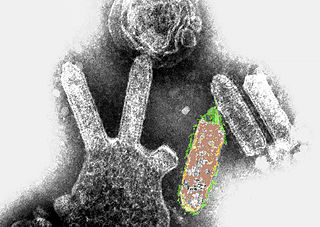

Indiana vesiculovirus, formerly Vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus is a virus in the family Rhabdoviridae; the well-known Rabies lyssavirus belongs to the same family. VSIV can infect insects, cattle, horses and pigs. It has particular importance to farmers in certain regions of the world where it infects cattle. This is because its clinical presentation is identical to the very important foot and mouth disease virus.

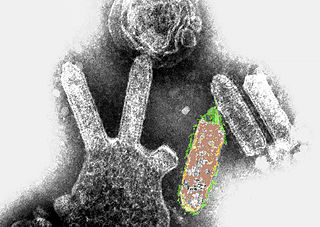

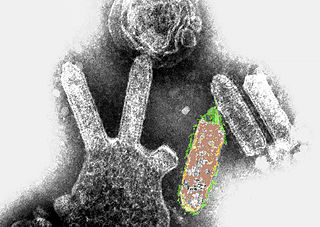

Rhabdoviridae is a family of negative-strand RNA viruses in the order Mononegavirales. Vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, fungi and protozoans serve as natural hosts. Diseases associated with member viruses include rabies encephalitis caused by the rabies virus, and flu-like symptoms in humans caused by vesiculoviruses. The name is derived from Ancient Greek rhabdos, meaning rod, referring to the shape of the viral particles. The family has 40 genera, most assigned to three subfamilies.

Mononegavirales is an order of negative-strand RNA viruses which have nonsegmented genomes. Some members that cause human disease in this order include Ebola virus, human respiratory syncytial virus, measles virus, mumps virus, Nipah virus, and rabies virus. Important pathogens of nonhuman animals and plants are also in the group. The order includes eleven virus families: Artoviridae, Bornaviridae, Filoviridae, Lispiviridae, Mymonaviridae, Nyamiviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Pneumoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Sunviridae, and Xinmoviridae.

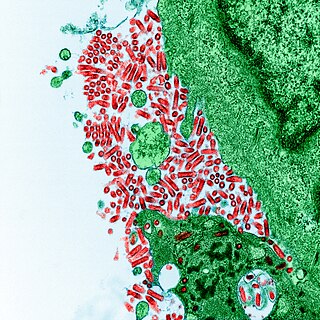

Sin Nombre virus (SNV) is the most common cause of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) in North America. Sin Nombre virus is transmitted mainly by the eastern deer mouse. In its natural reservoir, SNV causes an asymptomatic, persistent infection and is spread through excretions, fighting, and grooming. Humans can become infected by inhaling aerosols that contain rodent saliva, urine, or feces, as well as through bites and scratches. In humans, infection leads to HPS, an illness characterized by an early phase of mild and moderate symptoms such as fever, headache, and fatigue, followed by sudden respiratory failure. The case fatality rate from infection is high, at 30–50%.

Lyssavirus is a genus of RNA viruses in the family Rhabdoviridae, order Mononegavirales. Mammals, including humans, can serve as natural hosts. The genus Lyssavirus includes the causative agent of rabies.

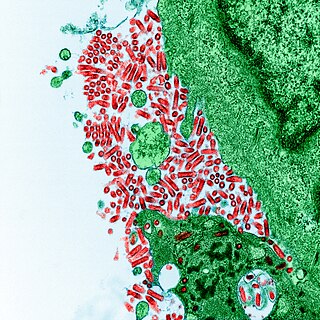

Rabies virus, scientific name Rabies lyssavirus, is a neurotropic virus that causes rabies in animals, including humans. It can cause violence, hydrophobia, and fever. Rabies transmission can also occur through the saliva of animals and less commonly through contact with human saliva. Rabies lyssavirus, like many rhabdoviruses, has an extremely wide host range. In the wild it has been found infecting many mammalian species, while in the laboratory it has been found that birds can be infected, as well as cell cultures from mammals, birds, reptiles and insects. Rabies is reported in more than 150 countries and on all continents except Antarctica. The main burden of disease is reported in Asia and Africa, but some cases have been reported also in Europe in the past 10 years, especially in returning travellers.

