Sports journalism is a form of writing that reports on matters pertaining to sporting topics and competitions. Sports journalism has its roots in coverage of horse racing and boxing in the early 1800s, mainly targeted towards elites, and into the 1900s transitioned into an integral part of the news business with newspapers having dedicated sports sections. The increased popularity of sports amongst the middle and lower class led to the more coverage of sports content in publications. The appetite for sports resulted in sports-only media such as Sports Illustrated and ESPN. There are many different forms of sports journalism, ranging from play-by-play and game recaps to analysis and investigative journalism on important developments in the sport. Technology and the internet age has massively changed the sports journalism space as it is struggling with the same problems that the broader category of print journalism is struggling with, mainly not being able to cover costs due to falling subscriptions. New forms of internet blogging and tweeting in the current millennium have pushed the boundaries of sports journalism.

The Miami Herald is an American daily newspaper owned by The McClatchy Company and headquartered in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Founded in 1903, it is the fifth-largest newspaper in Florida, serving Miami-Dade, Broward, and Monroe counties.

The Parthenon is the independent student newspaper of Marshall University based in Huntington, West Virginia. The paper began publication in 1898. It currently is published in print on Tuesdays with content added daily online. It is distributed for "free" on the Huntington and South Charleston campuses. The Parthenon is also published online. Student reporters change every semester and are instructed by the faculty adviser in a beat reporting class within the school of journalism. Editors, staff reporters and other staff change annually or every semester.

The Quad-City Times is a daily morning newspaper based in Davenport, Iowa, and circulated throughout the Quad Cities metropolitan area, including Davenport, Bettendorf and Scott County in Iowa; and Moline, East Moline, Rock Island, and Rock Island County in Illinois.

The Patriot-News is the largest newspaper serving the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, metropolitan area. In 2005, the newspaper was ranked in the top 100 in daily and Sunday circulation in the United States. It has been owned by Advance Publications since 1947.

Leonard "Len" Downie Jr. is an American journalist who was executive editor of The Washington Post from 1991 to 2008. He worked in the Post newsroom for 44 years. His roles at the newspaper included executive editor, managing editor, national editor, London correspondent, assistant managing editor for metropolitan news, deputy metropolitan editor, and investigative and local reporter. Downie became executive editor upon the retirement of Ben Bradlee. During Downie's tenure as executive editor, the Washington Post won 25 Pulitzer Prizes, more than any other newspaper had won during the term of a single executive editor. Downie currently serves as vice president at large at the Washington Post, as Weil Family Professor of Journalism at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, and as a member of several advisory boards associated with journalism and public affairs.

The Diamondback is an independent student newspaper associated with the University of Maryland, College Park. It began in 1910 as The Triangle and became known as The Diamondback in 1921. The Diamondback was initially published as a daily print newspaper on weekdays until becoming a weekly online journal in 2013. It is published by Maryland Media, Inc., a non-profit organization. The newspaper receives no university funding and derives its revenue from advertising.

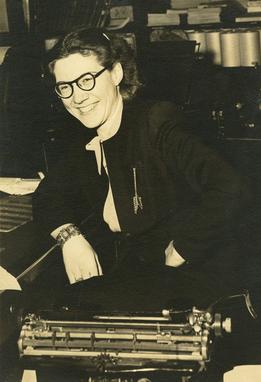

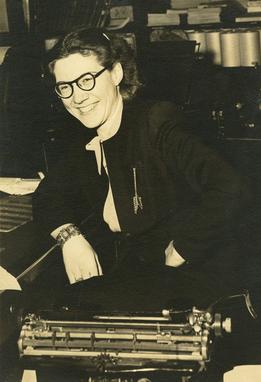

Carol Sutton was an American journalist. She got her journalism degree from the University of Missouri. In 1974 she became the first female managing editor of a major U.S. daily newspaper, The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky. She was cited as the example of female achievement in journalism when Time named American Women as the 1975 People of the Year. During her tenure at the paper, it was awarded the 1971 Penney-Missouri Award for General Excellence and in 1976 the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for its coverage of school desegregation in Louisville. She is also credited with significantly raising the number of minority reporters on staff.

