Military theory

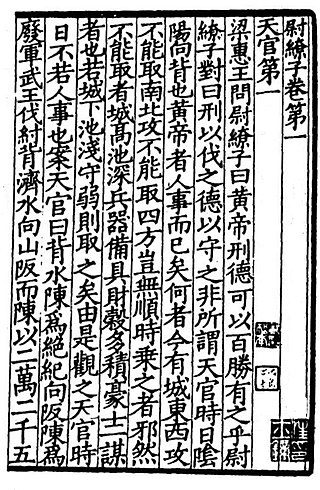

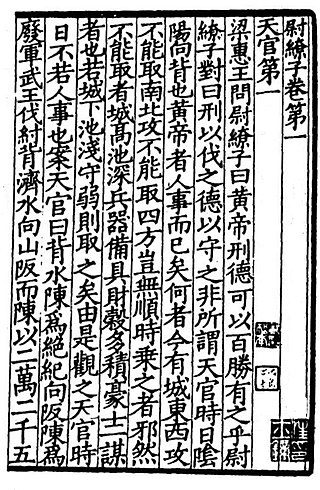

The present text of the Wuzi consists of six sections, each focusing on a critical aspect of military affairs: Planning for the State; Evaluating the Enemy; Controlling the Army; the Tao of the General; Responding to Change; and, Stimulating the Officers. Although each chapter is less concentrated than the traditional topic headings would suggest, they depict the subject matter and general scope of the book as a whole. [2]

As a young man, Wu Qi spent a formative three years as a student of Confucianism. After gaining several years of administrative experience, he came to believe that, in order for benevolence and righteousness to survive in his time, military strength and preparation were necessary. Without a strong military to defend the just, he believed that Confucian virtues would disappear, and evil would dominate the world. Because of his emphasis on the importance of the military for safeguarding civil rights and liberty, the author of the Wuzi states that commanders must be selected carefully, ideally from those possessing courage and who excelled in military arts, but who also possessed good civil administration skills, and who displayed Confucian virtues, particularly those of wisdom and self-control. [3]

Because armies in the Warring States were heavily dependent on the horse, both for transportation and for the power of the chariot, the Wuzi places a greater importance and focus on raising and maintaining a force of cavalry more than on maintaining infantry in its discussions of logistics. Because of the shift away from warfare fought among nobility, towards the mass mobilization of civilian armies, the Wuzi stresses the importance of gaining the strong support and loyalty of the common people. Because of its focus on the importance of civil administration as a necessary aid to military strength, the Wuzi stresses the implementation of Confucian policies designed to improve the material welfare of the people, gain their emotional support, and support their moral virtues. [4]

Harmony and organization are equally important to each other: without harmony, an organization will not be cohesive; but, without organization, harmony will not be effective in achieving collective goals. There are three steps to achieving a disciplined, effective fighting force: proper organization; extensive training; and, thorough motivation. It is only after the creation of a disciplined, cohesive army that achieving victory becomes a matter of tactics and strategy. Much of the Wuzi discusses the means to achieve such a force. [5]

Regarding the Legalist theories of achieving desired action through the proper exercise of reward and punishment, the Wuzi states that rewards and punishments are, by themselves, insufficient: excessive reward may cause individuals to pursue profit and glory at the expense of the group, while excessive punishment can lower morale, in the worst cases forcing men to flee service rather than face the consequences of failure. In addition to reward and punishment, the general should inculcate (essentially pseudo-Confucian) values into his soldiers: men fighting for what they believe is a moral cause will prefer death to living ignominiously, improving the chances of success for both the individual soldier and the army as a whole. It is only with the combination of both moral focus and effective rewards and punishments that the army will become a disciplined, spirited, strongly motivated force. [6]