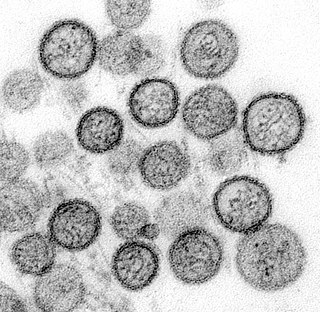

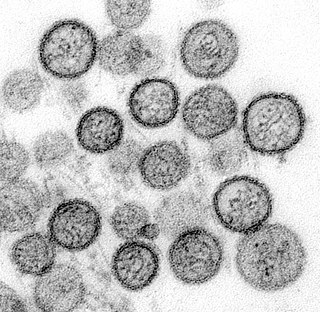

Lassa mammarenavirus (LASV) is an arenavirus that causes Lassa hemorrhagic fever, a type of viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF), in humans and other primates. Lassa mammarenavirus is an emerging virus and a select agent, requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment. It is endemic in West African countries, especially Sierra Leone, the Republic of Guinea, Nigeria, and Liberia, where the annual incidence of infection is between 300,000 and 500,000 cases, resulting in 5,000 deaths per year.

Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), originally named Pteropid lyssavirus (PLV), is a enzootic virus closely related to the rabies virus. It was first identified in a 5-month-old juvenile black flying fox collected near Ballina in northern New South Wales, Australia, in January 1995 during a national surveillance program for the recently identified Hendra virus. ABLV is the seventh member of the genus Lyssavirus and the only Lyssavirus member present in Australia. ABLV has been categorized to the Phylogroup I of the Lyssaviruses.

Mokola lyssavirus, commonly called Mokola virus (MOKV), is an RNA virus related to rabies virus that has been sporadically isolated from mammals across sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of isolates have come from domestic cats exhibiting symptoms characteristically associated to rabies virus infection.

Seoul virus (SEOV) is one of the main causes of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS). Seoul virus is transmitted by the brown rat and the black rat. In its natural reservoirs, SEOV causes an asymptomatic, persistent infection and is spread through excretions, fighting, and grooming. Humans can become infected by inhaling aerosols that contain rodent saliva, urine, or feces, as well as through bites and scratches. In humans, infection leads to HFRS, an illness characterized by general symptoms such as fever and headache, as well as the appearance of spots on the skin and renal symptoms such as kidney swelling, excess protein in urine, blood in urine, decreased urine production, and kidney failure. The case fatality rate from infection is 1–2%.

Snakehead rhabdovirus (SHRV) is a novirhabdovirus that affects warm water wild and pond-cultured fish of various species in Southeast Asia, including snakehead for which it is named.

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia because its victims panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abnormal sensations at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, violent movements, uncontrolled excitement, fear of water, an inability to move parts of the body, confusion, and loss of consciousness. Once symptoms appear, the result is virtually always death. The time period between contracting the disease and the start of symptoms is usually one to three months but can vary from less than one week to more than one year. The time depends on the distance the virus must travel along peripheral nerves to reach the central nervous system.

Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV) is the main cause of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) in southern Europe. In its natural reservoirs, DOBV causes a persistent, asymptomatic infection and is spread through excretions, fighting, and grooming. Humans can become infected by inhaling aerosols that contain rodent saliva, urine, or feces, as well as through bites and scratches. In humans, infection causes such as fever and headache, as well as the appearance of spots on the skin and renal symptoms such as kidney swelling, excess protein in urine, blood in urine, decreased urine production, and kidney failure. Acute respiratory distress syndrome occurs in about 10% of cases.

Cryptic rabies refers to infection from unrecognized exposure to rabies virus. It is often phylogenetically traced to bats. It is most often seen in the southern United States. Silver-haired bats and tricolored bats are the two most common bat species associated with this form of infection, though both species are known to have less contact with humans than other bat species such as the big brown bat. That species is common throughout the United States and often roosts in buildings and homes where human contact is more likely.

