Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the water, on ice (iceboat) or on land over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation.

A match race is a race between two competitors, going head-to-head.

Apparent wind is the wind experienced by a moving object.

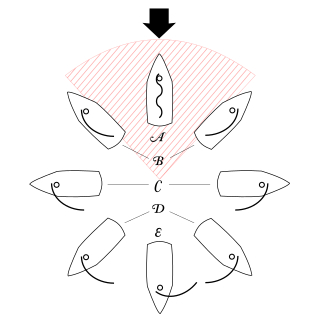

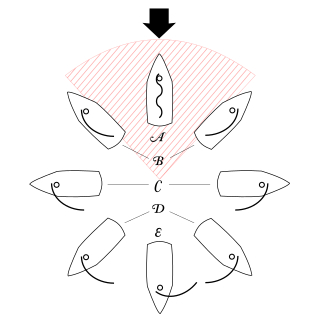

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

A jibe (US) or gybe (Britain) is a sailing maneuver whereby a sailing craft reaching downwind turns its stern through the wind, which then exerts its force from the opposite side of the vessel. It stands in contrast with tacking, whereby the sailing craft turns its bow through the wind.

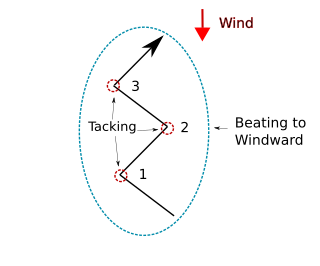

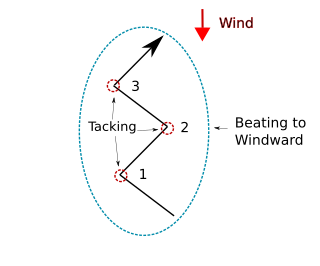

Tacking or coming about is a sailing maneuver by which a sailing craft, whose next destination is into the wind, turns its bow toward and through the wind so that the direction from which the wind blows changes from one side of the boat to the other, allowing progress in the desired direction. Sailing vessels are unable to sail higher than a certain angle towards the wind, so "beating to windward" in a zig-zag fashion with a series of tacking maneuvers, allows a vessel to sail towards a destination that is closer to the wind than the vessel can sail directly.

A lubber line, also known as a lubber's line, is a fixed line on a compass binnacle or radar plan position indicator display pointing towards the front of the ship or aircraft and corresponding to the craft's centerline.

In sailing, luffing refers to when a sailing vessel is steered far enough toward the direction of the wind ("windward"), or the sheet controlling a sail is eased so far past optimal trim, that airflow over the surfaces of the sail is disrupted and the sail begins to "flap" or "luff". This is not always done in error; for example, the sails will luff when the bow of the boat passes through the direction of the wind as the sailboat is tacked.

A fractional rig on a sailing vessel consists of a foresail, such as a jib or genoa sail, that does not reach all the way to the top of the mast.

Self-steering gear is equipment used on sail boats to maintain a chosen course or point of sail without constant human action.

A following sea refers to a wave direction that is similar to the heading of a waterborne vessel under way. The word "sea" in this context refers to open water wind waves.

Sailing into the wind is a sailing expression that refers to a sail boat's ability to move forward despite being headed into the wind. A sailboat cannot make headway by sailing directly into the wind ; the point of sail into the wind is called "close hauled".

Wind-powered vehicles derive their power from sails, kites or rotors and ride on wheels—which may be linked to a wind-powered rotor—or runners. Whether powered by sail, kite or rotor, these vehicles share a common trait: As the vehicle increases in speed, the advancing airfoil encounters an increasing apparent wind at an angle of attack that is increasingly smaller. At the same time, such vehicles are subject to relatively low forward resistance, compared with traditional sailing craft. As a result, such vehicles are often capable of speeds exceeding that of the wind.

USA-17 is a sloop rigged racing trimaran built by the American sailing team BMW Oracle Racing to challenge for the 2010 America's Cup. Designed by VPLP Yacht Design with consultation from Franck Cammas and his Groupama multi-hull sailing team, BOR90 is very light for her size being constructed almost entirely out of carbon fiber and epoxy resin, and exhibits very high performance being able to sail at 2.0 to 2.5 times the true wind speed. From the actual performance of the boat during the 2010 America's Cup races, it can be seen that she could achieve a velocity made good upwind of over twice the wind speed and downwind of over 2.5 times the wind speed. She can apparently sail at 20 degrees off the apparent wind. The boat sails so fast downwind that the apparent wind she generates is only 5-6 degrees different from that when she is racing upwind; that is, the boat is always sailing upwind with respect to the apparent wind. An explanation of this phenomenon can be found in the article on sailing faster than the wind.

High-performance sailing is achieved with low forward surface resistance—encountered by catamarans, sailing hydrofoils, iceboats or land sailing craft—as the sailing craft obtains motive power with its sails or aerofoils at speeds that are often faster than the wind on both upwind and downwind points of sail. Faster-than-the-wind sailing means that the apparent wind angle experienced on the moving craft is always ahead of the sail. This has generated a new concept of sailing, called "apparent wind sailing", which entails a new skill set for its practitioners, including tacking on downwind points of sail.

The 34th America's Cup was a series of yacht races held in San Francisco Bay in September 2013. The series was contested between the defender Oracle Team USA team representing the Golden Gate Yacht Club, and the challenger Emirates Team New Zealand representing the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron. The format was changed radically to a best of 17, and Oracle Team USA defended the America's Cup by a score of 9 to 8 after Team New Zealand had built an 8 to 1 lead. Team New Zealand won the right to challenge for the Cup by previously winning the 2013 Louis Vuitton Cup. The 34th America's Cup's race schedule was the longest ever, in terms of number of days and number of races, and the first since the 25th America's Cup to feature both teams in a match point situation.

Forces on sails result from movement of air that interacts with sails and gives them motive power for sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and sail-powered land vehicles. Similar principles in a rotating frame of reference apply to windmill sails and wind turbine blades, which are also wind-driven. They are differentiated from forces on wings, and propeller blades, the actions of which are not adjusted to the wind. Kites also power certain sailing craft, but do not employ a mast to support the airfoil and are beyond the scope of this article.

SailTimer is a technology for sailboat navigation, which calculates optimal tacking angles, distances and times.

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may be made from a combination of woven materials—including canvas or polyester cloth, laminated membranes or bonded filaments, usually in a three- or four-sided shape.

The lug sail, or lugsail, is a fore-and-aft, four-cornered sail that is suspended from a spar, called a yard. When raised, the sail area overlaps the mast. For "standing lug" rigs, the sail may remain on the same side of the mast on both the port and starboard tacks. For "dipping lug" rigs, the sail is lowered partially or totally to be brought around to the leeward side of the mast in order to optimize the efficiency of the sail on both tacks.