Life

Royal courtier and chaplain

Little is known about William. He or at least his family was presumably from Chartres. He was probably of "lower class non-noble origins". He may be the William of Chartres described as a cleric and scholar at Vercelli who stood as surety for some Frenchmen studying in Italy in 1231. He was employed at the royal court by 1248. At the time, he was a secular cleric. He may have been brought to the king's attention by Robert of Douai, the queen's physician.

William was a part of Louis's inner circle during the Seventh Crusade. He went into captivity along with the king in 1250. In March 1251, Louis provided William's two sisters and their eldest sons with an income from rents. He returned to France with Louis after a period in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1254. That year William became a canon of Saint-Quentin. He is referred to in documents of this time as "Lord William" and was attached to the royal chapel. In 1254–1255, acting as a royal agent, he purchased properties on the left bank of the Seine for the Sorbonne. One of the properties was a house of Robert of Douai. In 1255–1256, he was rewarded with a horse and a cape.

By February 1259, Louis had appointed William treasurer of Saint-Frambourg de Senlis. A document of 1261 calls him a priest. On 6 July 1262, William signed as a witness the treaty of friendship between Louis IX and James I of Aragon on the occasion of the marriage of Louis's son, Philip, and James's daughter, Isabella.

Dominican crusader

According to his own account, William held the office of treasurer for five and a half years. He is last recorded in that capacity in December 1263 and must have entered the Dominican Order the following year. [7] He resided in the Parisian convent of Saint-Jacques on the left bank. In 1269–1270, he took part in the preparations of the Eighth Crusade. He joined the expedition as a royal confessor, took possession of the royal seal after the death of the archdeacon of Paris on 20 August and was at Louis's side when the king died.

Following Louis's death, William was sent back to France by Louis's successor, Philip III, along with two other friars, Geoffrey of Beaulieu and John of Mons. The three carried four letters from Philip dated 12 September 1270 informing the ecclesiastical and lay magnates of the kingdom of Louis's death and confirming Matthew of Vendôme and Simon of Nesle in the regency. They travelled by way of Sicily and Italy, crossing the Alps and arriving at Paris by early October. [10] William remained in Paris for the next three years, working as a parish priest.

Death

William began work on his biography of Louis IX after January 1273, after the death of Geoffrey of Beaulieu, who had written his own biography of Louis, and seemingly while Pope Gregory X was still alive. He was most likely actively writing in 1274–1275. The last record of William is an undated letter he wrote to his brother-in-law, Gilles de la Chaussée, probably in 1277. In it he informs Gilles that he has secured letters from Philip III asking Matthew of Vendôme to receive Gilles's son Matthew into the Abbey of Saint-Denis. William was probably dead by 1282, since he did not testify at the inquiry for Louis's canonization. [13]

Works

Three sermon's preached by William are preserved. These were preached on 2 February 1273 at Saint-Leufroy [ fr ] and on 12 and 19 February at La Madeleine. They are found in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), MS lat. 16481. Pierre Daunou considered them poor sermons and not worth publishing. They are still unedited. In the Archives Nationales, carton J 1030, document no. 59 is the autograph of William's letter to his brother-in-law.

On the Life and Deeds of Louis, King of the Franks of Famous Memory, and on the Miracles That Declare His Sanctity, William's Latin biography of Louis IX, is preserved alongside Geoffrey of Beaulieu's in a single manuscript, BnF, MS lat. 13778, at folios 41v–64v. William's work was never as widely cited as Geoffrey's. It is also shorter and lacks chapter headings. Both works are hagiography, intended to demonstrate Louis's sainthood. Geoffrey's was the first and William's the second biography of Louis IX and both texts have often been printed together.

William wrote his work as a companion piece of Geoffrey's. He enumerated four areas where he intended to complete Geoffrey's biography: "the good days of [Louis's] rule", his imprisonment, his death and the miracles that had occurred at his tomb and through his intercession. It is in the first of these areas that William's biography is most interesting to modern historians. [19] In recounting the justness of Louis's administration—e.g., his suppression of private warfare and trial by battle—On the Life and Deeds reads at times like a mirror of princes. It is the only eyewitness account of Louis's captivity.

Like standard hagiographies of the time, On the Life and Deeds consists of two basic parts: the life (vita) proper and the miracles (miracula). Paragraphs 1–3 of contain metaphors comparing Louis to the sun among stars and the Biblical king Josiah. He also describes Geoffrey's biography and his own purpose and method. Paragraph 4 is a description of Louis's institution of an annual procession of the relic of the crown of thorns at Sainte-Chapelle. Paragraph 5 describes how the king kept the Sabbath (Sunday). Most of the remainder of the work keeps to the themes neglected by Geoffrey. Paragraphs 6–10 cover the Seventh Crusade and Louis's captivity in Egypt; Louis's government of France is covered in paragraphs 12–27; his illness and death in 37–42; and seventeen posthumous miracles in 43–60 (with an introductory paragraph and one paragraph per miracle). William breaks with his declared themes at paragraph 11, where he tells how Louis had predicted that he would become a Dominican, and paragraphs 28–36, which describe Louis's various acts of religious devotion: footwashing, fasting, almsgiving, caring for lepers, building hospitals for the poor and endowing friaries and churches.

William's seventeen miracles form the earliest collection of miracles attributed to Louis. All took place between October 1270 and August 1271. [23] William presents all the miracles as properly authenticated, usually dated, and apparently collected many of the accounts himself. He may have had access to the list of miracles kept at Saint-Denis by Thomas Hauxton on Philip III's orders. All seventeen recorded by William were later included in the Beatus Ludovicus , which assured them a wider audience than On the Life and Deeds received.