Hantaan virus (HTNV) is the main cause of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) in East Asia. Hantaan virus is transmitted by the striped field mouse In its natural reservoir, HTNV causes a persistent, asymptomatic infection and is spread through excretions, fighting, and grooming. Humans can become infected by inhaling aerosols that contain rodent saliva, urine, or feces, as well as through bites and scratches. In humans, infection causes such as fever and headache, as well as the appearance of spots on the skin, hepatitis, and renal symptoms such as kidney swelling, excess protein in urine, blood in urine, decreased urine production, and kidney failure. Rarely, HTNV infection affects the pituitary gland and can cause empty sella syndrome. The case fatality rate from infection is up to 6.3%.

The bat virome is the group of viruses associated with bats. Bats host a diverse array of viruses, including all seven types described by the Baltimore classification system: (I) double-stranded DNA viruses; (II) single-stranded DNA viruses; (III) double-stranded RNA viruses; (IV) positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses; (V) negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses; (VI) positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses that replicate through a DNA intermediate; and (VII) double-stranded DNA viruses that replicate through a single-stranded RNA intermediate. The greatest share of bat-associated viruses identified as of 2020 are of type IV, in the family Coronaviridae.

European bat 1 lyssavirus(EBLV-1) is one of three rabies virus-like agents of the genus Lyssavirus found in serotine bats in Spain. Strains of EBLV-1 have been identified as EBLV-1a and EBLV-1b. EBLV-1a was isolated from bats found in the Netherlands and Russia, while EBLV-1b was found in bats in France, the Netherlands and Iberia. E. isabellinus bats are the EBLV-1b reservoir in the Iberian Peninsula. Between 1977 and 2010, 959 bat rabies cases of EBLV-1 were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) Rabies Bulletin.

European bat 2 lyssavirus(EBLV-2) is one of three rabies-virus-like agents of the genus Lyssavirus found in Daubenton's bats in Great Britain. Human fatalities have occurred: the naturalist David McRae, who was bitten by a Daubenton's bat in Scotland, became infected with EBLV-2a and died in November 2002. It must now be assumed that the virus is present in bats in the UK. Testing of dead bats by MAFF/DEFRA over the last decade indicates that the overall incidence of infection is likely to be very low, although limited testing of live Daubenton's bats for antibodies suggests that exposure to EBLV-2 may be more widespread. Nevertheless, infected bat bites have caused human deaths so appropriate precautions against infection must be taken. The Department of Health’s recommendation is that people regularly handling bats should be vaccinated against rabies. Included in this category are all active bat workers and wardens, and those regularly taking in sick and injured bats. The Statutory Nature Conservation Organisations and the Bat Conservation Trust urge all those involved in bat work to ensure that they are fully vaccinated and that they receive regular boosters. Bats should not be handled by anyone who has not received these vaccinations. Even when fully vaccinated, people should avoid being bitten by wearing appropriate bite-proof gloves when handling bats. Any bat bite should be thoroughly cleansed with soap and water and advice should be sought from your doctor about the need for post-exposure treatment. Further information is available from the SNCOs, the Bat Conservation Trust or the Health Protection Agency (HPA) /Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health (SCIEH).

Bat mumps orthorubulavirus, formerly Bat mumps rubulavirus (BMV), is a member of genus Orthorubulavirus, family Paramyxoviridae, and order Mononegavirales. Paramyxoviridae viruses were first isolated from bats using heminested PCR with degenerate primers. This process was then followed by Sanger sequencing. A specific location of this virus is not known because it was isolated from bats worldwide. Although multiple paramyxoviridae viruses have been isolated worldwide, BMV specifically has not been isolated thus far. However, BMV was detected in African fruit bats, but no infectious form has been isolated to date. It is known that BMV is transmitted through saliva in the respiratory system of bats. While the virus was considered its own species for a few years, phylogenetic analysis has since shown that it is a member of Mumps orthorubulavirus.

Orthornavirae is a kingdom of viruses that have genomes made of ribonucleic acid (RNA), including genes which encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). The RdRp is used to transcribe the viral RNA genome into messenger RNA (mRNA) and to replicate the genome. Viruses in this kingdom share a number of characteristics which promote rapid evolution, including high rates of genetic mutation, recombination, and reassortment.