Seville is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Carmona is a town of southwestern Spain, in the province of Seville; it lies 33 km north-east of Seville.

The Torre del Oro is a dodecagonal military watchtower in Seville, southern Spain. It was erected by the Almohad Caliphate in order to control access to Seville via the Guadalquivir river.

The Alcázar of Seville, officially called Royal Alcázar of Seville, is a historic royal palace in Seville, Spain. It was formerly the site of the Islamic-era citadel of the city, begun in the 10th century and then developed into a larger palace complex by the Abbadid dynasty and the Almohads. After the Castilian conquest of the city in 1248, the site was progressively rebuilt and replaced by new palaces and gardens. Among the most important of these is a richly-decorated Mudéjar-style palace built by Pedro I during the 1360s.

Santa Cruz, is the primary tourist neighborhood of Seville, Spain, and the former Jewish quarter of the medieval city. Santa Cruz is bordered by the Jardines de Murillo, the Real Alcázar, Calle Mateos Gago, and Calle Santa María La Blanca/San José. The neighbourhood is the location of many of Seville's oldest churches and is home to the Cathedral of Seville, including the converted minaret of the old Moorish mosque Giralda.

Macarena is one of the eleven districts into which the city of Seville, capital of the autonomous community of Andalucía, Spain, is divided for administrative purposes. It is located in the north of the city, bordered to the south by the Casco Antiguo and San Pablo-Santa Justa suburbs, to the east and north by Norte and to the west by Triana. It covers the area between the Guadalquivir River and the Carmona Highway and from the SE-30 ring-road in the north to the Ronda del Casco Antiguo. It contains smaller neighbourhoods such as León XIII, Miraflores, and the Polígono Norte as well as the Miraflores park along the SE-30. The district contains the Andalucian Parliament, the Torre de los Perdigones in the park of the same name, and the Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena

The Casco Antiguo is the city centre district of Seville, the capital of the Spanish region of Andalusia. The Casco Antiguo comprises Seville's old town, which lies on the east bank of the Guadalquivir river. It borders the districts of Macarena to the north, Nervión and San Pablo-Santa Justa to the east, and the Distrito Sur to the south. Bridges across the Guadalquivir link the Casco Antiguo to Los Remedios, Triana and La Cartuja.

Almohad architecture corresponds to a period from the 12th to early 13th centuries when the Almohads ruled over the western Maghreb and al-Andalus. It was an important phase in the consolidation of a regional Moorish architecture shared across these territories, continuing some of the trends of the preceding Almoravid period and of Almoravid architecture.

Seville, the capital of the region of Andalusia in Spain, has 11 districts, further divided into 108 neighbourhoods.

The history of Carmona begins at one of the oldest urban sites in Europe, with nearly five thousand years of continuous occupation on a plateau rising above the vega (plain) of the River Corbones in Andalusia, Spain. The city of Carmona lies thirty kilometres from Seville on the highest elevation of the sloping terrain of the Los Alcores escarpment, about 250 metres above sea level. Since the first appearance of complex agricultural societies in the Guadalquivir valley at the beginning of the Neolithic period, various civilizations have had an historical presence in the region. All the different cultures, peoples, and political entities that developed there have left their mark on the ethnographic mosaic of present-day Carmona. Its historical significance is explained by the advantages of its location. The easily defended plateau on which the city sits, and the fertility of the land around it, made the site an important population center. The town's strategic position overlooking the vega was a natural stronghold, allowing it to control the trails leading to the central plateau of the Guadalquivir valley, and thus access to its resources.

There are numerous sights and landmarks of Seville, Spain. The most important sights are the Alcázar, the Seville Cathedral, and the Archivo General de Indias, which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The historic centre of Córdoba, Spain is one of the largest of its kind in Europe. In 1984, UNESCO registered the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba as a World Heritage Site. A decade later, it expanded the inscription to include much of the old town. The historic centre has a wealth of monuments preserving large traces of Roman, Islamic, and Christian times.

The Seville Shipyard is a medieval shipyard in the city of Seville that operated from the 13th century to the 15th century. Composed of seventeen naves, the building was connected to the Guadalquivir River by a stretch of sand.

The Muslim Walls of Madrid, of which some vestiges remain, are located in the Spanish capital city of Madrid. They are probably the oldest construction extant in the city. They were built in the 9th century, during the Muslim domination of the Iberian Peninsula, on a promontory next to Manzanares river. They were part of a fortress around which developed the urban nucleus of Madrid. They were declared an Artistic-Historic Monument in 1954.

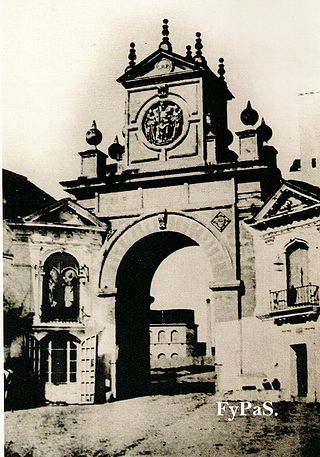

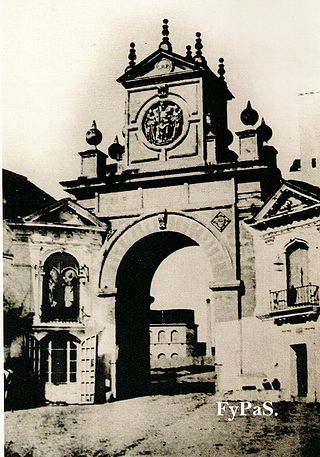

The Puerta de la Macarena, also known as Arco de la Macarena, is one of the only three city gates that remain today of the original walls of Seville, alongside the Postigo del Aceite and the Puerta de Córdoba. It is located in the calle Resolana, within the barrio de San Gil, which belongs to the district of Casco Antiguo of the city of Seville, in Andalusia, Spain. The gate faces the Basílica de La Macarena, which houses the image of the Our Lady of la Esperanza Macarena, one of the most characteristic images of the Holy Week in Seville.

The Postigo del Aceite is with the Puerta de la Macarena and Puerta de Córdoba the only three access preserved in today of those who had the walls of Seville, Andalusia, Spain.

The Puerta Real, called until 1570 as Puerta de Goles, was one of the gates of the walled enclosure of the city of Seville (Andalusia). It was located at the confluence of the calles de Alfonso XII, Gravina, Goles and San Laureano, and today only is it a cloth of the wall on which it was based, in which there is embedded a stone that was part of the gate.

The Puerta de Triana was the generic name for an Almohad gate which was later on replaced by a Christian gate at the same place. It was one of the gates of the walled enclosure of Seville (Andalusia).

Old Town of Cáceres is a historic walled city in Cáceres, Spain.