A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and enable mobility. Bones come in a variety of shapes and sizes and have complex internal and external structures. They are lightweight yet strong and hard and serve multiple functions.

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tension.

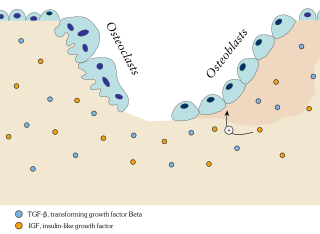

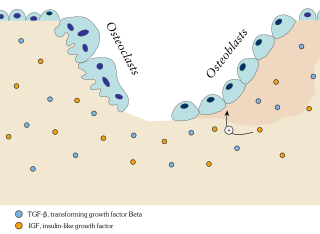

Osteoblasts are cells with a single nucleus that synthesize bone. However, in the process of bone formation, osteoblasts function in groups of connected cells. Individual cells cannot make bone. A group of organized osteoblasts together with the bone made by a unit of cells is usually called the osteon.

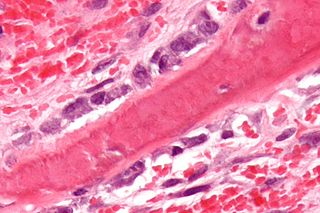

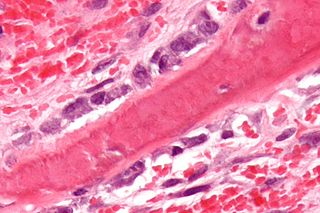

A trabecula is a small, often microscopic, tissue element in the form of a small beam, strut or rod that supports or anchors a framework of parts within a body or organ. A trabecula generally has a mechanical function, and is usually composed of dense collagenous tissue. It can be composed of other material such as muscle and bone. In the heart, muscles form trabeculae carneae and septomarginal trabeculae. Cancellous bone is formed from groupings of trabeculated bone tissue.

An osteocyte, an oblate shaped type of bone cell with dendritic processes, is the most commonly found cell in mature bone. It can live as long as the organism itself. The adult human body has about 42 billion of them. Osteocytes do not divide and have an average half life of 25 years. They are derived from osteoprogenitor cells, some of which differentiate into active osteoblasts. Osteoblasts/osteocytes develop in mesenchyme.

The periodontal ligament, commonly abbreviated as the PDL, is a group of specialized connective tissue fibers that essentially attach a tooth to the alveolar bone within which it sits. It inserts into root cementum on one side and onto alveolar bone on the other.

In cellular biology, mechanotransduction is any of various mechanisms by which cells convert mechanical stimulus into electrochemical activity. This form of sensory transduction is responsible for a number of senses and physiological processes in the body, including proprioception, touch, balance, and hearing. The basic mechanism of mechanotransduction involves converting mechanical signals into electrical or chemical signals.

Bone resorption is resorption of bone tissue, that is, the process by which osteoclasts break down the tissue in bones and release the minerals, resulting in a transfer of calcium from bone tissue to the blood.

Sclerostin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SOST gene. It is a secreted glycoprotein with a C-terminal cysteine knot-like (CTCK) domain and sequence similarity to the DAN family of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonists. Sclerostin is produced primarily by the osteocyte but is also expressed in other tissues, and has anti-anabolic effects on bone formation.

Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), also known as tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 11 (TNFSF11), TNF-related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE), osteoprotegerin ligand (OPGL), and osteoclast differentiation factor (ODF), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TNFSF11 gene.

Davis's law is used in anatomy and physiology to describe how soft tissue models along imposed demands. It is similar to Wolff's law, which applies to osseous tissue. It is a physiological principle stating that soft tissue heal according to the manner in which they are mechanically stressed.