The Wuzi advises generals to adopt different tactics and strategy based on their assessment of battlefield situations. Factors affecting appropriate tactics and strategy include: the relative terrain and weather of the engagement; the national character of the combatants; the enemy commander's personal history and characteristics; and, the relative morale, discipline, fatigue, number, and general quality of both friendly and enemy forces. In gathering this information, and in preventing the enemy from gaining it, espionage and deception are paramount. [7]

Authorship

Because of the lack of archaeological evidence, there is no consensus among modern scholars concerning the date that The Wuzi was composed, and/or last modified. A work known as Wuzi was one of the most widely referenced books on military strategy among the records that existed in the Warring States period. (Notable contemporary records mentioning the Wuzi are the Spring and Autumn Annals and the Han Feizi .) Sima Qian, in his Shiji , equates the popularity of the Wuzi, in both the Warring States and the Han dynasty, with that of Sun Tzu's Art of War. [8] There is evidence that, in the Warring States, two different texts titled "Wuzi" existed, but (at least) one of them has been lost. The fact that large portions of the text seem to have been either lost or deliberately excised from surviving editions makes the dating of the work more challenging. [9] There is evidence both supporting the theory that much of the present text was authored in the mid-Warring States, and that it was modified after this date.

The most systematic study of the Wuzi's date of composition and authorship, based on historical references and the book's content, concludes that the core of the work was likely authored by Wu Qi himself, but was likely subject to serious losses of content, revisions, and accretions after his lifetime. This theory assumes that Wu Qi's disciples initially continued amending the text, but cannot account for some content that seems to have been inserted as late as the Han dynasty (possibly in an effort to "update" the work). [10] The following five points summarize this study's conclusions regarding the Wuzi's date of composition.

Historical references

The writings of Wu Qi were known to be in wide circulation by the late Warring States period. The assertion of the book's early popularity is based on the comment, from the Han Feizi , that "Within the borders everyone speaks about warfare, and everywhere households secretly store away the books of Sun and Wu." The Shiji corroborates this information. The Wuzi continued to be studied both by famous Han dynasty figures, and by those in the Three Kingdoms period. The record of continuous attention supports the view that was continuously transmitted from the Warring States until at least the Three Kingdoms period. [11]

Shared passages between contemporary works

The Wuzi shares both concepts and whole passages with other works dated more conclusively to the Warring States period. (The texts with which the Wuzi shares the greatest resemblance are the Wei Liaozi , Sun Bin's Art of War, and the Six Secret Teachings .) The close similarities that the Wuzi shares with other works from the Warring States period suggest that the Wuzi predates these other works, largely because Sun Bin's Art of War had been lost for two thousand years, so passages from Sun Bin's work could not have been lifted to forge the Wuzi (just prior to the Tang dynasty, as was claimed in later Chinese history.) [12]

Perspective / occupation of writer

Wu Qi was both a civil and military leader, and excelled in both occupations. This dual role was common until the early Warring States period, but disappeared in later Chinese history. The fact that the Wuzi was written from the perspective of an official with both civil and martial responsibilities supports the theory that it dates from the early Warring States. [13]

Archaeological support

Qing scholastic criticism discounted the possible authenticity of the text based on its mention of military practices then considered anachronous to the Warring States period. The list of items (then) considered anachronous includes: playing pipes in camp; the inclusion of terms not otherwise known to have been invented until after the Warring States; and, the appearance of certain astrological banners used by different units. Because recent archeological discoveries have confirmed that all of these "anachronous" practices existed by the Warring States, this Qing-era evidence for the Wuzi's forgery is not valid. [14]

Remaining criticisms

Remaining criticisms which the defenders of the Wuzi's authenticity cannot account for center on the book's description of cavalry as a major, important branch of the military. Because the use of cavalry (presumably) did not become important until the (very) late-Warring States period, the text's emphasis on cavalry implies that present editions must have been edited after Wu Qi's death (unless cavalry became important in central China much earlier than presently believed). Unless evidence is found that cavalry became important in China before c. 300 BC (the date modern scholars generally assume Cavalry became important), then either parts of the Wuzi, or the entire text, must be attributed either to the late Warring States or the early Han dynasty.

