A chordate is a deuterostomic bilaterial animal belonging to the phylum Chordata. All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five distinctive physical characteristics (synapomorphies) that distinguish them from other taxa. These five synapomorphies are a notochord, a hollow dorsal nerve cord, an endostyle or thyroid, pharyngeal slits, and a post-anal tail.

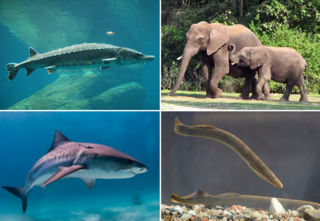

Vertebrates are deuterostomal animals with bony or cartilaginous axial endoskeleton — known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone — around and along the spinal cord, including all fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. The vertebrates consist of all the taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata and represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with currently about 69,963 species described.

Agnatha is a paraphyletic infraphylum of non-gnathostome vertebrates, or jawless fish, in the phylum Chordata, subphylum Vertebrata, consisting of both living (cyclostomes) and extinct. Among recent animals, cyclostomes are sister to all vertebrates with jaws, known as gnathostomes.

Gnathostomata are the jawed vertebrates. Gnathostome diversity comprises roughly 60,000 species, which accounts for 99% of all living vertebrates, including humans. Most gnathostomes have retained ancestral traits like true teeth, a stomach, and paired appendages. Other traits are elastin, a horizontal semicircular canal of the inner ear, myelin sheaths of neurons, and an adaptive immune system which has discrete lymphoid organs, and uses V(D)J recombination to create antigen recognition sites, rather than using genetic recombination in the variable lymphocyte receptor gene.

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term jaws is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serving to open and close it and is part of the body plan of humans and most animals.

A craniate is a member of the Craniata, a proposed clade of chordate animals with a skull of hard bone or cartilage. Living representatives are the Myxini (hagfishes), Hyperoartia, and the much more numerous Gnathostomata. Formerly distinct from vertebrates by excluding hagfish, molecular and anatomical research in the 21st century has led to the reinclusion of hagfish as vertebrates, making living craniates synonymous with living vertebrates.

Acanthodii or acanthodians is an extinct class of gnathostomes. They are currently considered to represent a paraphyletic grade of various fish lineages basal to extant Chondrichthyes, which includes living sharks, rays, and chimaeras. Acanthodians possess a mosaic of features shared with both osteichthyans and chondrichthyans. In general body shape, they were similar to modern sharks, but their epidermis was covered with tiny rhomboid platelets like the scales of holosteians.

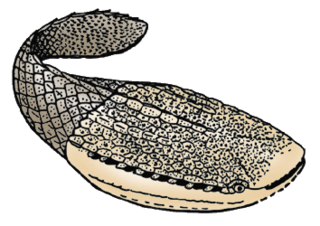

Placoderms are vertebrate animals of the class Placodermi, an extinct group of prehistoric fish known from Paleozoic fossils during the Silurian and the Devonian periods. While their endoskeletons are mainly cartilaginous, their head and thorax were covered by articulated armoured plates, and the rest of the body was scaled or naked depending on the species.

Pharyngeal slits are filter-feeding organs found among deuterostomes. Pharyngeal slits are repeated openings that appear along the pharynx caudal to the mouth. With this position, they allow for the movement of water in the mouth and out the pharyngeal slits. It is postulated that this is how pharyngeal slits first assisted in filter-feeding, and later, with the addition of gills along their walls, aided in respiration of aquatic chordates. These repeated segments are controlled by similar developmental mechanisms. Some hemichordate species can have as many as 200 gill slits. Pharyngeal clefts resembling gill slits are transiently present during the embryonic stages of tetrapod development. The presence of pharyngeal arches and clefts in the neck of the developing human embryo famously led Ernst Haeckel to postulate that "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"; this hypothesis, while false, contains elements of truth, as explored by Stephen Jay Gould in Ontogeny and Phylogeny. However, it is now accepted that it is the vertebrate pharyngeal pouches and not the neck slits that are homologous to the pharyngeal slits of invertebrate chordates. Pharyngeal arches, pouches, and clefts are, at some stage of life, found in all chordates. One theory of their origin is the fusion of nephridia which opened both on the outside and the gut, creating openings between the gut and the environment.