Alphonse was the Count of Poitou from 1225 and Count of Toulouse from 1249. As count of Toulouse, he also governed the Marquisate of Provence.

Louis IX, also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis VIII, he was crowned in Reims at the age of 12. His mother, Blanche of Castile, effectively ruled the kingdom as regent until he came of age and continued to serve as his trusted adviser until her death. During his formative years, Blanche successfully confronted rebellious vassals and championed the Capetian cause in the Albigensian Crusade, which had been ongoing for the past two decades.

Year 1270 (MCCLXX) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar, the 1270th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 270th year of the 2nd millennium, the 70th year of the 13th century, and the 1st year of the 1270s decade.

Philip III, called the Bold, was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned to France and was anointed king at Reims in 1271.

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any significant fighting as Louis died of dysentery shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia. The Treaty of Tunis was negotiated between the Crusaders and the Hafsids. No changes in territory occurred, though there were commercial and some political rights granted to the Christians. The Crusaders withdrew back to Europe soon after.

Jean de Joinville was one of the great chroniclers of medieval France. He is most famous for writing the Life of Saint Louis, a biography of Louis IX of France that chronicled the Seventh Crusade.

The Seventh Crusade (1248–1254) was the first of the two Crusades led by Louis IX of France. Also known as the Crusade of Louis IX to the Holy Land, it aimed to reclaim the Holy Land by attacking Egypt, the main seat of Muslim power in the Near East. The Crusade was conducted in response to setbacks in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, beginning with the loss of the Holy City in 1244, and was preached by Innocent IV in conjunction with a crusade against emperor Frederick II, Baltic rebellions and Mongol incursions. After initial success, the crusade ended in defeat, with most of the army – including the king – captured by the Muslims.

Margaret, often called Margaret of Constantinople, ruled as Countess of Flanders during 1244–1278 and Countess of Hainaut during 1244–1253 and 1257–1280. She was the younger daughter of Baldwin IX, Count of Flanders and Hainaut, and Marie of Champagne.

Amaury de Montfort, Lord of Montfort-l'Amaury, was the son of Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl of Leicester and Alix de Montmorency, and the older brother of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester. Amaury inherited his father's French properties while his brother Simon inherited the English title of Earl of Leicester.

William I of Champlitte (1160s-1209) was a French knight who joined the Fourth Crusade and became the first prince of Achaea (1205–1209).

The Battle of Fariskur was the last major battle of the Seventh Crusade. The battle was fought on 6 April 1250, between the Crusaders led by King Louis IX of France and Egyptian forces led by Turanshah of the Ayyubid dynasty.

The Saintonge War was a feudal dynastic conflict that occurred between 1242 and 1243. It opposed Capetian forces supportive of King Louis IX's brother Alphonse, Count of Poitiers and those of Hugh X of Lusignan, Raymond VII of Toulouse and Henry III of England. The latter hoped to regain the Angevin possessions lost during his father's reign. Saintonge is the region around Saintes in the centre-west of France and is the place where most of fighting occurred.

Geoffrey of Beaulieu, from Évreux in Normandy, was a French friar and biographer.

Peter I of Alençon was the son of Louis IX of France and Margaret of Provence.

Louis of France was the eldest son of King Louis IX of France and his wife Margaret of Provence. As heir apparent to the throne, he served as regent for a brief period.

Robert of Nantes was the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem from 1240 to 1254.

Matthew of Vendôme was the abbot of Saint-Denis from 1258 until 1286 and one of the regents of France from 1270 until 1271.

Saint Louis is a 1996 biography of Louis IX of France by historian Jacques Le Goff. The book received positive reviews for its historical detail, and was awarded the 1996 Grand prix Gobert by the French Academy. It was also a best-seller.

The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages is a 2010 book by historian M. Cecilia Gaposchkin. Gaposchkin draws on hagiographical, visual, and narrative material, as well as little-used liturgical sources and sermons, to discuss the process by which Louis was canonized and made a saint in the eyes of a large public. The book was praised by other scholars.

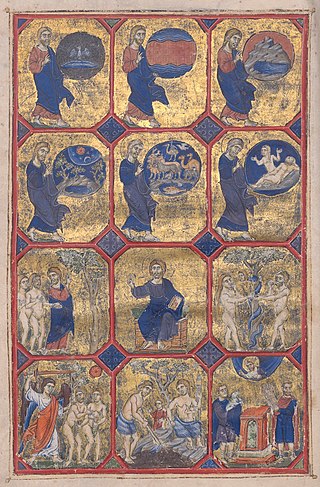

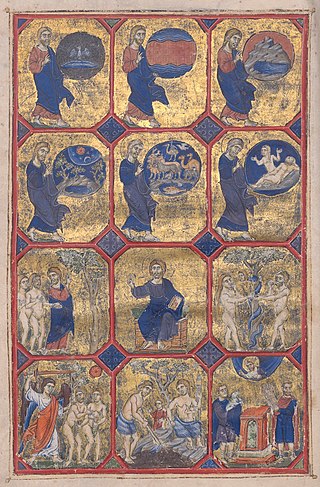

The Acre Bible is a partial Old French version of the Old Testament, containing both new and revised translations of 15 canonical and 4 deuterocanonical books, plus a prologue and glosses. The books are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, Judith, Esther, Job, Tobit, Proverbs, 1 and 2 Maccabees and Ruth. It is an early and somewhat rough vernacular translation. Its version of Job is the earliest vernacular translation in Western Europe.