Modern scholars conclude that the most satisfying conclusion, accounting for the above facts, is that the text was substantially created by "Wu Qi himself, but that in the course of transmission and revision, later Warring States strategists (and probably Han students)... added passages on cavalry and otherwise emended some of the terminology." [15] By being a work which was the product of a famous historical figure, but amended by future generations of strategists, the Wuzi's composition is very similar to most of the other Seven Military Classics.

The Chinese classics or canonical texts are the works of Chinese literature authored prior to the establishment of the imperial Qin dynasty in 221 BC. Prominent examples include the Four Books and Five Classics in the Neo-Confucian tradition, themselves an abridgment of the Thirteen Classics. The Chinese classics used a form of written Chinese consciously imitated by later authors, now known as Classical Chinese. A common Chinese word for "classic" literally means 'warp thread', in reference to the techniques by which works of this period were bound into volumes.

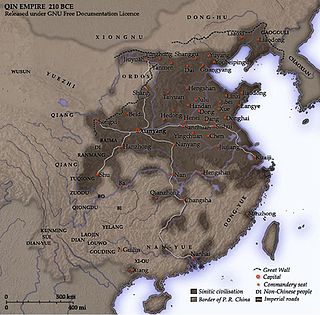

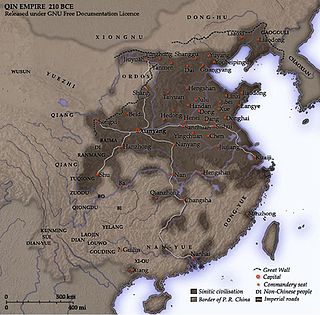

The Qin dynasty was the first dynasty of Imperial China. It is named for its progenitor state of Qin, which was a fief of the confederal Zhou dynasty which had endured for over five centuries—until 221 BC, when it assumed an imperial prerogative following its complete conquest of its rival states, a state of affairs that lasted until its collapse in 206 BC. It was formally established after the conquests in 221 BC, when Ying Zheng, who had become king of the Qin state in 246, declared himself to be "Shi Huangdi", the first emperor.

Sun Tzu was a Chinese military general, strategist, philosopher, and writer who lived during the Eastern Zhou period. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of The Art of War, an influential work of military strategy that has affected both Western and East Asian philosophy and military thought. Sun Tzu is revered in Chinese and East Asian culture as a legendary historical and military figure. His birth name was Sun Wu and he was known outside of his family by his courtesy name Changqing. The name Sun Tzu—by which he is more popularly known—is an honorific which means "Master Sun".

The Warring States period in Chinese history comprises the final centuries of the Zhou dynasty, which were characterized by warfare, bureaucratic and military reform, and political consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the wars of conquest that saw the state of Qin annex each of the other contender states by 221 BC and found the Qin dynasty, the first imperial dynastic state in East Asian history.

Han was an ancient Chinese state during the Warring States period of ancient China. Scholars frequently render the name as Hann to clearly distinguish it from China's later Han dynasty.

The Analects, also known as the Sayings of Confucius, is an ancient Chinese philosophical text composed of sayings and ideas attributed to Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled by his followers. The consensus among scholars is that large portions of the text were composed during the Warring States period (475–221 BC), and that the work achieved its final form during the mid-Han dynasty. During the early Han, the Analects was merely considered to be a commentary on the Five Classics. However, by the dynasty's end the status of the Analects had grown to being among the central texts of Confucianism.

Zhao was one of the seven major states during the Warring States period of ancient China. It emerged from the tripartite division of Jin, along with Han and Wei, in the 5th century BC. Zhao gained considerable strength from the military reforms initiated during the reign of King Wuling, but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Qin at the Battle of Changping. Its territory included areas in the modern provinces of Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Shanxi and Shaanxi. It bordered the states of Qin, Wei, and Yan, as well as various nomadic peoples including the Hu and Xiongnu. Its capital was Handan, in modern Hebei province.