Thelodonti is a class of extinct Palaeozoic jawless fishes with distinctive scales instead of large plates of armor.

Cyclostomi, often referred to as Cyclostomata, is a group of vertebrates that comprises the living jawless fishes: the lampreys and hagfishes. Both groups have jawless mouths with horny epidermal structures that function as teeth called ceratodontes, and branchial arches that are internally positioned instead of external as in the related jawed fishes. The name Cyclostomi means "round mouths". It was named by Joan Crockford-Beattie.

Astraspida, or astraspids, are a small group of extinct armored jawless vertebrates, which lived in the Late Ordovician in North America. They are placed among the Pteraspidomorphi because of the large dorsal and ventral shield of their head armor. They are represented by a single genus, Astraspis, including possibly two species, A. desiderata and A. splendens but their remains are fairly abundant in Ordovician sandstones of the USA and Canada (Quebec). The head armor of Astraspis is rather massive, with a series of ten gill openings lining the margin of the dorsal shield, and laterally placed eyes. The dorsal shield is ribbed by strong longitudinal crests, and the tail is covered with large, diamond-shaped scales. They are often grouped together with the Arandaspidida.

Branchial arches or gill arches are a series of paired bony/cartilaginous "loops" behind the throat of fish, which support the fish gills. As chordates, all vertebrate embryos develop pharyngeal arches, though the eventual fate of these arches varies between taxa. In all jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes), the first arch pair develops into the jaw, the second gill arches develop into the hyomandibular complex, and the remaining posterior arches support the gills. In tetrapods, a mostly terrestrial clade evolved from lobe-finned fish, many pharyngeal arch elements are lost, including the gill arches. In amphibians and reptiles, only the oral jaws and a hyoid apparatus remains, and in mammals and birds the hyoid is simplified further to support the tongue and floor of the mouth. In mammals, the first and second branchial arches also give rise to the auditory ossicles.

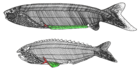

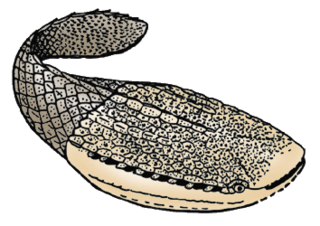

Metaspriggina is a genus of chordate initially known from two specimens in the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale and 44 specimens found in 2012 at the Marble Canyon bed in Kootenay National Park.

Mark Andrew Purnell is a British palaeontologist, Professor of Palaeobiology at the University of Leicester.

Most bony fishes have two sets of jaws made mainly of bone. The primary oral jaws open and close the mouth, and a second set of pharyngeal jaws are positioned at the back of the throat. The oral jaws are used to capture and manipulate prey by biting and crushing. The pharyngeal jaws, so-called because they are positioned within the pharynx, are used to further process the food and move it from the mouth to the stomach.

The evolution of fish began about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. It was during this time that the early chordates developed the skull and the vertebral column, leading to the first craniates and vertebrates. The first fish lineages belong to the Agnatha, or jawless fish. Early examples include Haikouichthys. During the late Cambrian, eel-like jawless fish called the conodonts, and small mostly armoured fish known as ostracoderms, first appeared. Most jawless fish are now extinct; but the extant lampreys may approximate ancient pre-jawed fish. Lampreys belong to the Cyclostomata, which includes the extant hagfish, and this group may have split early on from other agnathans.

Entelognathus primordialis is an early placoderm from the late Silurian of Qujing, Yunnan, 419 million years ago.

Panderodus Is an extinct genus of jawless fish belonging to the order Conodonta. This genus had a long temporal range, surviving from the middle Ordovician to late Devonian. In 2021, extremely rare body fossils of Panderodus from the Waukesha Biota were described, and it revealed that Panderodus had a more thick body compared to the more slender bodies of more advanced conodonts. It also revealed that this conodont was a macrophagous predator, meaning it went after large prey.

The evolution of fishes took place over a timeline which spans the Cambrian to the Cenozoic, including during that time in particular the Devonian, which has been dubbed the "age of fishes" for the many changes during that period.