Work

Lewis and Scientific management

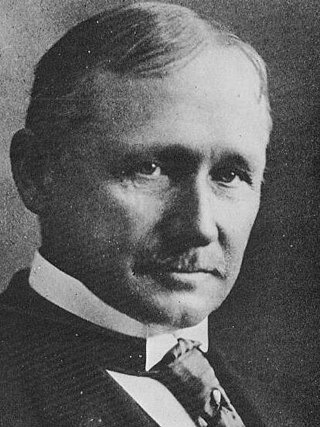

Lewis was a boyhood friend of Frederick Winslow Taylor, participated in the development of Taylor's work since the late 19th century, and became a promoter of scientific management in the first decennia of the 20th century. Taylor himself had developed his system of management at the Midvale Steel company. Afterwards he had introduced his system among others in the shops of the William Sellers and Company machine tool firm, sponsored by William Sellers himself, but this collapsed when Sellers retired. [11] As one of its directors Lewis had become acquainted with Taylor's system, but this didn't make a lasting impression. About their further interaction Merkle (1980) summarized:

- "...The two great showcases of Scientific Management, Tabor and Link-Belt, were not originally converted to Taylorism on the grounds of rational inquiry. Although after the Scientific Management fad had begun, the example of these two companies helped to convert other businesses to Taylorite organization, Taylorism was accepted at the Tabor Manufacturing Company as part of a debt, and at Link-Belt as part of the ideological conversion of one of Taylor's personal friends. Wilfred Lewis, a boyhood friend of Taylor, who had risen from draftsman at Sellers to become a mechanical engineer, had come to be one of the heads of the Tabor company. Shortly after 1900, Tabor started to lose money, and the process was accelerated by a series of strikes. With the new, higher wages, other companies were producing the same product at a lower cost, and the company went from selling stock to outright borrowing. Lewis went to his friends for money, among them Taylor. "Use my system," said Taylor, in effect, "or you shall have no money." In desperation, Lewis accepted, in spite of the fact that the genteel inhabitants of Philadelphia considered his friend a management crank. Straightaway, Barth, and then Taylor himself descended upon the Tabor plant, where they created the first showplace of Scientific Management..." [11]

Over the years Wilfred Lewis became strong believer and promoter of scientific management. About one of his latest stands, Kyle and Nyland (1993) summarized: [12]

- "In December 1927 the industrialist Wilfred Lewis delivered a paper to the Taylor Society in which he lauded the achievements of the scientific management movement. Lewis claimed the four key objectives of the movement had become the reduction of costs, the raising of wages, the encouragement of collaboration between employers and employees and the full employment of workers and machinery. The extent to which these objectives were being attained, he concluded, enabled the people of "America to look forward hopefully to the future" (Lewis 1927, 557)." [12]

About the response Kyle and Nyland (1993) summarized:

- "The response to Lewis' paper indicated that not all members of the Taylor Society shared his optimism. While he was praised by some commentators, his suggestion that there was wide acceptance amongst employers of the positive value of high wages was challenged. It was also observed that his belief the good times were "practically certain to continue .... is an assumption which may well be questioned" (Muste 1928, 47)" [12]