Qin was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty. It is traditionally dated to 897 BC. The Qin state originated from a reconquest of western lands that had previously been lost to the Xirong. Its location at the western edge of Chinese civilisation allowed for expansion and development that was not available to its rivals in the North China Plain.

The Classic of Poetry, also Shijing or Shih-ching, translated variously as the Book of Songs, Book of Odes, or simply known as the Odes or Poetry, is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, comprising 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BC. It is one of the "Five Classics" traditionally said to have been compiled by Confucius, and has been studied and memorized by scholars in China and neighboring countries over two millennia. It is also a rich source of chengyu that are still a part of learned discourse and even everyday language in modern Chinese. Since the Qing dynasty, its rhyme patterns have also been analysed in the study of Old Chinese phonology.

Jiang Ziya, also known by several other names, was a Chinese military general, monarch, strategist, and writer who helped kings Wen and Wu of Zhou overthrow the Shang in ancient China. Following their victory at Muye, he continued to serve as a Zhou minister. He remained loyal to the regent Duke of Zhou during the Rebellion of the Three Guards; following the Duke's punitive raids against the restive Eastern Barbarians or Dongyi, Jiang was enfeoffed with their territory as the marchland of Qi. He established his seat at Yingqiu. He is also celebrated as one of the main heroes in the Fengshen Bang.

The Four Books and Five Classics are authoritative and important books associated with Confucianism, written before 300 BC. They are traditionally believed to have been either written, edited or commented by Confucius or one of his disciples. Starting in the Han dynasty, they became the core of the Chinese classics on which students were tested in the Imperial examination system.

The Seven Military Classics were seven important military texts of ancient China, which also included Sun-tzu's The Art of War. The texts were canonized under this name during the 11th century AD, and from the time of the Song dynasty, were included in most military leishu. For imperial officers, either some or all of the works were required reading to merit promotion, like the requirement for all bureaucrats to learn and know the work of Confucius. The Art of War was translated into Tangut with commentary.

The Six Secret Teachings, is a treatise on civil and military strategy traditionally attributed to Lü Shang, a top general of King Wen of Zhou, founder of the Zhou dynasty, at around the eleventh century BC. Modern historians nominally date its final composition to the Warring States period, but some scholars believe that it preserves at least vestiges of ancient Qi political and military thought. Because it is written from the perspective of a statesman attempting to overthrow the ruling Shang dynasty, it is the only one of the Seven Military Classics explicitly written from a revolutionary perspective.

The Methods of the Sima is a text discussing laws, regulations, government policies, military organization, military administration, discipline, basic values, tactics, and strategy. It is considered to be one of the Seven Military Classics of ancient China. It was developed in the state of Qi during the 4th century BC, in the mid-Warring States period.

Questions and Replies between Emperor Taizong of Tang and Li Weigong is a fictional dialogue between Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty and Li Jing, a prominent Tang general. It discusses matters of military strategy, and is considered to be one of the Seven Military Classics of China.

The Wei Liaozi is a text on military strategy, one of the Seven Military Classics of ancient China. It was written during the Warring States period.

The Three Strategies of Huang Shigong is a treatise on military strategy that was historically associated with the Taoist hermit Huang Shigong and Han dynasty general Zhang Liang. Huang Shigong gave this treatise to Zhang Liang, that allowed Zhang to transform into an adept statesman and powerful war theorist. The treatise's literal name is "the Three Strategies of the Duke of Yellow Rock", based on the traditional account of the book's transmission to Zhang. Modern scholars note the similarity between its philosophy and the philosophy of Huang-Lao Daoism. It is one of China's Seven Military Classics.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient China:

The military of the Warring States refers primarily to the military apparatuses of the Seven Warring States which fought from around 475 BC to 221 BC when the state of Qin conquered the other six states, forming China's first imperial dynasty, the Qin dynasty.