Feminist economics is the critical study of economics and economies, with a focus on gender-aware and inclusive economic inquiry and policy analysis. Feminist economic researchers include academics, activists, policy theorists, and practitioners. Much feminist economic research focuses on topics that have been neglected in the field, such as care work, intimate partner violence, or on economic theories which could be improved through better incorporation of gendered effects and interactions, such as between paid and unpaid sectors of economies. Other feminist scholars have engaged in new forms of data collection and measurement such as the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), and more gender-aware theories such as the capabilities approach. Feminist economics is oriented towards the goal of "enhancing the well-being of children, women, and men in local, national, and transnational communities."

Parental leave, or family leave, is an employee benefit available in almost all countries. The term "parental leave" may include maternity, paternity, and adoption leave; or may be used distinctively from "maternity leave" and "paternity leave" to describe separate family leave available to either parent to care for small children. In some countries and jurisdictions, "family leave" also includes leave provided to care for ill family members. Often, the minimum benefits and eligibility requirements are stipulated by law.

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property. According to Marxist feminists, women's liberation can only be achieved by dismantling the capitalist systems in which they contend much of women's labor is uncompensated. Marxist feminists extend traditional Marxist analysis by applying it to unpaid domestic labor and sex relations.

Feminization of poverty refers to a trend of increasing inequality in living standards between men and women due to the widening gender gap in poverty. This phenomenon largely links to how women and children are disproportionately represented within the lower socioeconomic status community in comparison to men within the same socioeconomic status. Causes of the feminization of poverty include the structure of family and household, employment, sexual violence, education, climate change, "femonomics" and health. The traditional stereotypes of women remain embedded in many cultures restricting income opportunities and community involvement for many women. Matched with a low foundation income, this can manifest to a cycle of poverty and thus an inter-generational issue.

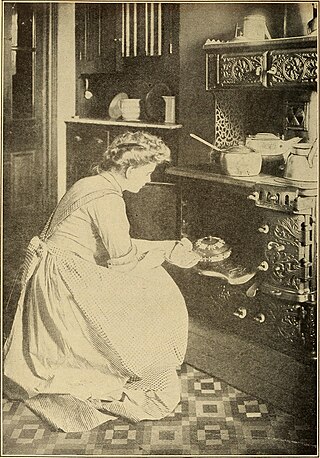

A double burden is the workload of people who work to earn money, but who are also responsible for significant amounts of unpaid domestic labor. This phenomenon is also known as the Second Shift as in Arlie Hochschild's book of the same name. In couples where both partners have paid jobs, women often spend significantly more time than men on household chores and caring work, such as childrearing or caring for sick family members. This outcome is determined in large part by traditional gender roles that have been accepted by society over time. Labor market constraints also play a role in determining who does the bulk of unpaid work.

The capability approach is a normative approach to human welfare that concentrates on the actual capability of persons to achieve lives they value rather than solely having a right or freedom to do so. It was conceived in the 1980s as an alternative approach to welfare economics.

Bina Agarwal is an Indian development economist and Professor of Development Economics and Environment at the Global Development Institute at The University of Manchester. She has written extensively on land, livelihoods and property rights; environment and development; the political economy of gender; poverty and inequality; legal change; and agriculture and technological transformation.

Unpaid labor or unpaid work is defined as labor or work that does not receive any direct remuneration. This is a form of non-market work which can fall into one of two categories: (1) unpaid work that is placed within the production boundary of the System of National Accounts (SNA), such as gross domestic product (GDP); and (2) unpaid work that falls outside of the production boundary, such as domestic labor that occurs inside households for their consumption. Unpaid labor is visible in many forms and isn't limited to activities within a household. Other types of unpaid labor activities include volunteering as a form of charity work and interning as a form of unpaid employment. In a lot of countries, unpaid domestic work in the household is typically performed by women, due to gender inequality and gender norms, which can result in high-stress levels in women attempting to balance unpaid work and paid employment. In poorer countries, this work is sometimes performed by children.

Care work is a sub-category of work that includes all tasks that directly involve the care processes done in service of others. It is often differentiated from other forms of work because it is considered to be intrinsically motivated. This perspective defines care labor as labor done out of affection or a sense of responsibility for other people, with no expectation of immediate pecuniary reward. Regardless of motivation, care work includes care activities done for pay as well as those done without remuneration.

