Biology – The natural science that studies life. Areas of focus include structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, distribution, and taxonomy.

Invertebrates is an umbrella term describing animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column, which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordate subphylum Vertebrata, i.e. vertebrates. Well-known phyla of invertebrates include arthropods, mollusks, annelids, echinoderms, flatworms, cnidarians and sponges.

Zoology is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the structure, embryology, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct, and how they interact with their ecosystems. Zoology is one of the primary branches of biology. The term is derived from Ancient Greek ζῷον, zōion ('animal'), and λόγος, logos.

Arachnida is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.

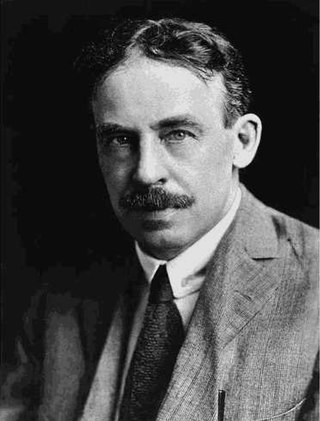

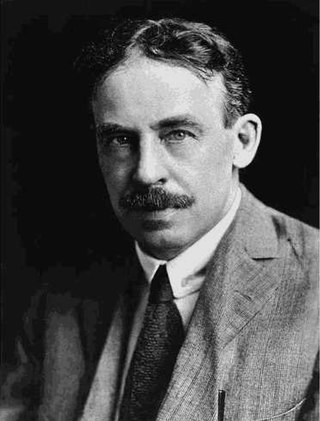

William Morton Wheeler was an American entomologist, myrmecologist and professor at Harvard University.

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Eugenics Society.

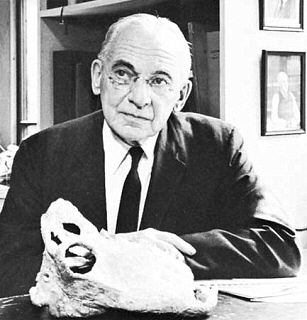

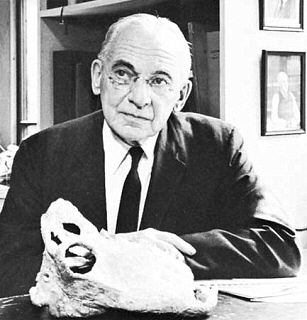

Alfred Sherwood Romer was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Ostracoderms are the armored jawless fish of the Paleozoic Era. The term does not often appear in classifications today because it is paraphyletic and thus does not correspond to one evolutionary lineage. However, the term is still used as an informal way of loosely grouping together the armored jawless fishes.

Heinz Christian Pander, also Christian Heinrich Pander, was a Russian Empire ethnic Baltic German biologist and embryologist.

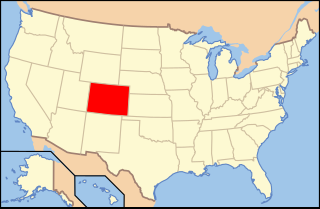

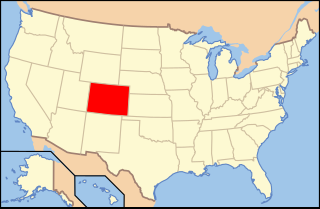

Ralph Vary Chamberlin was an American biologist, ethnographer, and historian from Salt Lake City, Utah. He was a faculty member of the University of Utah for over 25 years, where he helped establish the School of Medicine and served as its first dean, and later became head of the zoology department. He also taught at Brigham Young University and the University of Pennsylvania, and worked for over a decade at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, where he described species from around the world.

A body plan, Bauplan, or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book Embryos and Ancestors. He was director of the Natural History Museum, London, president of the Linnean Society of London, and a winner of the Royal Society's Darwin Medal for his studies on evolution.

Dartmuthia is an extinct genus of primitive jawless fish that lived in the Silurian period. Fossils of Dartmuthia have been found in Himmiste Quarry, on the island of Saaremaa in Estonia. It was first described by William Patten.

David Burton Wake was an American herpetologist. He was professor of integrative biology and Director and curator of herpetology of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley. Wake is known for his work on the biology and evolution of salamanders as well as general issues of vertebrate evolutionary biology. He has served as president of the Society for the Study of Evolution, the American Society of Naturalists, and American Society of Zoologists. He was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Linnean Society of London, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and in 1998 was elected into the National Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the 2006 Leidy Award from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Bruce R. Erickson was an American paleontologist and the former Fitzpatrick Chair of Paleontology at the Science Museum of Minnesota. During the course of his lifetime and his 55 years as a paleontologist, he has "collected about a million specimens" and discovered fifteen new types of plants and ancient animal species. His collection includes "a triceratops skeleton" that he discovered in 1961 at the Hell Creek Formation that is considered to be "one of the rarest in the world". His research has focused almost entirely on the Paleocene era in history.

Oscar Werner Tiegs FRS FAA was an Australian zoologist whose career spanned the first half of the 20th century.

The Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "for meritorious work in zoology or paleontology study published in a three- to five-year period." Named after Daniel Giraud Elliot, it was first awarded in 1917.

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

The evolution of fish began about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. It was during this time that the early chordates developed the skull and the vertebral column, leading to the first craniates and vertebrates. The first fish lineages belong to the Agnatha, or jawless fish. Early examples include Haikouichthys. During the late Cambrian, eel-like jawless fish called the conodonts, and small mostly armoured fish known as ostracoderms, first appeared. Most jawless fish are now extinct; but the extant lampreys may approximate ancient pre-jawed fish. Lampreys belong to the Cyclostomata, which includes the extant hagfish, and this group may have split early on from other agnathans.

Edward Phelps Allis (1851–1947) was a leading comparative anatomist and evolutionary morphologist in the early twentieth century. Some of the illustrations in his publications were considered the best of lower vertebrates until at least the 1980s.