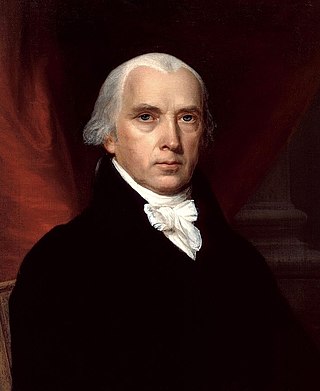

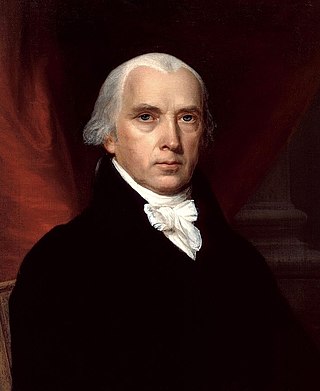

James Madison was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

Dolley Todd Madison was the wife of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. She was noted for holding Washington social functions in which she invited members of both political parties, essentially spearheading the concept of bipartisan cooperation. Previously, founders such as Thomas Jefferson would only meet with members of one party at a time, and politics could often be a violent affair resulting in physical altercations and even duels. Madison helped to create the idea that members of each party could amicably socialize, network, and negotiate with each other without violence. By innovating political institutions as the wife of James Madison, Dolley Madison did much to define the role of the President's spouse, known only much later by the title First Lady—a function she had sometimes performed earlier for the widowed Thomas Jefferson.

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States refers to the institution of slavery that existed in the European colonies in North America which eventually became part of the United States of America. Slavery developed due to a combination of factors, primarily the labor demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies, which had resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by European colonists during the era.

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, or imposed involuntarily as a judicial punishment. The practice has been compared to the similar institution of slavery, although there are differences.

Gabriel's Rebellion was a planned slave rebellion in the Richmond, Virginia, area in the summer of 1800. Information regarding the revolt was leaked before its execution, and Gabriel, an enslaved blacksmith who planned the event, and twenty-five of his followers were hanged.

Edward Coles was an American planter and politician, elected as the second Governor of Illinois. From an old Virginia family, Coles as a young man was a neighbor and associate of presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, as well as, secretary to President James Madison from 1810 to 1815.

James Madison's Montpelier, located in Orange County, Virginia, was the plantation house of the Madison family, including Founding Father and fourth president of the United States James Madison and his wife, Dolley. The 2,650-acre (1,070 ha) property is open seven days a week.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of slave mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property; analogous legislation existed in other civilizations including Medieval Egypt in Africa and Korea in Asia.

Madison Hemings was the son of Sally Hemings and, most likely, Thomas Jefferson. He was the third of Sally Hemings’ four children to survive to adulthood. Born into slavery, according to partus sequitur ventrem, Hemings grew up on Jefferson's Monticello plantation, where his mother was also enslaved. After some light duties as a young boy, Hemings became a carpenter and fine woodwork apprentice at around age 14 and worked in the joiner's shop until he was about 21. He learned to play the violin and was able to earn money by growing cabbages. Jefferson died in 1826, after which Sally Hemings was "given her time" by Jefferson's surviving daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph.

The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, were a series of laws enacted by the Colony of Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1705 regulating the interactions between slaves and citizens of the crown colony of Virginia. The enactment of the Slave Codes is considered to be the consolidation of slavery in Virginia, and served as the foundation of Virginia's slave legislation. All servants from non-Christian lands became slaves. There were forty one parts of this code each defining a different part and law surrounding the slavery in Virginia. These codes overruled the other codes in the past and any other subject covered by this act are canceled.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Ambrose Madison was an American planter and politician in the Piedmont of Virginia Colony. He married Frances Taylor in 1721, daughter of James Taylor, a member of the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition across the Blue Ridge Mountains from the Tidewater. Through her father, Madison and his brother-in-law Thomas Chew were aided in acquiring 4,675 acres in 1723, in what became Orange County. There he developed his tobacco plantation known as Mount Pleasant The Madisons were parents of James Madison Sr. and paternal grandparents of President James Madison.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

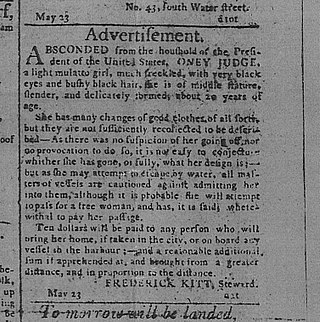

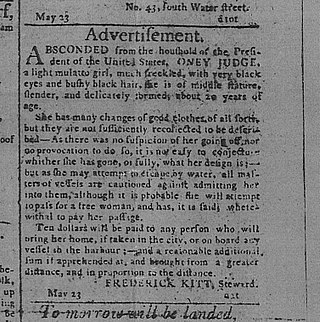

Paul Jennings was an American abolitionist and writer. Enslaved as a young man by President James Madison during and after his White House years, Jennings published, in 1865, the first White House memoir. His book was A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison, described as "a singular document in the history of slavery and the early American republic."

An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the Fifth Pennsylvania General Assembly on 1 March 1780, prescribed an end for slavery in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States. It was the first slavery abolition act in the course of human history to be adopted by an elected body.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

Indentured servitude in British America was the prominent system of labor in the British American colonies until it was eventually supplanted by slavery. During its time, the system was so prominent that more than half of all immigrants to British colonies south of New England were white servants, and that nearly half of total white immigration to the Thirteen Colonies came under indenture. By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial labor force was composed of indentured servants.

Throughout his life, James Madison's views on slavery and his ownership of slaves were complex. James Madison, who was a Founding Father of the United States and its 4th president, grew up on a plantation that made use of slave labor. He viewed slavery as a necessary part of the Southern economy, though he was troubled by the instability of a society that depended on a large slave population. Madison did not free his slaves during his lifetime or in his will.

Nelly Madison was a prominent Virginia socialite and planter who was the mother of James Madison Jr., the 4th president of the United States and Lieutenant General William Taylor Madison. She has been described as one of the strongest female influences in the life of James Madison Jr., and has been credited for her efforts to preserve the Montpelier estate.