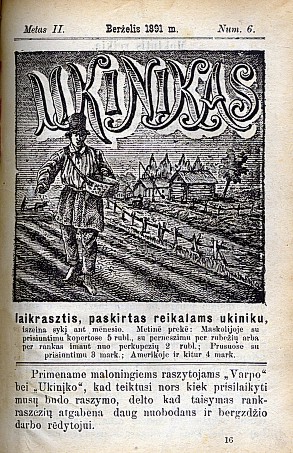

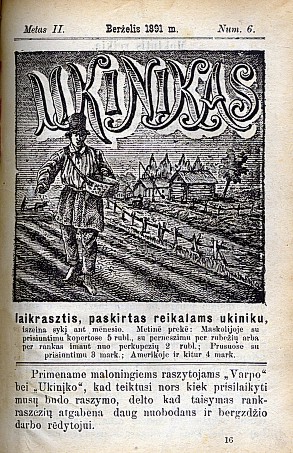

Ūkininkas or Ukinįkas was a monthly Lithuanian-language newspaper published during the Lithuanian press ban by the editorial staff of Varpas from 1890 to 1905. Ūkininkas was printed in Tilsit and Ragnit in German East Prussia and smuggled into Lithuania by the knygnešiai.

Naujienos was a short-lived Lithuanian-language monthly newspaper published by editorial staff of Varpas and Ūkininkas. Due to the Lithuanian press ban in the Russian Empire, the newspaper was published in Tilsit in East Prussia and then smuggled to Lithuania by knygnešiai. In 1903, its circulation was around 1,500.

Marijampolė Rygiškių Jonas Gymnasium is a secondary school in Marijampolė, Lithuania. It is named after Rygiškių Jonas, one of the pen names of linguist Jonas Jablonskis who was one of the gymnasium's alumni. Established in 1867, the gymnasium was a significant cultural center of Suvalkija and educated many prominent figures of the Lithuanian National Revival. Since 2010, it is a four-year school.

Žiburėlis later Lietuvos žiburėlis was a charitable society providing financial aid to gifted Lithuanian students. The society grew out of the Lithuanian National Revival, hopes of creating Lithuanian intelligentsia, and frustration over financial hardships faced by many young students. It was established in 1893 by Gabrielė Petkevičaitė-Bitė and Jadvyga Juškytė, and led by Felicija Bortkevičienė from 1903 until its dissolution in 1940.

Lietuvos ūkininkas was a weekly Lithuanian-language newspaper published between 1905 and 1940. It was published by and reflected the political views of the Lithuanian Democratic Party, Peasant Union, and Lithuanian Peasant Popular Union. Its printing and daily operations were managed by its long-time publisher Felicija Bortkevičienė. It was a liberal publication geared towards the wider audience of less educated farmers and peasants. In 1933, its circulation was 15,000 copies. When Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940, the newspaper was nationalized and replaced by Valstiečių laikraštis.

Petras Avižonis was a Lithuanian ophthalmologist, rector of the University of Lithuania (1925–1926) and a political figure.

Žemaičių ir Lietuvos apžvalga, often abbreviated as Apžvalga, was a Lithuanian-language Catholic newspaper published in Tilsit, East Prussia, in 1889–1896. At the time, Lithuanian press was banned and the newspaper had to be smuggled across the Prussia–Russia border. It promoted and supported the Lithuanian National Revival, but above all defended the Catholic faith. While it was fiercely anti-Tsarist publication when it came to religious and cultural topics, it was a socially conservative publication. It was replaced by a relatively more liberal Tėvynės sargas established in 1896.

Lietuviškasis balsas was a Lithuanian-language newspaper published by Jonas Šliūpas from July 1885 to February 1889 in New York City and Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. It promoted the Lithuanian National Revival. Due to financial difficulties, it appeared irregularly. It competed with pro-Polish and pro-Catholic Vienybė lietuvninkų and was discontinued after 96 issues in early 1889. The competition and ideological debate between the two newspapers identified the two main branches of the Lithuanian movement – rationalist nationalists and conservative Catholics.

Petras Kriaučiūnas (1850–1916) was an activist during the Lithuanian National Revival. Educated as a priest, he taught at the Marijampolė Gymnasium in 1881–1887 and 1906–1914 and was active as an amateur linguist.

America in the Bathhouse is a three-act comedy by Keturakis. The play was first published in 1895. It became the first Lithuanian-language play performed in public in present-day Lithuania when a group of Lithuanian activists staged it on 20 August 1899 in Palanga. The play depicts an episode from the everyday life of the Lithuanian village – a resourceful man swindles money from a naive woman and escapes to the United States. Due to its relevant plot, small cast, and simple decorations, the play was very popular with the Lithuanian amateur theater. It became one of the most popular and successful Lithuanian comedies of all time and continues to be performed by various troupes.

Jonas Kriaučiūnas was a Lithuanian activist during the Lithuanian National Revival mostly noted for editing and publishing Lithuanian periodicals Varpas and Ūkininkas in 1891–1895 and Vilniaus žinios in 1905–1906.

Jadvyga Teofilė Juškytė (1869–1948) was a Lithuanian activist during the Lithuanian National Revival.

Graf Vladimir Zubov was a liberal nobleman from the Russian Zubov family who supported the Lithuanian National Revival.

Darbininkų balsas was a Lithuanian newspaper published by the Social Democratic Party of Lithuania from July 1901 to April 1906. It was the first more stable Lithuanian periodical of the party. The publication was illegal in the Russian Empire because of its political content and because it was in Lithuanian. Therefore, the newspaper was printed in East Prussia and smuggled into Lithuania. After the Russian Revolution of 1905, the newspaper was replaced by the legal Naujoji Gadynė published in Vilnius.