Related Research Articles

Unemployment, according to the OECD, is the proportion of people above a specified age not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the reference period.

In economics, a discouraged worker is a person of legal employment age who is not actively seeking employment or who has not found employment after long-term unemployment, but who would prefer to be working. This is usually because an individual has given up looking, hence the term "discouraged".

The labor force is the actual number of people available for work and is the sum of the employed and the unemployed. The U.S. labor force reached a record high of 168.7 million civilians in September 2024. In February 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, there were 164.6 million civilians in the labor force. Before the pandemic, the U.S. labor force had risen each year since 1960 with the exception of the period following the Great Recession, when it remained below 2008 levels from 2009 to 2011. In 2021, The Great Resignation resulted in record numbers in voluntary turnover for American workers.

In macroeconomics, the workforce or labour force is the sum of those either working or looking for work :

Babysitting is temporarily caring for a child. Babysitting can be a paid job for all ages; however, it is best known as a temporary activity for early teenagers who are not yet eligible for employment in the general economy. It provides autonomy from parental control and dispensable income, as well as an introduction to the techniques of childcare. It emerged as a social role for teenagers in the 1920s, and became especially important in suburban America in the 1950s and 1960s, when small children were abundant. It stimulated an outpouring of folk culture in the form of urban legends, pulp novels, and horror films.

A pink-collar worker is someone working in the care-oriented career field or in fields historically considered to be women's work. This may include jobs in the beauty industry, nursing, social work, teaching, secretarial work, or child care. While these jobs may also be filled by men, they have historically been female-dominated and may pay significantly less than white-collar or blue-collar jobs.

The United States Women's Bureau (WB) is an agency of the United States government within the United States Department of Labor. The Women's Bureau works to create parity for women in the labor force by conducting research and policy analysis, to inform and promote policy change, and to increase public awareness and education.

In mainstream economic theories, the labour supply is the total hours that workers wish to work at a given real wage rate. It is frequently represented graphically by a labour supply curve, which shows hypothetical wage rates plotted vertically and the amount of labour that an individual or group of individuals is willing to supply at that wage rate plotted horizontally. There are three distinct aspects to labor supply or expected hours of work: the fraction of the population who are employed, the average number of hours worked by those that are employed, and the average number of hours worked in the population as a whole.

The labor force in Japan numbered 65.9 million people in 2010, which was 59.6% of the population of 15 years old and older, and amongst them, 62.57 million people were employed, whereas 3.34 million people were unemployed which made the unemployment rate 5.1%. The structure of Japan's labor market experienced gradual change in the late 1980s and continued this trend throughout the 1990s. The structure of the labor market is affected by: 1) shrinking population, 2) replacement of postwar baby boom generation, 3) increasing numbers of women in the labor force, and 4) workers' rising education level. Also, an increase in the number of foreign nationals in the labor force is foreseen.

A double burden is the workload of people who work to earn money, but who are also responsible for significant amounts of unpaid domestic labor. This phenomenon is also known as the Second Shift as in Arlie Hochschild's book of the same name. In couples where both partners have paid jobs, women often spend significantly more time than men on household chores and caring work, such as childrearing or caring for sick family members. This outcome is determined in large part by traditional gender roles that have been accepted by society over time. Labor market constraints also play a role in determining who does the bulk of unpaid work.

Employment-to-population ratio, also called the employment rate, is a statistical ratio that measures the proportion of a country's working age population that is employed. This includes people that have stopped looking for work. The International Labour Organization states that a person is considered employed if they have worked at least 1 hour in "gainful" employment in the most recent week.

Since the Industrial Revolution, participation of women in the workforce outside the home has increased in industrialized nations, with particularly large growth seen in the 20th century. Largely seen as a boon for industrial society, women in the workforce contribute to a higher national economic output as measure in GDP as well as decreasing labor costs by increasing the labor supply in a society.

The high school movement is a term used in educational history literature to describe the era from 1910 to 1940 during which secondary schools as well as secondary school attendance sprouted across the United States. During the early part of the 20th century, American youth entered high schools at a rapid rate, mainly due to the building of new schools, and acquired skills "for life" rather than "for college." In 1910 18% of 15- to 18-year-olds were enrolled in a high school; barely 9% of all American 18-year-olds graduated. By 1940, 73% of American youths were enrolled in high school and the median American youth had a high school diploma. The movement began in New England but quickly spread to the western states. According to Claudia Goldin, the states that led in the U.S. high school movement had a cohesive, homogeneous population and were more affluent, with a broad middle-class group.