If Women Counted (1988) is a book by New Zealand academic and former politician Marilyn Waring, that is regarded as the "founding document" of the discipline of feminist economics. The book is a groundbreaking and systematic critique of the system of national accounts, the international standard of measuring economic growth, and the ways in which women's unpaid work as well as the value of Nature have been excluded from what counts as productive in the economy.

Gender and development is an interdisciplinary field of research and applied study that implements a feminist approach to understanding and addressing the disparate impact that economic development and globalization have on people based upon their location, gender, class background, and other socio-political identities. A strictly economic approach to development views a country's development in quantitative terms such as job creation, inflation control, and high employment – all of which aim to improve the ‘economic wellbeing’ of a country and the subsequent quality of life for its people. In terms of economic development, quality of life is defined as access to necessary rights and resources including but not limited to quality education, medical facilities, affordable housing, clean environments, and low crime rate. Gender and development considers many of these same factors; however, gender and development emphasizes efforts towards understanding how multifaceted these issues are in the entangled context of culture, government, and globalization. Accounting for this need, gender and development implements ethnographic research, research that studies a specific culture or group of people by physically immersing the researcher into the environment and daily routine of those being studied, in order to comprehensively understand how development policy and practices affect the everyday life of targeted groups or areas.

Ailsa McKay was a Scottish economist, government policy adviser, a leading feminist economist and Professor of Economics at Glasgow Caledonian University.

Gender inequality both leads to and is a result of food insecurity. According to estimates, women and girls make up 60% of the world's chronically hungry and little progress has been made in ensuring the equal right to food for women enshrined in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Women face discrimination both in education and employment opportunities and within the household, where their bargaining power is lower. On the other hand, gender equality is described as instrumental to ending malnutrition and hunger. Women tend to be responsible for food preparation and childcare within the family and are more likely to be spent their income on food and their children's needs. The gendered aspects of food security are visible along the four pillars of food security: availability, access, utilization and stability, as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization.

Women in Ecuador are generally responsible for the upbringing and care of children and families; traditionally, men have not taken an active role. Ever more women have been joining the workforce, which has resulted in men doing some housework, and becoming more involved in the care of their children. This change has been greatly influenced by Eloy Alfaro's liberal revolution in 1906, in which Ecuadorian women were granted the right to work. Women's suffrage was granted in 1929.

Gender inequality in Mexico refers to disparate freedoms in health, education, and economic and political abilities between men and women in Mexico. It has been diminishing throughout history, but continues to persist in many forms including the disparity in women's political representation and participation, the gender pay gap, and high rates of domestic violence and femicide. As of 2022, the World Economic Forum ranks Mexico 31st in terms of gender equality out of 146 countries. Structural gender inequality is relatively homogeneous between the Mexican states as there are very few regional differences in the inequalities present.

Naila Kabeer is an Indian-born British Bangladeshi social economist, research fellow, writer and Professor at the London School of Economics. She was also president of the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) from 2018 to 2019. She is on the editorial committee of journals such as Feminist Economist, Development and Change, Gender and Development, Third World Quarterly and the Canadian Journal of Development Studies. She works primarily on poverty, gender and social policy issues. Her research interests include gender, poverty, social exclusion, labour markets and livelihoods, social protection, focused on South and South East Asia.

Stephanie Seguino is a feminist professor of economics at the University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont, United States. She was the president of the International Association for Feminist Economics from 2010 to 2011 and has also carried out research for both the United Nations and the World Bank.

Yana van der Meulen Rodgers is a professor in the Department of Labor Studies and Employment Relations in the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers University,. She also serves as Faculty Director of the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers.

Reproductive labor or work is often associated with care giving and domestic housework roles including cleaning, cooking, child care, and the unpaid domestic labor force. The term has taken on a role in feminist philosophy and discourse as a way of calling attention to how women in particular are assigned to the domestic sphere, where the labor is reproductive and thus uncompensated and unrecognized in a capitalist system. These theories have evolved as a parallel of histories focusing on the entrance of women into the labor force in the 1970s, providing an intersectionalist approach that recognizes that women have been a part of the labor force since before their incorporation into mainstream industry if reproductive labor is considered.

Shahra Razavi is an Iranian-born academic and senior United Nations official specialising in gender and social development. A graduate of the London School of Economics and Oxford University, Razavi is currently Director of the Social Protection Department of the International Labour Organisation in Geneva, Switzerland.