Women in journalism are individuals who participate in journalism. As journalism became a profession, women were restricted by custom from access to journalism occupations, and faced significant discrimination within the profession. Nevertheless, women operated as editors, reporters, sports analysts and journalists even before the 1890s in some countries as far back as the 18th-century.

In journalism, the society page of a newspaper is largely or entirely devoted to the social and cultural events and gossip of the location covered. Other features that frequently appear on the society page are a calendar of charity events and pictures of locally, nationally and internationally famous people. Society pages expanded to become women's page sections.

Vivian Anderson Castleberry was an American newspaper editor, journalist, and women's rights activist, who was elected to the Texas Women's Hall of Fame in 1984.

Marjorie Irene Evers "Marj" Heyduck (1913–1969) was a reporter, columnist and editor for the Dayton Herald, Dayton Press, Dayton Journal, Dayton Journal-Herald, and Dayton Daily News from 1936 to 1969. She also hosted a radio show from 1939 to 1941.

The Missouri Lifestyle Journalism Awards were first awarded in 1960 as the Penney-Missouri Awards to recognize women's pages that covered topics other than society, club, and fashion news, and that also covered such topics as lifestyle and consumer affairs. The Penney-Missouri Awards were often described as the "Pulitzer Prize of feature writing". They were the only nationwide recognition specifically for women's page journalists, at a time when few women had other opportunities to write or edit for newspapers. The annual awards appear to have been last given in 2008.

Marie Willard Anderson was a Miami, Florida newspaper editor. Under her leadership in the 1960s the Miami Herald Women's Page transformed into a nationally recognized progressive women's section, one of the first in the country to do so, and won the Penney-Missouri Award four times.

Dorothy Misener Jurney was an American journalist. As women's page editor for the Miami Herald, she shifted the focus of those pages from the "Four F's – family, food, fashion, and furnishings" – to focus on covering women's issues as hard news, and influenced other newspapers to follow suit. The National Press Club Foundation called her "the godmother of women's pages".

Marjorie Paxson was an American newspaper journalist, editor, and publisher during an era in American history when the women's liberation movement was setting milestones by tackling the barriers of discrimination in the media workplace. Paxson graduated from the University of Missouri School of Journalism in 1944, and began her newspaper career in Nebraska during World War II, covering hard news for wire services. In the 1960s, Paxson worked as assistant editor under Marie Anderson for the women's page of the Miami Herald which, in the 1950s, was considered one of the top women's sections in the United States. From 1963 to 1967, she was president of Theta Sigma Phi, a sorority that evolved into the Association for Women in Communications (AWC). She won the organization's Lifetime Achievement Award and was inducted into its hall of fame. In 1969, she earned a Penney-Missouri award for her work as editor of the women's page in the St. Petersburg Times.

Ruth Ellen (Lovrien) Church was an American food and wine journalist and book author. She spent 38 years as the Chicago Tribune’s food editor and became the first person to write a wine column for a major U.S. paper in 1962, a decade before Frank Prial's column for the New York Times.

Margaret Ann Savoy Pitts Bellows was an American newspaper editor. She was the women's editor for the Phoenix Gazette between 1947 and 1959, and then spent five years at The Arizona Republic. She moved to New York City in 1964 following her third marriage, to fellow journalist Jim Bellows, and wrote for the Associated Press, before joining United Press International to write on its urban beat. After moving to Los Angeles in 1967, she became the women's editor for the Los Angeles Times, writing for Section IV until it was renamed as the View in July 1970, where she profiled women including Joan Didion, Maya Angelou and Nancy Reagan.

Dorothy Roe Lewis was an American newspaper editor and journalist. She was a syndicated columnist and the women's editor for the Associated Press for nineteen years.

Jeanne Voltz was an American food journalist, editor, and cookbook author. She was food editor for the Miami Herald and the Los Angeles Times, two of the most influential food sections in the country during her tenure in the 1950s and 1960s. She won three James Beard awards for her cookbooks.