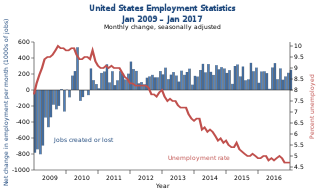

Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes and measures of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

The added worker effect refers to an increase in the labor supply of married women when their husbands become unemployed. Underlying the theory is the assumption that married women are secondary workers with a less permanent attachment to the labor market than their partners. As statistics show, married women do not always behave as secondary workers; therefore, the effect is not a universal phenomenon.

According to Marxist–Leninist theory, the Soviet working class was supposed to be the Soviet Union's ruling class during its transition from the socialist stage of development to full communism. According to Andy Blunden, its influence over production and policies diminished as the Soviet Union's existence progressed.

The gender pay gap or gender wage gap is the average difference between the remuneration for men and women who are employed. Women are generally found to be paid less than men. There are two distinct measurements of the pay gap: non-adjusted versus adjusted pay gap. The latter typically takes into account differences in hours worked, occupations chosen, education and job experience. In other words, the adjusted values represent how much women and men make for the same work, while the non-adjusted values represent how much the average man and woman make in total. In the United States, for example, the non-adjusted average woman's annual salary is 79–83% of the average man's salary, compared to 95–99% for the adjusted average salary. The reasons for the gap link to legal, social and economic factors. These include having children, parental leave, gender discrimination and gender norms. Additionally, the consequences of the gender pay gap surpass individual grievances, leading to reduced economic output, lower pensions for women, and fewer learning opportunities.

American women of Spanish and Latin American descent, also known as Latinas, contributed to United States' efforts in World War II both overseas and on the homefront.

Family policy in the country of Japan refers to government measures that attempt to increase the national birthrate in order to address Japan's declining population. It is speculated that leading causes of Japan's declining birthrate include the institutional and social challenges Japanese women face when expected to care for children while simultaneously working the long hours expected of Japanese workers. Japanese family policy measures therefore seek to make childcare easier for new parents.

Women in the workforce in Francoist Spain faced high levels of discrimination. The end of the Spanish Civil War saw a return of traditional gender roles in the country. These were enforced by the regime through laws that regulated women's labor outside the home and the return of the Civil Code of 1889 and the former Law Procedure Criminal, which treated women as legally inferior to men. During the 1940s, women faced many obstacles to entering the workforce, including financial penalties for working outside the home, job loss upon marriage and few legally available occupations.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goldin, Claudia; Claudia Olivetti (2013). "Shocking labor supply: A reassessment of the role of World War II on US women's labor supply". National Bureau of Economic Research. w18676.

- 1 2 3 Goldin, Claudia (2006). "The quiet revolution that transformed women's employment, education, and family". National Bureau of Economic Research. w11953.

- 1 2 "Women in the WorkForce during World War II". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McDermott, Annette. "How World War II Empowered Women". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- 1 2 3 Moody, Kim (1988). An Injury to All: The Decline of American Unionism. London: Verso. p. 22. ISBN 0860919293.

- ↑ Rupp, Leila (1978). Mobilizing women for war: German and American propaganda, 1939-1945 . Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691046492.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "American Women in World War II". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schweitzer, Mary M. (1980). "World War II and Female Labor Force Participation Rates". The Journal of Economic History. 40 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1017/S0022050700104577. JSTOR 2120427.

- ↑ Anderson, Karen Tucker (1982). "Last hired, first fired: Black women workers during World War II". The Journal of American History. 69 (1): 82–97. doi:10.2307/1887753. JSTOR 1887753.

- ↑ Chafe, William H. (1972). The American Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic, and Political Roles. 1920-1970. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195015789.

- 1 2 Goldin, Claudia (1991). "The role of World War II in the rise of women's work". National Bureau of Economic Research. w3203.

- ↑ Palmer, Gladys Louise; Carol Brainerd (1954). Labor mobility in six cities: a report on the survey of patterns and factors in labor mobility, 1940-1950. Social Science Research Council.

- ↑ Stansell, Christine (2011). The feminist promise : 1792 to the present (Modern Library paperback ed.). New York: Modern Library. p. 184. ISBN 978-0812972023.

- ↑ Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Census. 1975. p. 132. ISBN 0160004608.