The Mechanostat is a term describing the way in which mechanical loading influences bone structure by changing the mass and architecture to provide a structure that resists habitual loads with an economical amount of material. As changes in the skeleton are accomplished by the processes of formation and resorption, the mechanostat models the effect of influences on the skeleton by those processes, through their effector cells, osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. The term was invented by Harold Frost: an orthopaedic surgeon and researcher described extensively in articles referring to Frost and Webster Jee's Utah Paradigm of Skeletal Physiology in the 1960s. The Mechanostat is often defined as a practical description of Wolff's law described by Julius Wolff (1836–1902), but this is not completely accurate. Wolff wrote his treatises on bone after images of bone sections were described by Culmann and von Meyer, who suggested that the arrangement of the struts (trabeculae) at the ends of the bones were aligned with the stresses experienced by the bone. It has since been established that the static methods used for those calculations of lines of stress were inappropriate for work on what were, in effect, curved beams, a finding described by Lance Lanyon, a leading researcher in the area as "a triumph of a good idea over mathematics." While Wolff pulled together the work of Culmann and von Meyer, it was the French scientist Roux, who first used the term "functional adaptation" to describe the way that the skeleton optimized itself for its function, though Wolff is credited by many for that.

In osteology, bone remodeling or bone metabolism is a lifelong process where mature bone tissue is removed from the skeleton and new bone tissue is formed. These processes also control the reshaping or replacement of bone following injuries like fractures but also micro-damage, which occurs during normal activity. Remodeling responds also to functional demands of the mechanical loading.

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the LRP5 gene. LRP5 is a key component of the LRP5/LRP6/Frizzled co-receptor group that is involved in canonical Wnt pathway. Mutations in LRP5 can lead to considerable changes in bone mass. A loss-of-function mutation causes osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome with a decrease in bone mass, while a gain-of-function mutation causes drastic increases in bone mass.

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the LRP6 gene. LRP6 is a key component of the LRP5/LRP6/Frizzled co-receptor group that is involved in canonical Wnt pathway.

Stress shielding is the reduction in bone density (osteopenia) as a result of removal of typical stress from the bone by an implant. This is because by Wolff's law, bone in a healthy person or animal remodels in response to the loads it is placed under.It is possible to mention the elastic modulus of Magnesium compared to Titanium, stainless steel, iron, or zinc, which makes it further analogous to the natural bone of the body and prevents stress shielding phenomenaPorous implantation is one typical alleviation method.

Mechanotherapy is a type of medical therapeutics in which treatment is given by manual or mechanical means. It was defined in 1890 as “the employment of mechanical means for the cure of disease”. Mechanotherapy employs mechanotransduction in order to stimulate tissue repair and remodelling.

Mechanobiology is an emerging field of science at the interface of biology, engineering, chemistry and physics. It focuses on how physical forces and changes in the mechanical properties of cells and tissues contribute to development, cell differentiation, physiology, and disease. Mechanical forces are experienced and may be interpreted to give biological responses in cells. The movement of joints, compressive loads on the cartilage and bone during exercise, and shear pressure on the blood vessel during blood circulation are all examples of mechanical forces in human tissues. A major challenge in the field is understanding mechanotransduction—the molecular mechanisms by which cells sense and respond to mechanical signals. While medicine has typically looked for the genetic and biochemical basis of disease, advances in mechanobiology suggest that changes in cell mechanics, extracellular matrix structure, or mechanotransduction may contribute to the development of many diseases, including atherosclerosis, fibrosis, asthma, osteoporosis, heart failure, and cancer. There is also a strong mechanical basis for many generalized medical disabilities, such as lower back pain, foot and postural injury, deformity, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Vascular remodelling is a process which occurs when an immature heart begins contracting, pushing fluid through the early vasculature. The process typically begins at day 22, and continues to the tenth week of human embryogenesis. This first passage of fluid initiates a signal cascade and cell movement based on physical cues including shear stress and circumferential stress, which is necessary for the remodelling of the vascular network, arterial-venous identity, angiogenesis, and the regulation of genes through mechanotransduction. This embryonic process is necessary for the future stability of the mature vascular network.

Craniofacial regeneration refers to the biological process by which the skull and face regrow to heal an injury. This page covers birth defects and injuries related to the craniofacial region, the mechanisms behind the regeneration, the medical application of these processes, and the scientific research conducted on this specific regeneration. This regeneration is not to be confused with tooth regeneration. Craniofacial regrowth is broadly related to the mechanisms of general bone healing.