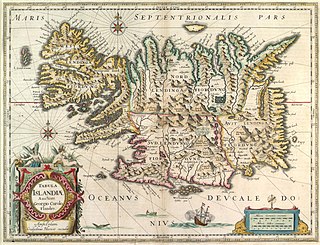

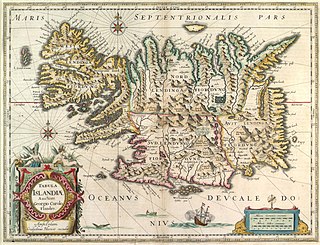

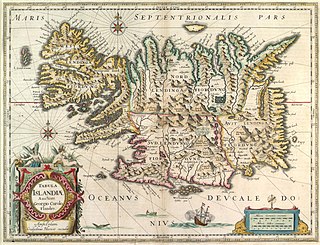

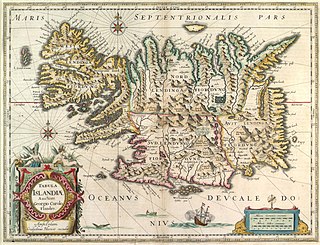

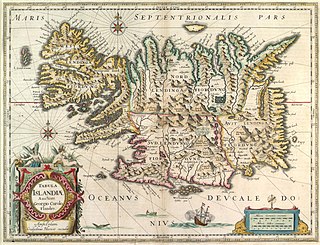

The recorded history of Iceland began with the settlement by Viking explorers and the people they enslaved from Western Europe, particularly in modern-day Norway and the British Isles, in the late ninth century. Iceland was still uninhabited long after the rest of Western Europe had been settled. Recorded settlement has conventionally been dated back to 874, although archaeological evidence indicates Gaelic monks from Ireland, known as papar according to sagas, may have settled Iceland earlier.

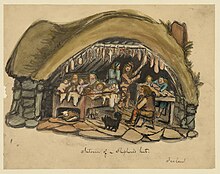

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants existed: non-free slaves, semi-free serfs, and free tenants. Peasants might hold title to land outright, or by any of several forms of land tenure, among them socage, quit-rent, leasehold, and copyhold.

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed during the Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in Europe and lasted in some countries until the mid-19th century.

The culture of Iceland is largely characterized by its literary heritage that began during the 12th century but also traditional arts such as weaving, silversmithing, and wood carving. The Reykjavík area hosts several professional theaters, art galleries, bookstores, cinemas and museums. There are four active folk dance ensembles in Iceland. Iceland's literacy rate is among the highest in the world.

Hannes Þórður Pétursson Hafstein was an Icelandic politician and poet. In 1904 he became the first Icelander to be appointed to the Danish Cabinet as the minister for Iceland in the Cabinet of Deuntzer and was – unlike the previous minister for Iceland Peter Adler Alberti – responsible to the Icelandic Althing.

Þjóðernishyggja is the Icelandic term for nationalism; nationmindedness is a rough translation of the term. Its use was instrumental in the Icelandic movement for independence from Denmark, led by Jón Sigurðsson.

Independent People: An Epic is a novel by Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness, originally published in two volumes in 1934 and 1935. It deals with the struggle of poor Icelandic farmers in the early 20th century, only freed from debt bondage in the last generation, and surviving on isolated crofts in an inhospitable landscape.

Jón Sigurðsson was the leader of the 19th century Icelandic independence movement.

The Old Covenant was the name of the agreement which effected the union of Iceland and Norway. It is also known as Gissurarsáttmáli, named after Gissur Þorvaldsson, the Icelandic chieftain who worked to promote it. The name "Old Covenant", however, is probably due to historical confusion. Gamli sáttmáli is properly the treaty of 1302 mentioned below and the treaty of 1262 is the actual Gissurarsáttmáli.

The Turra Coo was a white Ayrshire-Shorthorn cross dairy cow which lived near the Aberdeenshire town of Turriff in north-east Scotland in the early twentieth century. The cow became famous following a dispute between her owner, supported by local people, against the government over taxes and compulsory national insurance.

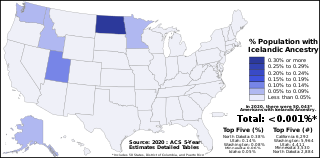

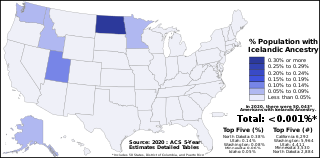

Icelandic Americans are Americans of Icelandic descent or Iceland-born people who reside in the United States. Icelandic immigrants came to the United States primarily in the period 1873–1905 and after World War II. There are more than 40,000 Icelandic Americans according to the 2000 U.S. census, and most live in the Upper Midwest. The United States is home to the second largest Icelandic diaspora community in the world after Canada.

The cuisine of Iceland has a long history. Important parts of Icelandic cuisine are lamb, dairy, and fish, the latter due to the fact that Iceland has traditionally been inhabited only near its coastline. Popular foods in Iceland include skyr, hangikjöt, kleinur, laufabrauð, and bollur. Þorramatur is a traditional buffet served at midwinter festivals called Þorrablót; it includes a selection of traditionally cured meat and fish products served with rúgbrauð and brennivín. The flavors of this traditional country food originate in its preservation methods: pickling in fermented whey or brine, drying, and smoking.

Capital punishment in Iceland was practiced until 1830, with 240 individuals executed between 1551 and 1830. Methods included beheading, hanging, burning, and drowning. Danish laws were influential, particularly after Lutheranism's adoption in the 17th century. The last execution occurred in 1830, and the death penalty was abolished in 1928. Infanticide was a common crime, often committed by women, and many were sentenced to death, but their sentences were commuted. The last execution of an Icelander happened in Denmark in 1913. The death penalty was officially abolished in Iceland in 1928, and its reintroduction has been unconstitutional since a 1995 constitutional revision.

A constitutional referendum was held in Iceland between 20 and 23 May 1944. The 1 December 1918 Danish–Icelandic Act of Union declared Iceland to be a sovereign state separate from Denmark, but maintained the two countries in a personal union, with the King of Denmark also being the King of Iceland. In the two-part referendum, voters were asked whether the Union with Denmark should be abolished, and whether to adopt a new republican constitution. Both measures were approved, each with more than 98% in favour. Voter turnout was 98.4% overall, and 100% in two constituencies, Seyðisfirði and Vestur-Skaftafjellssýsla.

Norwegian serfdom can be a way of defining the position of the Norwegian lower class farmers, though they were not actually in serfdom by European standards. The evolution of this social system began about 1750.

The Icelandic Independence movement was the collective effort made by Icelanders to achieve self-determination and independence from the Kingdom of Denmark throughout the 19th and early 20th century.

The economy history of Iceland covers the development of its economy from the Settlement of Iceland in the late 9th century until the present.

The Stavnsbånd was a serfdom-like institution introduced in Denmark in 1733 in accordance with the wishes of estate owners and the military. It bonded men between the ages of 14 and 36 to live on the estate where they were born. It was possible, however, to purchase a pass releasing one from this bondage. So, in practice, estate owners and their sons were not particularly bonded to live on their estates.

Jónas Jónsson was an Icelandic educator and politician, and one of the most influential people in 20th-century Icelandic culture and politics. Initially an educator and writer of textbooks, he was chairman of the Progressive Party for ten years, and Minister of Justice from 1927 to 1932.

Anarchism in Latvia emerged from the Latvian National Awakening and saw its apex during the 1905 Russian Revolution. Eventually the Latvian anarchist movement was suppressed by a series of authoritarian regimes in the country.