Related Research Articles

Rav Abba bar Aybo, commonly known as Abba Arikha or simply as Rav (רַב), was a Jewish amora of the 3rd century. He was born and lived in Kafri, Asoristan, in the Sasanian Empire.

The Mishnah or the Mishna is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. It is also the first major work of rabbinic literature. The Mishnah was redacted by Judah ha-Nasi probably in Beit Shearim or Sepphoris between the ending of the second century and the beginning of the 3rd century CE in a time when, according to the Talmud, the persecution of Jews and the passage of time raised the possibility that the details of the oral traditions of the Pharisees from the Second Temple period would be forgotten. Most of the Mishnah is written in Mishnaic Hebrew, but some parts are in Aramaic.

Shlomo Yitzchaki, generally known by the acronym Rashi, was a medieval French rabbi, the author of comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible.

The Talmud is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (halakha) and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewish cultural life and was foundational to "all Jewish thought and aspirations", serving also as "the guide for the daily life" of Jews.

Rav Ashi (352–427) was a Babylonian Jewish rabbi, of the sixth generation of amoraim. He reestablished the Academy at Sura and was the first editor of the Babylonian Talmud.

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writing, and thus corresponds with the Hebrew term Sifrut Chazal. This more specific sense of "Rabbinic literature"—referring to the Talmudim, Midrash, and related writings, but hardly ever to later texts—is how the term is generally intended when used in contemporary academic writing. The terms mefareshim and parshanim (commentaries/commentators) almost always refer to later, post-Talmudic writers of rabbinic glosses on Biblical and Talmudic texts.

Jewish ethics is the ethics of the Jewish religion or the Jewish people. A type of normative ethics, Jewish ethics may involve issues in Jewish law as well as non-legal issues, and may involve the convergence of Judaism and the Western philosophical tradition of ethics.

The exilarch was the leader of the Jewish community in Persian Mesopotamia during the era of the Parthians, Sasanians and Abbasid Caliphate up until the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258 CE, with intermittent gaps due to ongoing political developments. The exilarch was regarded by the Jewish community as the royal heir of the House of David and held a place of prominence as both a rabbinical authority and as a noble within the Persian court. Within the Sasanian Empire, the exilarch was the political equivalent of the Catholicos of the Christian Church of the East, and was thus responsible for community-specific organizational tasks such as running the rabbinical courts, collecting taxes from Jewish communities, supervising and providing financing for the Talmudic academies in Babylonia, and the charitable re-distribution and financial assistance to needy members of the exile community. The position of exilarch was hereditary, held in continuity by a family that traced its patrilineal descent from antiquity stemming from king David.

Rav Nachman bar Yaakov was a Jewish Talmudist who lived in Babylonia, known as an Amora of the third generation. He was the husband of Yalta.

Nehardea or Nehardeah was a city from the area called by ancient Jewish sources Babylonia, situated at or near the junction of the Euphrates with the Nahr Malka, one of the earliest and most prominent centers of Babylonian Judaism. It hosted the Nehardea Academy, one of the most prominent Talmudic academies in Babylonia, and was home to great scholars such as Samuel of Nehardea, Rav Nachman, and Amemar.

Yehudai ben Nahman was the head of the yeshiva in Sura from 757 to 761, during the Gaonic period of Judaism. He was originally a member of the academy of Pumbedita, but Exilarch Solomon ben Hisdai appointed him as Gaon of Sura as "there is no one there as distinguished as he is for wisdom".

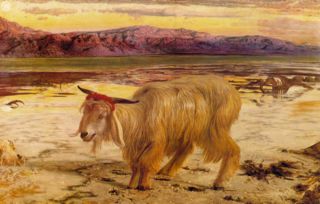

Acharei Mot is the 29th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It is the sixth weekly portion in the Book of Leviticus, containing Leviticus 16:1–18:30. It is named after the fifth and sixth Hebrew words of the parashah, its first distinctive words.

Shabbat is the first tractate of Seder Moed of the Mishnah and of the Talmud. The tractate deals with the laws and practices regarding observing the Jewish Sabbath. The tractate focuses primarily on the categories and types of activities prohibited on the Sabbath according to interpretations of many verses in the Torah, notably Exodus 20:9–10 and Deut. 5:13–14.

Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak was a Babylonian rabbi, of the fourth and fifth generations of amoraim.

Rabbah bar Abuha was a Babylonian rabbi of the second generation of amoraim.

Rav Huna bar Natan (Hebrew: הונא בר נתן, read as Rav Huna bereih deRav Natan was a Babylonian rabbi and exilarch, of the fifth and sixth generations of amoraim.

Pum-Nahara Academy was a Jewish Yeshiva academy in Babylon, during the era of the Jewish Amora sages, in the town of Pum-Nahara, Babylonia, that was within the area of jurisdiction of Sura city, and was situated on the east bank of the "Sura" river, nearby the Sura river's estuary to the Tigris river, and thus it was granted its name. According to the Talmud, the Jewish community in Pum-Nahara city, were poor. The dean of the Yeshiva academy, that was third in the line of importance, out of four Yeshiva academies that existed at the time in Babylonia, was Rav Kahana III, who was the Rabbi teacher of Rav Ashi, and a disciple of Rabbah bar Nahmani ("Rabbah"). Rav Kahana III also resided at Pum-Nahara. One may note some additional Jewish Amora sages that resided and were active at the time at Pum-Nahara, and among them: R. Aha b. Rab, who later became an Exilarch, as well as Rab b. Shaba.

Rabbi Zeira's stringency or the stringency of the daughters of Israel relates to the law of niddah and refers to the stringency expounded in the Talmud where all menstruant women, at the conclusion of their menstrual flow, were to count seven days of cleanness, just as women would do who suffered an "irregular flow" as defined in Jewish law.

Sicaricon, literally "usurping occupant; possessor of confiscated property; the law concerning the purchase of confiscated property", refers in Jewish law to a former act and counter-measure meant to deal effectively with religious persecution against Jews in which the Roman government had permitted its own citizens to seize the property of Jewish landowners who were either absent or killed in war, or taken captive, or else where Roman citizens had received property that had been confiscated by the state in the laws prescribed under ager publicus, and to which the original Jewish owners of such property had not incurred any legal debt or fine, but had simply been the victims of war and the illegal, governmental expropriation of such lands from their rightful owners or heirs. The original Jewish law, made at some time after the First Jewish-Roman War with Vespasian and his son Titus, saw additional amendments by later rabbinic courts, all of which were meant to safe-guard against depriving the original landowners and their heirs of any land that belonged to them, and to ensure their ability to redeem such property in the future.

Ḥanan bar Rava or Ḥanan bar Abba was a Talmudic sage and second-generation Babylonian Amora. He lived in Israel, moved to Babylonia with Abba b. Aybo, and died there ca. 290 CE. He is distinct from the late-generation Babylonian Amora of the same name who apparently conversed with Ashi.

References

- 1 2 Hauptman, Judy. "Yalta." Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. 31 December 1999. Jewish Women's Archive. Accessed December 14, 2022.

- ↑ Labovitz, G. (2013). Rabbis and “Guerrilla Girls” A Bavli Motif of the Female (Counter) Voice in the Rabbinic Legal System. Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal, 10(2).

- ↑ Kosman, A. (2011). A cup of affront and anger: Yaltha as an early feminist in the Talmud. Journal of Textual Reasoning, 6(2), 35-40.

- ↑ Ilan, T. (2022). Women quoting scripture in rabbinic literature. Rabbinic Literature, 4, 45.

- ↑ Hauptman, J. (2010). A new view of women and Torah study in the talmudic period. Jewish Studies, an Internet Journal JSIJ, 9, 249-292.

- ↑ Weingarten, S. (2010). Gynaecophagia: Metaphors of Women as Food in the Talmudic Literature. In Food and Language: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking 2009 (Vol. 28). Oxford Symposium.

- ↑ Fonrobert, C. E. (2015). Yalta’s Ruse. Women and Water: Menstruation in Jewish Life and Law, 60.

- ↑ Cristofar, I. S. (2000). Blood, Water and the Impure Woman: Can Jewish Women Reconcile Between Ancient Law and Modern Feminism. S. Cal. RL & Women's Stud., 10, 451.

- ↑ Rashi on Gittin (67b)